The storm emerges over the eastern Atlantic in late August, first as a slow-moving tropical system that remains largely unnoticed in faraway Texas. It gains power as it drifts westward into warmer Caribbean waters, lashing island coastlines and leaving a trail of destruction in its wake. By the time the storm enters the Gulf of Mexico and churns toward the southeast corner of Texas, it has transformed into a category 4 hurricane with 130-mile-per-hour winds that fan out for 200 miles in every direction.

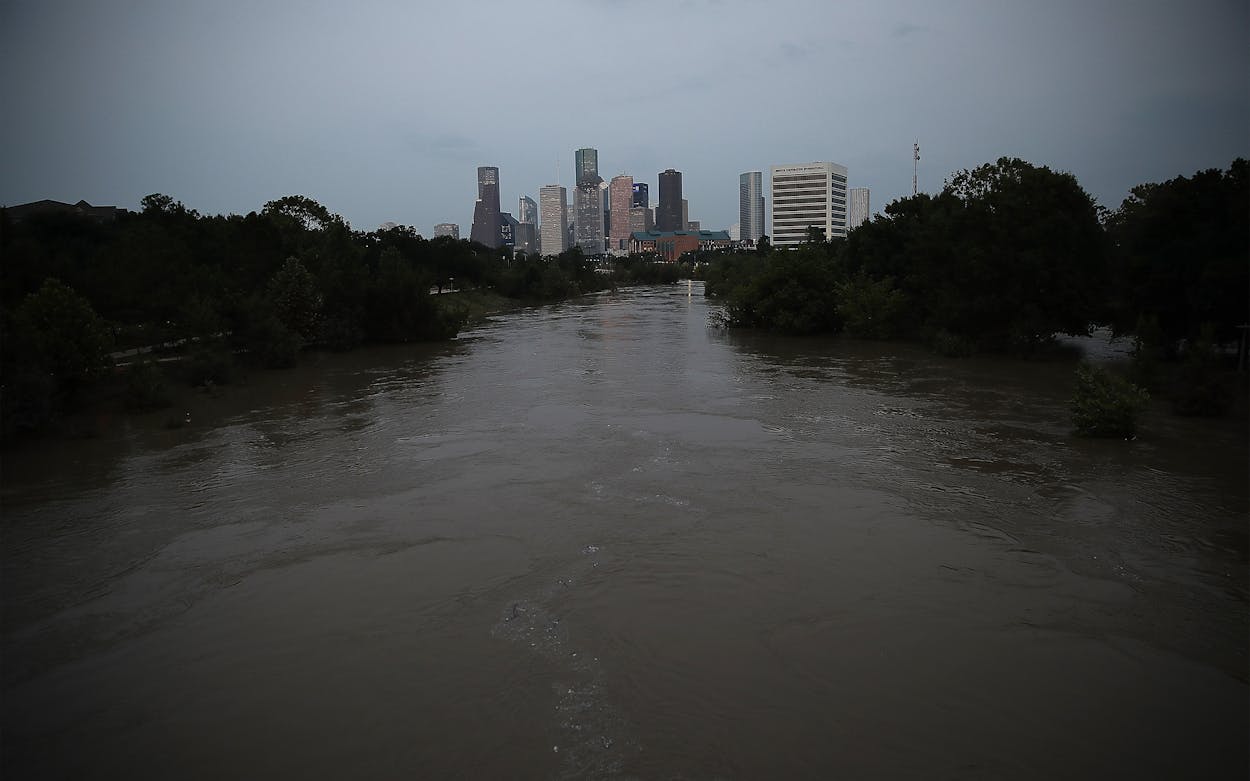

Unlike 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, which made landfall just north of Corpus Christi, the swirling behemoth slams into land some two hundred miles up the coastline near Galveston Island. As the hurricane moves inland, it functions like a giant wall of wind, pushing water north from Galveston Bay—one of the largest estuaries in the United States—into the smaller bays, rivers, and bayous that comprise the Houston Ship Channel, home of the largest petrochemical energy complex in the United States.

This is a hypothetical that Terence O’Rourke, an environmental attorney and hydrology expert with the Harris County Attorney’s Office, has been warning public officials about for the last decade. He says what comes next in the disaster scenario would become “America’s version of Chernobyl”—the Soviet nuclear power plant that melted down in 1986, killing 4,000 people over time and forcing the evacuation of nearly 50,000. The storm O’Rourke predicts could displace hundreds of thousands and create a sprawling contamination zone that stretches across Galveston Bay.

Local hurricane experts agree that a violent storm surge in the channel of at least 26 feet—a reasonable estimate for a category 4 storm that hits Galveston directly—would initially inundate densely populated, low-lying communities on the western half of Galveston Bay. Debris from those communities would then combine with thousands of shipping containers in the area, forming a destructive wall of steel and wood that would slam into thousands of chemical and crude oil storage tanks. Many tanks would be broken open by the battering ram of debris, while others would be ripped from their foundations by the water, releasing their deadly contents. A detailed inventory of hazardous chemicals around the Ship Channel remains difficult to come by, thanks to a Texas law that restricts public disclosure of information that could be utilized by terrorists. However, a 2016 Houston Chronicle investigation of the area’s dangerous chemicals revealed that communities near the Ship Channel live in close proximity to toxic substances, such as silane gas, methyl mercaptan, hydrofluoric acid, sodium sulfide, and ammonia. On at least three occasions, the investigation found, those substances have been released, killing workers and endangering nearby residents. The paper has also catalogued more than one hundred toxic releases during Hurricane Harvey alone, most of them from Houston’s petrochemical corridor.

