On paper, at least, Genevieve Collins would seem to be an ideal recruit for the Thirty-second Congressional District, a swath of Dallas and its suburbs that has long been a Republican stronghold. She’s young (34), well funded, and a native of the area who graduated from Highland Park High School and Southern Methodist University. She works at an education technology firm owned by her father, Richard Collins, a mega-wealthy Dallas investment manager and lavish GOP donor. A former college athlete who walks with a swagger, she possesses the toothy verve of a woman who has never encountered failure.

Collins is aiming to unseat Colin Allred, a voting rights lawyer and former linebacker for the Tennessee Titans who worked in the Obama administration before capturing what was thought to be a safe Republican seat during the Democratic wave of 2018. In Congress, where Allred was elected copresident of his party’s 59 freshmen, he sponsored a few bills (such as increasing veterans’ benefits and extending child tax credits) that never became law and was an early supporter of Joe Biden’s candidacy. But because of the Republican history of his district, he was also immediately identified as one of the most vulnerable Democrats on the Hill. Collins, in turn, was among the National Republican Congressional Committee’s first batch of Young Guns, the most prized recruits for competitive seats.

The campaign playbook Collins is relying on is a familiar one—perhaps too familiar. “I’m pro-Constitution, pro-business, pro-God,” she said in an early social media video. Another of her videos flashed images of the cowboy statue in Dallas’s Pioneer Plaza and of Collins taking target practice as she declared herself “one hundred percent Texan.” In a TV ad, Collins described what it means to be a Texas woman: “You have to be able to shoot, clean, and eat your kill one day and throw on a dress and work a boardroom the next.” Redolent of the Metroplex’s J. R. Ewing era, her message is manifestly tailored to nostalgia-prone white residents of a certain age with whom, unsurprisingly, Collins is shown chatting it up in a generic local diner on her campaign website.

But that’s no longer the essence of the Thirty-second District, which looks, thanks to Republican gerrymandering, somewhat like a well-fed horse, its hind legs astride the wealthy enclaves of the Park Cities while grazing from the pastured eastern fringes of the Metroplex, near Wylie and Lavon. And Allred has spent his entire life watching it change. Like Collins, Allred is relatively young (37) and was born and raised in the area. His upbringing, however, was quite different from hers. Allred never met his father, who is Black. He was raised by his mother, who is white, in neighborhoods where few looked like him—first Oak Lawn, then far North Dallas.

“It was predominantly white and noticeably older than it is now,” Allred told me. “It’s now more diverse in every respect. In many ways, it’s reflective of what’s happening across Texas.” The district’s biggest population center, Garland, is only 30 percent white, and many of the recent transplants are young professionals who have a dim view of Donald Trump. Indeed, in a sign of things to come, Hillary Clinton carried the district in 2016, 49 to 47.

That displeasure with Trump was still evident in 2018, when GOP incumbent Pete Sessions—a national party leader who had held the Thirty-second since its creation in 2001—was upset by Allred. The Democrat campaigned on a message of inclusiveness that focused on protecting the Affordable Care Act from Republicans like Trump and Sessions who had every intention of dismantling it. The district’s voters were unmoved by Sessions’s oft-repeated claims that Allred was a socialist disciple of Nancy Pelosi. Allred beat him 52 to 46.

Today, Genevieve Collins is reprising the “Pelosi socialist” critique, with, so far at least, predictable results. What the election forecasters at the Cook Political Report rated earlier this year as a “lean Democratic” race has now been moved to the “likely Democratic” column. Collins may possess skill on the shooting range, but when it comes to Texas politics, the Young Gun would seem to be firing blanks.

