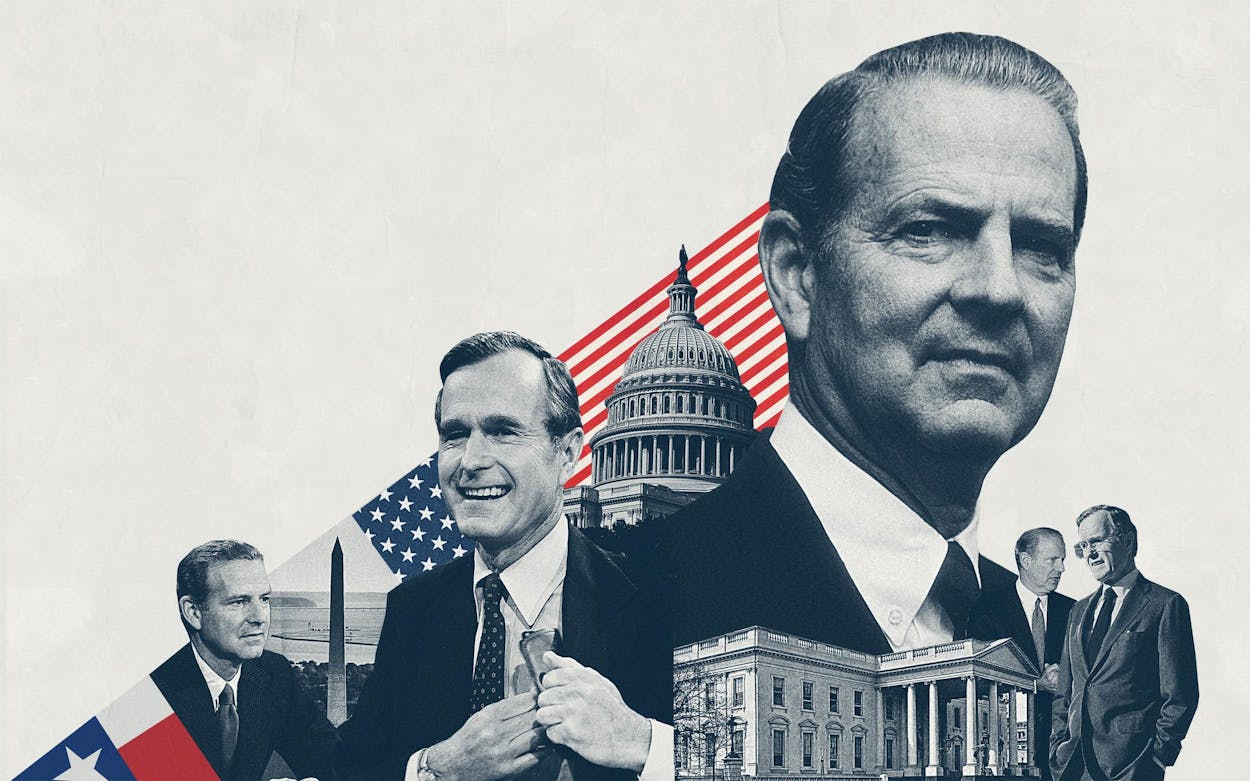

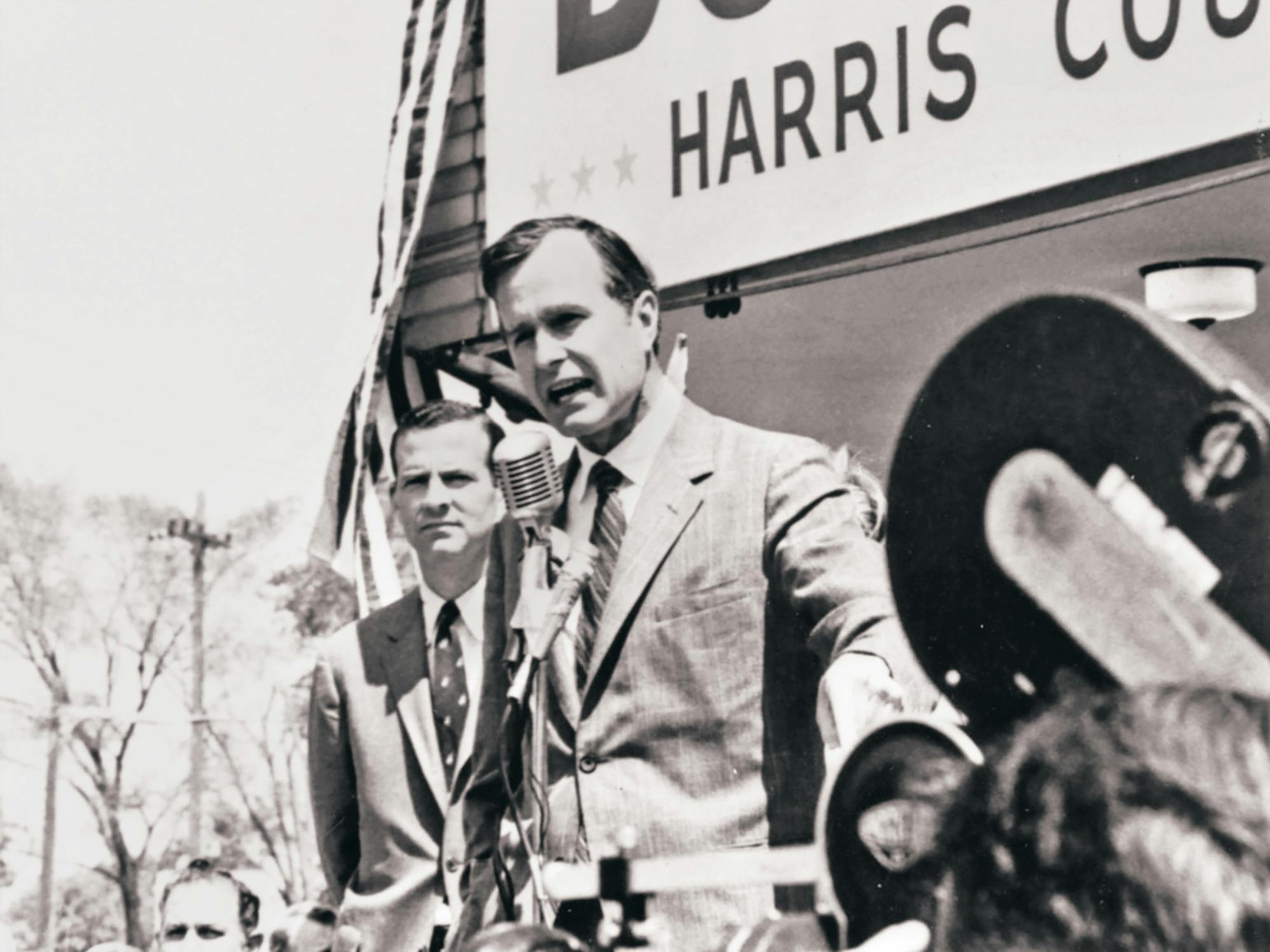

As he reached his late thirties, Jim Baker, son, grandson, and great-grandson of lawyers, was growing bored with the law. He had practiced for years at the Houston firm Andrews Kurth but told his cousin that he “didn’t want to spend his whole life on oil and gas leases.” So when his friend George H. W. Bush was looking around for a successor to run for his House seat while he mounted a bid for the Senate, Baker was intrigued.

Up until then, Baker had preferred hunting to voting. He was not even a Republican. His grandfather had warned him to “work hard, study, and keep out of politics,” a family rule going back to the Civil War. But Baker told Bush he was interested anyway and began sounding out possible donors and supporters. Then one day in August 1969, he abruptly changed his mind. He would not run after all.

In a handwritten letter to Bush, never before published, Baker explained why: his wife, Mary Stuart, was dying of cancer. Despite an operation, he told Bush, her cancer was coming back, and the doctors had told him that she would be at her sickest just as the campaign would hit its peak.

Then Baker dropped another bombshell. “George, Mary Stuart does not know her true prognosis,” he confided. “I have not told one person, including my mother, about her true condition in order that it not get back to her,” he added. “I think it important to her, the children, and me that she not spend whatever time she has left worrying over what’s to come.”

Baker had not told his mother, his children, or even his wife the biggest secret in their lives. The one person he told, the only person he trusted enough to share his awful truth, was George Bush. A secret that big creates a bond as nothing else will.

Unlike George Bush, a transplant from Connecticut, James Addison Baker III is a Texan through and through. He was born at Houston’s Baptist Hospital on April 28, 1930, the son of James A. Baker Jr. and his wife, the elegant society hostess Bonner Means Baker. In the spidery handwriting on his birth certificate, his father’s occupation was listed simply as “Lawher,” although in actuality he was not only a prominent attorney but a banker, a developer, a war hero, and a demanding taskmaster who would expect much from the son for whom he had waited through thirteen childless years of marriage.