“There are thousands of chemical tanks and many refineries with products that are so poisonous, so volatile, and so explosive that the result of this could be the greatest environmental disaster in the history of the planet,” O’Rourke said from his home in Houston on a recent afternoon. “Downtown Houston could be flooded with deadly chemicals, entire communities could be displaced, and Galveston Bay would go from the vibrant ecological system that it is to something catastrophic—a giant toxic pond.”

O’Rourke’s predictions are harrowing. Some in the petrochemical industry argue they’re overblown. Hector Rivera, president of the Texas Chemical Council, a trade association of chemical manufacturing facilities in Texas, called O’Rourke’s worry that a powerful storm surge would inevitably result in environmental disaster “fear-mongering.” He said that the petrochemical industry has learned from past weather events and has begun to design facilities to withstand major storms, and now employs private meteorological teams.

The likelihood of a hurricane the size of the one O’Rourke worries about directly hitting the Ship Channel is also difficult to assess. Some experts think there’s a decent chance of such a storm in the near future. In an annual state-by-state forecast, a team of Colorado State University researchers, using statistical modeling and historical data, says there is a 47 percent chance of at least one hurricane making landfall in Texas this year and a 19 percent chance that the storm will be a category 3 or higher. One Rice University study estimates that a hurricane strikes the Houston-Galveston region on average every nine years, and a major hurricane hits every quarter-century—the last being 1983’s Alicia, a category 3 storm, although Ike, a category 2 in 2008, had a surge more commonly associated with a category 4. But other researchers have found that climate change is increasing storm frequency and making historical data obsolete.

Forecasters predict that two storms, both currently tropical depressions, will enter the Gulf next week. One may be headed for “Houston’s doorstep,” as Houston meteorological whiz Eric Berger noted on Twitter. It’s too early to predict how severe the storms will be, if they do make landfall in Texas.

O’Rourke is convinced that a direct hit by a major hurricane is an inevitability within the next couple of decades. For years he has been urging local politicians to get started on developing a land barrier to protect the Ship Channel, but no such project is yet in the works. O’Rourke compares himself to Cassandra, a priestess from Greek mythology who is cursed with foretelling the future while never being believed.

“What drives public policy is the squeaky wheel. It’s complaining and immediate need-driven,” O’Rourke said. “But there’s not a large group of citizens demanding that the government take this threat seriously. I might as well be talking about a giant asteroid that’s going to hit us.”

Two months into hurricane season, O’Rourke joined his wife, an international relations expert, on a podcast episode to discuss hurricanes. His calming voice lacks the strident urgency you’d expect from an environmental alarmist who regularly obsesses over doomsday scenarios. Instead, the 73-year-old native Houstonian laid out his case with the calm precision you’d expect from a veteran lawyer who has spent the past four decades suing large polluters in civil court.

O’Rourke says he first realized the Ship Channel was vulnerable to a hurricane more than ten years ago, while he was working on a high-profile case involving a set of paper mill waste pits along the San Jacinto River, which feeds into the Ship Channel. The pits were already leaking cancer-causing dioxins into the river. A storm surge, experts argued, would further destabilize the toxic dump, allowing the chemicals to contaminate wildlife and putting anyone who came into contact with them at severe risk. O’Rourke calls expert testimony in the courtroom his “holy shit” moment.

Ever since, he’s been warning a who’s-who list of local officials, through in-person meetings, phone calls, and emails, about the threat that a sizable storm surge poses. Last year, he blasted out a video warning about the Ship Channel’s hurricane vulnerability to 150 officials and staffers from the Harris County Flood Control District, the Harris County Commissioners’ Court, the Port Authority of Houston, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and the state’s General Land Office. The goal, he said, was to get an official from the commissioners’ court or the port authority to hire a firm to produce a multimillion-dollar environmental impact statement for a prospective protective barrier.

O’Rourke’s efforts to spur local action have been to no avail, a development he finds shocking three years after Hurricane Harvey made clear the city’s vulnerability to severe storms. Downgraded to a tropical storm by the time it settled over Houston, Harvey never threatened the Ship Channel, but its torrential rainfall still managed to overwhelm the city, displacing tens of thousands and leaving one third of Houston underwater. Though local politicians and business leaders have on occasion acknowledged the threat of a more direct hit, there is no plan in place to build a coastal barrier—while Houston’s population and its ports continue to grow. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Texas General Land Office are working on a coastal protection study, though serious engineering and environmental questions persist and any barrier is at least a decade away from being completed, according to the Houston Chronicle.