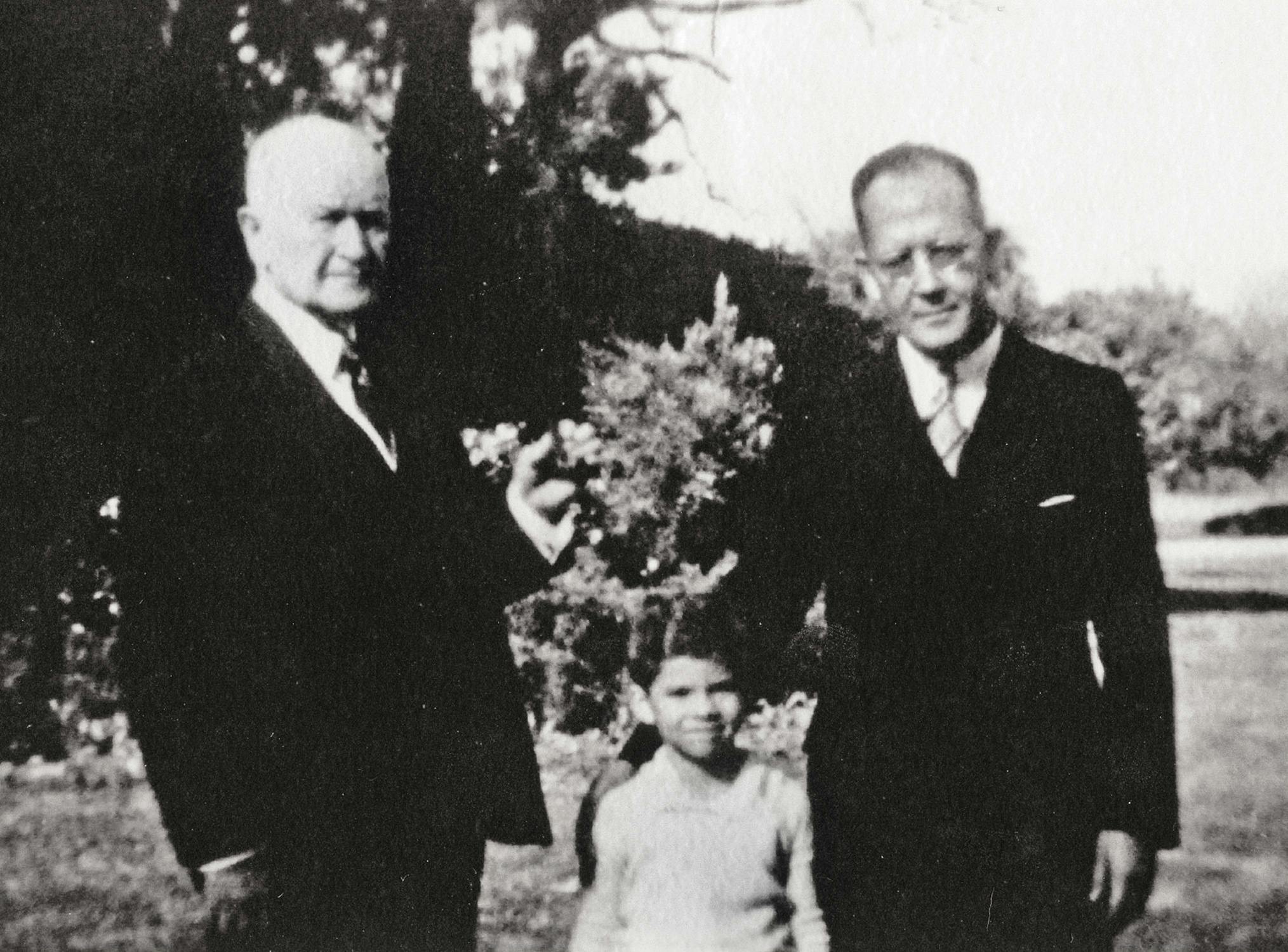

The world that Baker was born into had been shaped, to a remarkable degree, by his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather before him. He lived in a neighborhood of their design in the shadow of what was then called the Rice Institute, a great new center of higher learning that they had built and whose affairs they had overseen. He grew up playing tennis, swimming, and hunting at clubs they had helped to found. The city of Houston that boomed around him was named for his great-grandfather’s friend, its buildings financed by the bank his family helped to run. The art museum and the city’s leading service charity were established by his grandparents. When he got old enough to go to school, Jimmy attended the city’s most prestigious private academy; his father, naturally, was chairman of the board.

“Jimmy,” his mother would say to him, “you have quite a legacy to live up to.” He would be raised to follow the family tradition more than would any of the hordes of cousins he grew up with or his younger sister, named Bonner, after their mother. “He was the hero son,” said one of those cousins, Stewart Addison Baker. “He was the person who was expected to succeed in a grand way, and I think even when he was a young man, it was assumed that he would fulfill those expectations.”

The Bakers of Texas had always been lawyers, and they passed the profession down to their sons along with the name—and the burden of living up to it. The first James Addison Baker arrived in Texas in the 1850s from Alabama, settling in the newly founded town of Huntsville, where he met Sam Houston, the famed hero of the Texas Revolution. While fighting for the South during the Civil War, Baker was elected judge and eventually moved to Houston, where he joined a law firm founded by two other Confederate veterans, Peter Gray and Walter Browne Botts. For the rest of his life, he would be known as Judge Baker, although he made his mark representing the railroads that were turning Houston into a major center of commerce.

His son James A. Baker Jr. was called Captain Baker for his time in the Houston Light Guards, a uniformed company of the state’s National Guard formed by Confederate veterans after Reconstruction, even though he never saw action of any kind. But he earned national renown for his role in “America’s most remarkable murder case” after one of his longtime clients, the plutocrat and philanthropist William Marsh Rice, suddenly died in New York. A lawyer who tried to submit a new will with himself in charge of the bulk of Rice’s estate was convicted of murder in part because of Captain Baker’s work. The theft of the Marsh fortune was thwarted, and it instead served as the endowment for what would become Rice University.

The next James A. Baker, who also ended up being known as Junior, really did fight in combat, serving in the trenches of France under General “Black Jack” Pershing during World War I and at one point capturing three German soldiers singlehandedly. He went on to the family firm, now known as Baker Botts, and helped build it into one of the major law practices west of the Mississippi on the back of the discovery of oil that transformed Texas into an energy powerhouse. “He was a central figure in the coming of age of both his law firm and his city,” as the firm’s history put it.

He was also the central figure in the formation of his son’s character. He was a “stern disciplinarian,” as young Jimmy Baker’s cousin Preston Moore put it. If Jimmy did not wake up by 7 a.m. on a Saturday, his father would splash cold water on him. He would chastise Jimmy because his sister was doing better in school. He billed his son if he drank more than one soda at the club. Jimmy’s friends “were a little bit afraid” of his dad, recalled one, Wallace Stedman Wilson. Together, they came up with a nickname for the old man: the Warden. The name became all the more apt when Jimmy was about fourteen or fifteen and he and some friends got in trouble for shooting out streetlights with a Benjamin pump air rifle. The police rounded them up, took them to the station, and called their parents. One by one, his friends’ parents arrived to take their sons home. Not the Warden. “He said, ‘Let him stay there for the night,’ ” Baker recalled to us many years later.

The Warden dictated everything about his early path in life, sending Baker east to his own alma maters, the Hill School, in Pennsylvania, and then Princeton University. After a stint in the Marines, Jimmy was told to apply to his father’s other alma mater, the University of Texas School of Law, because, the old man argued, it would be better to learn in the state where he would practice. But it was not enough to go to the same high school, college, and law school as his father—the Warden insisted that his son pledge the same fraternity too. Never mind that Baker was by then 24 years old and married, with a baby on the way and two years of military service under his belt. As ordered, he signed up for Phi Delta Theta and gamely endured the hazing rituals administered by undergraduates. “I had these young kids that were five and six years younger than I was telling me, ‘Sit on that ice block in burlap,’ and they would drop raw eggs down my throat,” he remembered. “I did all that for my dad.”