There are several proposals for protecting the Houston region from the kind of superstorm that leveled Galveston in 1900, in what remains the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history. The most well-known plan is the Ike Dike, a seventy-mile-long, $23 billion to $31 billion coastal barrier and gate system designed to keep storm surge out of Galveston Bay. O’Rourke advocates, instead, for the “Galveston Bay Park Project.” The idea is to use dredged-up sand, rock, and mud to build a string of publicly accessible islands that would buffer the western side of Galveston Bay and the Ship Channel while also providing locals with new destinations for camping, fishing, migratory bird-watching, and marina access.

At an estimated cost of $5 billion to $7 billion, the project would be far cheaper than either the Ike Dike or the cost of recovering from an epic natural disaster. Proponents believe the project could be financed at the county and state level, ideally with the help of local industry, and be completed within five years. Unfortunately, O’Rourke said, officials haven’t completed the kind of environmental impact analysis necessary to move the proposal forward in that timespan. It’s as if, O’Rourke said, the city has utterly failed to heed “the great wakeup call” that was Hurricane Harvey.

“The ocean is getting hotter and the hurricanes are getting stronger,” he said. “At this point, we really are playing Russian roulette with the largest petrochemical complex in the United States.”

But Dennis Winkler, interim executive director of the East Harris County Manufacturers Association, maintains that many of the area’s companies are better prepared than critics say. He said the organization’s members regularly prepare for extreme weather and have long-established emergency plans in place that are adjusted with each storm. “Manufacturing facilities are designed and built with major storms in mind,” Winkler wrote in an email. “Specific construction elements can include reinforced manufacturing equipment that helps improve the overall structural integrity of a facility in accordance with industrial building standards for hurricanes.

“Dikes and levees are incorporated to reduce the risk of chemical releases,” he added. “In the event of a major storm, plants may reduce operations, shutdown a facility, evacuate personnel, and physically secure equipment.”

Shutting down a facility is not as easy as “flipping a switch,” Rivera of the chemical council noted, pointing out that facilities have material flowing at very high temperatures and pressures that require time to contain, treat, and remove from the facility. That’s one reason, he said, that his organization supports a coastal barrier like the Ike Dike. “If you have a major flood event, you can’t 100 percent control every little bit of material on site,” he said, “but we go to great lengths to make sure we are containing any potential release of any kind, and our industry has a pretty good track record spanning decades of managing these storms and learning from every single incident.”

O’Rourke isn’t alone in believing the Houston Ship Channel represents an environmental cataclysm in waiting. Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo has acknowledged the threat. And in 2016, the Texas Tribune and ProPublica published “Hell or High Water,” a data-rich project unpacking how a hurricane directly hitting the Ship Channel would kill thousands and devastate the economy. The project relies heavily on data from Hurricane Ike, the 2008 category 2 storm that narrowly missed the channel but still managed to kill 74 and cause $30 billion in damage. A direct hit, the project concluded, would shutter at least ten major refineries, spiking gasoline and consumer goods prices while crippling the U.S. economy.

Experts at Rice University’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education, & Evacuation from Disasters Center (SSPEED) have also publicized the threat for years. O’Rourke, a Rice graduate, has relied on their expertise. Though he has no formal partnership with SSPEED, he is in regular touch with Jim Blackburn, an environmental law professor who teaches in the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department at Rice and is one of the center’s most outspoken members on the topic of the Ship Channel’s vulnerability.

Though the center’s experts study possibilities and probabilities, Blackburn told me there is already a precedent for rising waters lifting aboveground storage tanks off their foundations and carrying them away. When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans, one such tank full of oil there was lifted and damaged, unleashing a spill that contaminated a local neighborhood, according to StateImpact Texas. During Ike, another tank outside Beaumont buckled amid rising waters, which also flooded a chemical plant.

Blackburn said estimates of “spill volume” during a storm surge—200 million gallons for a 28-foot storm surge, for example—don’t account for the fact that the Ship Channel is chock-full of shipping containers, the 40-foot-long metallic boxes that weigh tens of thousands of pounds and have become popular modular homes. Blackburn said the area is home to two big container terminals and hundreds of container storage sites. “And the point is containers float,” he noted. “They’re just like metal boats, and in a storm they’ll go flying. When you factor in containers, the potential for damage is much greater.”

Asked whether he considers O’Rourke’s Chernobyl comparison hyperbolic, Blackburn agreed that a major hurricane striking the Ship Channel would be worse. When the Soviet nuclear power plant exploded, he said, those tasked with cleaning it up at least had the benefit of knowing what sort of material they were dealing with. The chemical soup left behind by a direct hit by a major hurricane would not only be terrifyingly mysterious in nature, he said, killing wildlife and making large portions of the region unlivable. It would also cast a pall over southeast Texas for decades to come.

“To lose the bay would be this huge red flag to the rest of the United States to stay away from this part of the world,” Blackburn said. “You could say goodbye to local seafood, to economic development, to entire communities, and to one of the most prolific estuaries in the United States.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Hurricane Harvey

- Houston