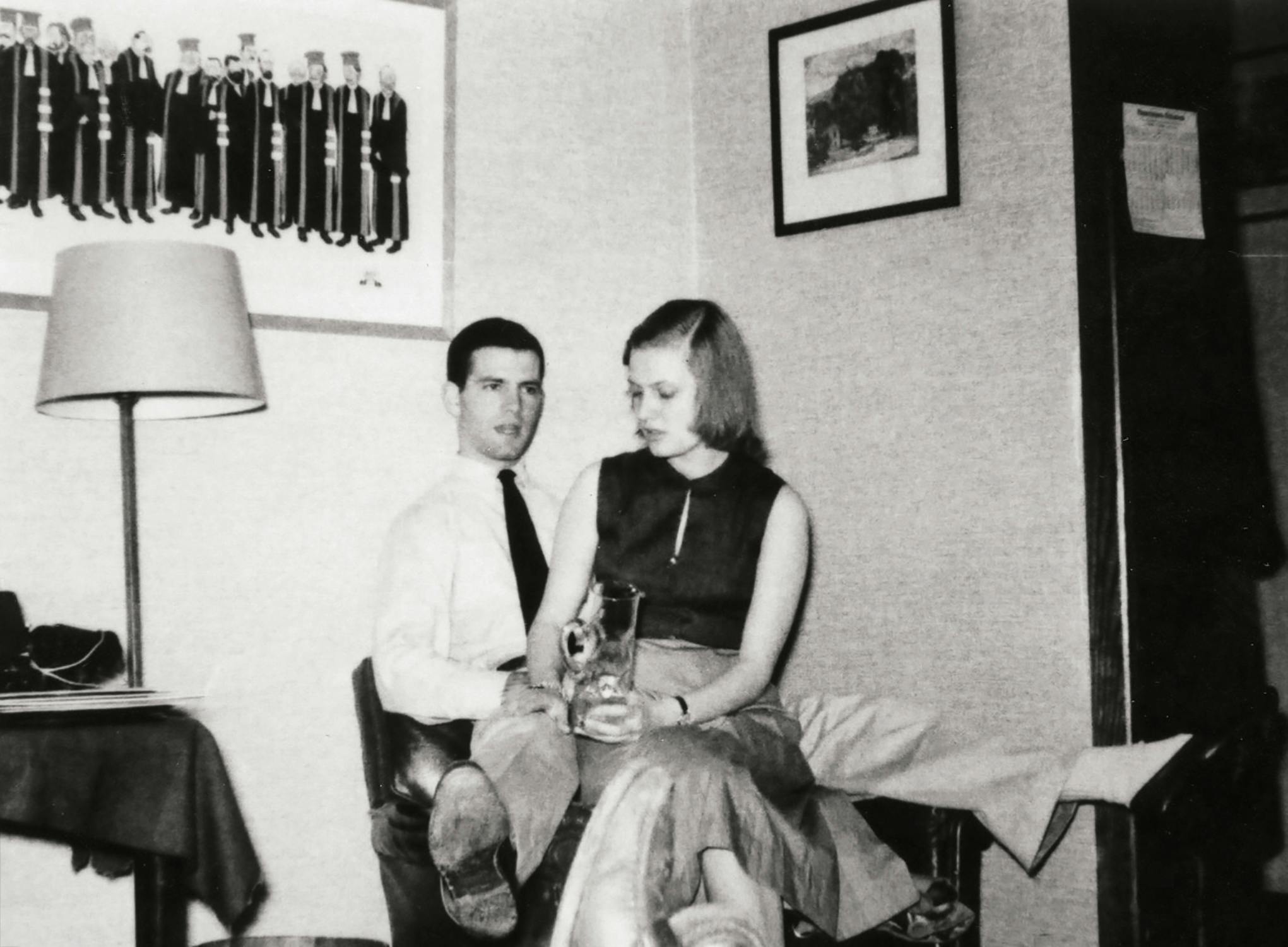

Baker met Mary Stuart McHenry during a spring break trip to Bermuda in his sophomore year at Princeton, spotting her at a party on the beach. An insurance salesman’s daughter from Dayton, Ohio, and a student at Finch College, a small finishing school on the Upper East Side of New York, she was eighteen, attractive, and full of life. They kissed on the beach. Baker fell hard. “I’ve got the screaming A-bomb hots for you,” he wrote her from Princeton as soon as he returned, adapting the vernacular of the early Cold War nuclear standoff. “It was just a wonderful love affair,” remembered David Paton, one of Baker’s Princeton roommates. “She was this very simple, pretty, unaffected, cheerful girl who just adored him, and I think that simplicity and that uncomplicated love was something that was just unusual for him.”

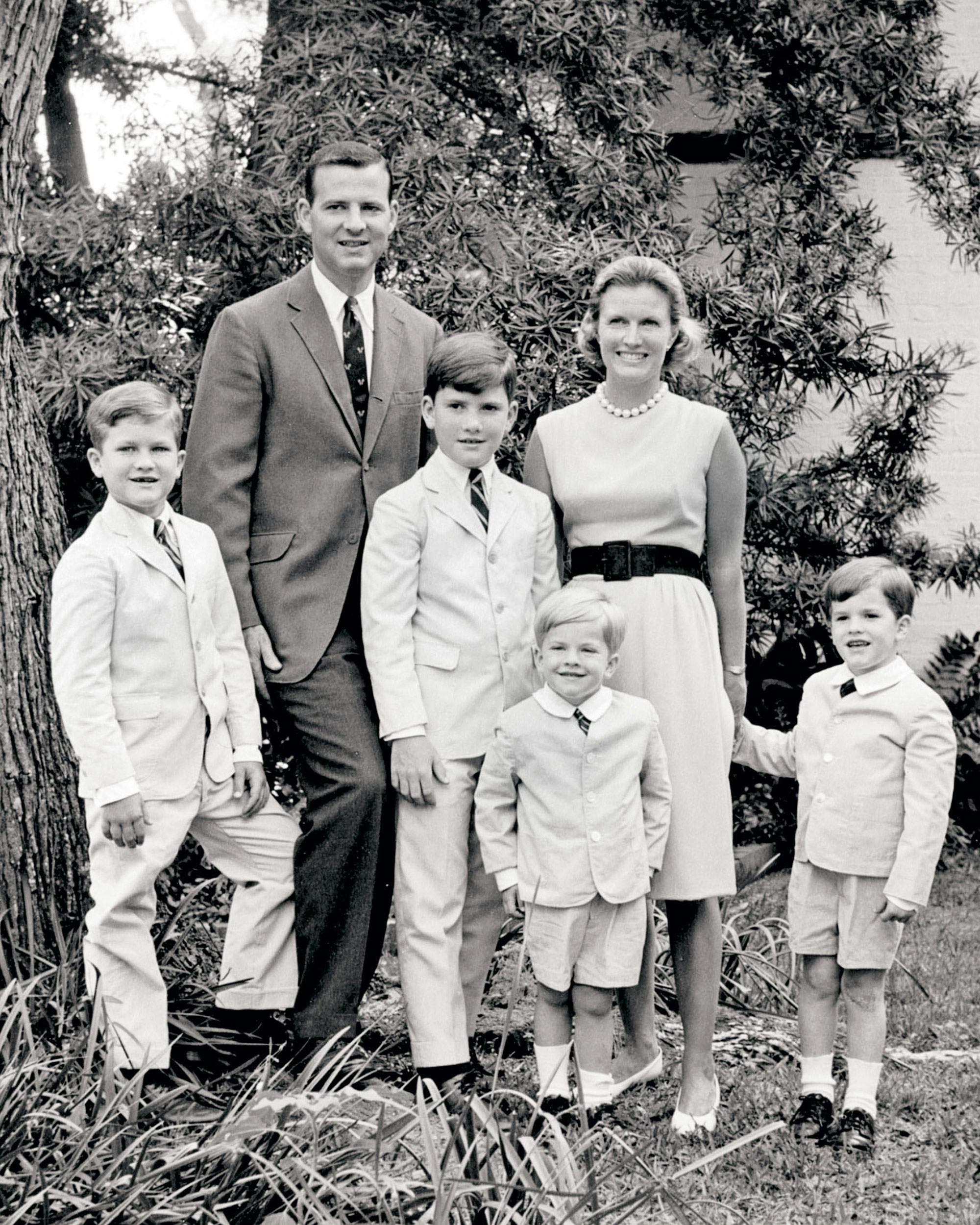

They married in Dayton on November 7, 1953, with Paton as the best man, and by the following fall they had the first of their four sons, James Addison Baker IV, or Jamie. Two years later came Stuart McHenry Baker, whom they called Mike, and a few years after that, they were joined by John Coalter Baker and then, thirteen months later, Douglas Bland Baker.

Baker’s professional life, though, did not immediately go according to plan. His father’s ambition to bring him into Baker Botts was foiled by an anti-nepotism rule that the partners refused to waive. “I was devastated,” the younger Baker said, “absolutely devastated.”

Instead, Baker went to work at Andrews, Kurth, Campbell & Bradley, another blue-chip Houston firm, where he was paid $400 a month to handle wills and trusts, property disputes, and business mergers. He was still dependent on his father, who put up the money so that he and Mary Stuart could buy their first house and regularly passed along checks for various purchases—to send the boys to summer camp, reupholster the furniture, buy new suits, repair the fence in the backyard, purchase a new station wagon, finance a vacation, even pay the doctor’s fee for the delivery of one of their sons. When Baker bought Mary Stuart a mink coat in 1963 for $1,800, about 10 percent of his annual salary at the time, his father volunteered to pay half.

The checks were often accompanied by notes with the dry, impersonal tone of a lawyer communicating with another lawyer rather than a father with a son. On Baker’s twenty-ninth birthday, his father sent a check for $50 and a typewritten cover page. “You have always been a very satisfactory son and given both of us much pleasure over the span of your life,” he wrote, signing it, “Devotedly, Daddy.”

On the wall of the Houston Country Club, the winners of the annual tennis tournament were listed in long rows on large wooden plaques. On the one titled “Men’s Singles Championships,” the name James A. Baker III was engraved next to the year 1958. Also next to 1959. And 1960. And 1961. By the time a young oilman named George Herbert Walker Bush moved to Houston and joined the country club looking for someone to team up with in doubles, all he had to do was check the plaque to find a promising partner.

Bush was a Yankee émigré who had spent the past decade searching for oil in Texas. Tall and proper, with a New England accent and an Ivy League pedigree, he was not a natural fit in Texas. But he was a “friend maker,” as his brother Jonathan Bush put it, the kind of person who would meet someone during the day and bring him home for dinner that night unannounced, much to the chagrin of his wife, Barbara, who was left scrambling to add another plate at the table.

The son of an investment banker who later served as a senator from Connecticut, Bush headed to Texas a few years after returning from a heroic stint as one of the youngest Navy pilots in World War II. He took a job as an oil field equipment salesman for Dresser Industries, on whose board his father sat. His first home in Texas was a rented two-room duplex in Odessa, where the family had to share a bathroom with a mother-and-daughter prostitute team next door. They later moved to nearby Midland. By the time Bush made the five-hundred-mile move to Houston in 1959 and enrolled his oldest son, George W., at the Kinkaid School, which Baker had attended, he was president of his own small oil firm, Zapata Off-Shore Company.

Barbara Bush used to joke that since Election Day often fell around the same time that hunting season opened, Baker would pick shooting over voting.

Bush and Baker first met through a small-world connection involving Mary Stuart. Growing up in Dayton, Mary Stuart had been friends with Teensie Bush, a cousin of George. When Bush and his growing family moved to Houston, Teensie got in touch with Mary Stuart and suggested they meet. As it was, George was already using Baker Botts for legal work for his oil exploration firm. And they would later discover that his wife Barbara’s aunt had taught Mary Stuart in school in Dayton.

The families had much in common. Jamie and Mike Baker were roughly around the same age as Jeb, Neil, and Marvin Bush. They lived not far apart and would regularly get together for Sunday barbecues and games of touch football. At Christmas, the Bushes would invite the Bakers over for cocktails.

But the friendship between Baker and Bush would truly be forged on the tennis courts of the Houston Country Club, which Baker’s grandfather had helped to found in 1908, when it opened the first eighteen-hole golf course in Texas. By the mid-sixties, the tennis pro at the club put Baker and Bush together as a doubles team. Neither had a particularly strong serve. Baker used to joke that Bush’s was so weak that the future president could hit the ball and run over to the other side of the court in time to return it himself. Bush kidded that Baker needed him to back up his “powder puff serve.” Still, Bush admitted to us before he passed away, “Baker’s the better tennis player than I am.”

But Bush played the net well, and with Baker’s killer ground strokes, they made a formidable team. Together, they won the doubles championship at the club two years in a row. They learned to anticipate what the other was thinking without being told, a connection that would prove crucial later in life. “They’re both enormous competitors,” George W. Bush told us. “They want to win.”

At the time, Bush was eyeing a political career as a Republican in a state still dominated by Democrats. Baker, six years younger, was an apathetic Democrat who took seriously his grandfather’s warning to stay away from politics. Mary Stuart was the politically active member of the family, an Ohio Republican among the Southern Democrats. She once hosted a Republican precinct meeting in their living room, and only one other person showed up. “I served him drinks,” Baker liked to tell people years later. Otherwise, he could hardly be bothered. Barbara Bush used to joke that since Election Day often fell around the same time that hunting season opened, Baker would pick shooting over voting. He later swore that was not true, but it seemed a fair reflection of his priorities in those days.

The major political events of the era seemed to largely escape Baker. The Cuban Missile Crisis, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement—Baker’s letters from the time refer to none of them, nor would he summon strong memories of them later in life. His only real involvement in politics was largely tangential. He contributed money to Waggoner Carr, a Democrat who ran for Texas attorney general in 1960 and lost, then ran again successfully in 1962. But for a lawyer like Baker, that was just business.

Baker looked up to his friend, though. Bush had been a World War II hero and the son of a senator from Connecticut. After his father retired, Bush wanted to go to Washington too, mounting a losing challenge against Texas senator Ralph Yarborough in 1964. Baker, still a Democrat, essentially sat on the sidelines, although he sent a condolence note afterward. “My dear George,” he wrote. “You ran a great race against almost overwhelming odds. The cards were stacked against you from the beginning and the breaks never came your way. Most certainly, you are disappointed, and so am I. You could not, however, possibly have any regrets.” Bush then threw in his hat for a House seat from Houston in 1966, and this time he won. Bush ran unopposed two years later and was gaining attention at the national level. Baker began to take notice. “I was sort of in awe of him for a while,” he confessed.

As Bush was networking his way around Washington, Baker was settled into a life of comfortable privilege in Houston. He made partner at the firm, and he and Mary Stuart decided to build a new home for their family of six. Mary Stuart chose the architect and designed what would be her dream house. But in February 1968, their life took a sudden, dark turn. Mary Stuart developed a red spot on her breast. The doctor who examined her thought it was mastitis, a simple breast infection, and told her it would be fine but to come back if it persisted.

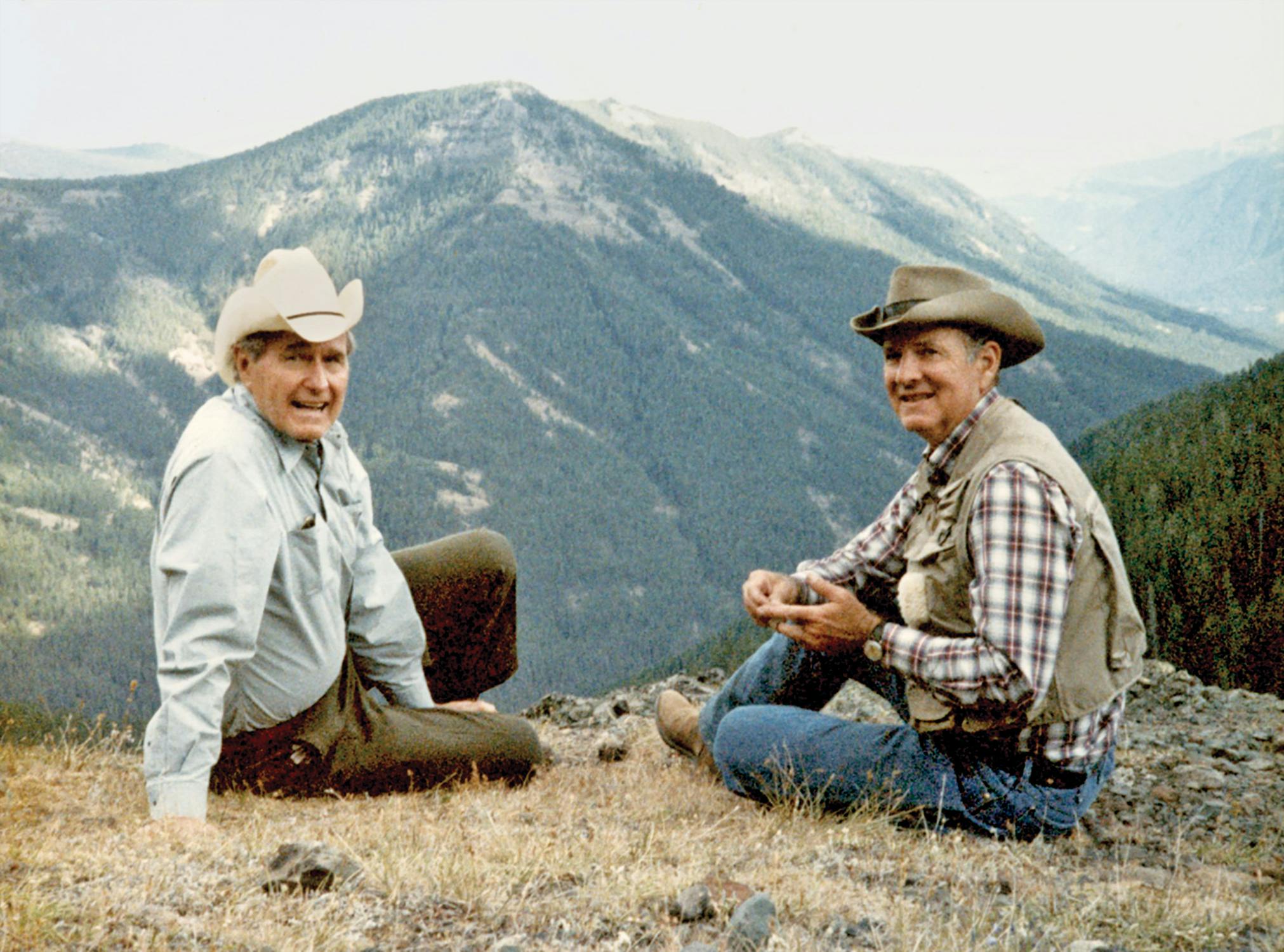

For the next six months or so, everything seemed all right. Then she and Baker went on a trip with friends in the Wyoming mountains, camping at Open Creek, near the headwaters of the Yellowstone. One day they rode 26 miles on horseback, but Mary Stuart could hardly manage the exertion. “It damn near killed her,” Baker recalled. When they returned home, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Their oldest son, Jamie, was already away at boarding school, but they sent the other three boys to live with friends for months.

After an operation, Mary Stuart returned home in February 1969, and they brought the boys back too. Baker thought everything was back to normal, so when Bush approached him about running for his House seat he took an interest. In typical fashion, Baker began methodically researching what would be involved in taking on such a race. He met with people he trusted as well as political figures in the district to sound them out. Reactions were mixed—“some pro, some con,” as he put it at the time.

But as Baker seemed ready to jump into the race, Mary Stuart’s doctors told him that her condition had worsened again and that she did not have long to live. At the beginning of 1970, with the new house almost ready, Mary Stuart fell ill and returned to the hospital. “She’s not going to make it,” Baker finally told his cousin Preston Moore, who was like a brother to him. The younger boys were brought to see their failing mother in the hospital, but Baker never let on just how serious the situation really was.

The last people outside the family to visit Mary Stuart before she died were George and Barbara Bush. “The treatment was so terrible,” Barbara told us before she died. “The medication was barbaric. I don’t think the boys knew. I think Jimmy knows that was a huge mistake he made.”

Mary Stuart died on February 18, 1970, at 38 years old, having never lived in the finished home she had built for her family. Baker was at her bedside. He later told Jamie that he was holding her hand, distraught at her pain. “He prayed that she would not suffer, and she died a minute later,” Jamie said. “And he took that as being an answer to prayer.”

It was a Wednesday morning, and after Mary Stuart was gone, Baker drove over to the Kinkaid School and pulled the three younger boys out of class. He took them on a walk across the lawn at the headmaster’s house.

“God came today,” he told them.

As it turned out, Baker had not fooled Mary Stuart. He may not have told her what he knew—what he had shared with George Bush in that letter months earlier—but she understood how dire her condition was. She did not talk about it with her husband, to spare him. Each of them was trying to protect the other.

A day or two after her death, Mary Stuart’s good friend Susan Winston came by the house. She had something to tell Baker. During a trip with two other friends to Florida the previous November, she said, Mary Stuart had confided in her that she knew she would not live long—and she told Winston that she had hidden a letter to her husband in a built-in chest in their home to be read after her death. Winston found it and gave it to Baker. He wept as he read it, as he would every time he reread it over the next fifty years.

“My dear sweet loving and loveable Jimmy,” she wrote, “I am suffering so much and cannot get relief. If God would take me now I would be grateful. I am sure he will not for though my time to die may not be far off, it is not now. I am not afraid. The thing that grieves me most is to see you suffer so. . . . Since the night I kissed you on the beach at Bermuda I have loved you more than anybody could ever love another body. If I have seemed selfish in wanting to be with you constantly it’s only that I’ve lived for the times when I could be close to you and to touch you. . . . Thank you my love for the best life anyone who has ever walked this earth has had. . . . Don’t be sad. Rejoice—and come to me someday.”

After his wife died, Baker would come home at night and drink a few more martinis than he used to. “If I was ever going to become an alcoholic, that’s when I would have done it,” he said.

Left alone with four boys at age 39, Baker was lost. “He would go to the window and stand and just stare out of the window,” recalled Beatrice Green, his childhood nanny, who still worked for his mother. Baker came home at night and drank a few more martinis than he used to. “If I was ever going to become an alcoholic, that’s when I would have done it,” he said.

Ultimately, Baker would rebuild his life with the help of the same woman who brought him his late wife’s letter. Susan Winston was not only a close friend of Mary Stuart’s but was married to Baker’s close friend James “Jimbo” Winston. Jimbo’s drinking, however, tore apart their marriage, and they divorced around the time of Mary Stuart’s death. Within a couple years, Susan and Baker fell in love and eventually sneaked off to get married, bringing their seven children together for a complicated real-life reenactment of the then-popular Brady Bunch television show.

The other person who would help Baker get back on his feet was George Bush, who urged him to help with his 1970 Senate campaign. “Bake,” he told his friend, “you need to take your mind off your grief.”

“George, that’s great, but there are two things,” Baker replied. “Number one, I don’t know anything about politics. And number two, I’m a Democrat.”

“Well,” Bush said, “we can take care of that latter problem.”

Eventually, they took care of both

Peter Baker is the chief White House correspondent for the New York Times, and Susan Glasser is a staff writer and Washington columnist for the New Yorker.

This article originally appeared in the October 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Hero Son.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- George H.W. Bush

- Houston