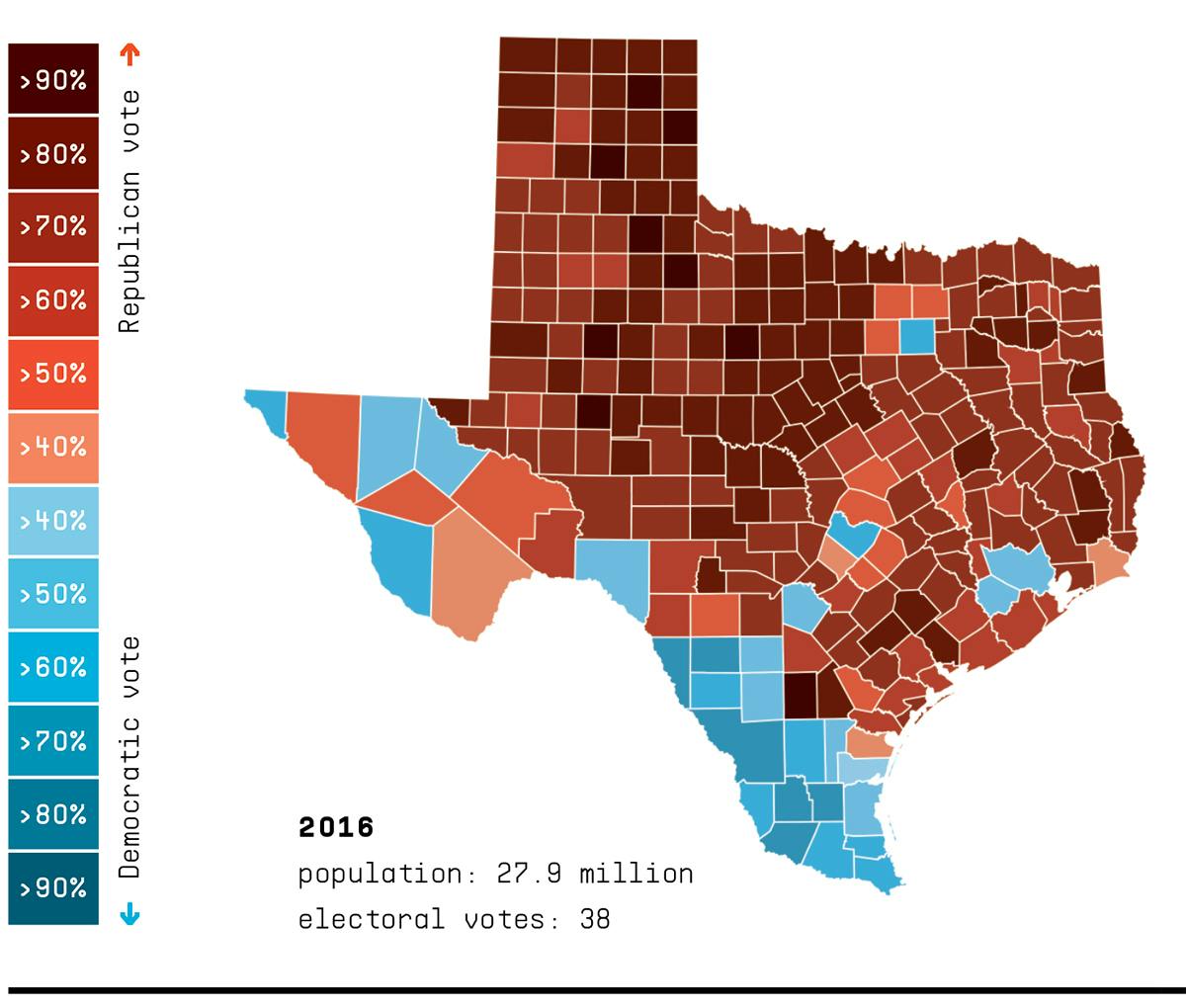

The election has yet to be decided, but one result can already be called: the Texas Republican party has lost its ability to speak to much of the contemporary electorate. That the cultural and demographic changes in Texas would at some point catch up to the state’s politics is an eventuality that the GOP’s leaders have done everything in their power to delay. The party has energized its base through culture-war issues such as opposition to immigration, gun control, abortion rights, racial justice protests, and COVID-19 restrictions. At the same time, its leaders have diluted the opposition vote through gerrymandered districts, dreamed up ways to make it more difficult for traditionally Democratic voters to cast their ballots, and scared off Democratic aspirants who can’t hope to match the deep pockets of rich conservative donors like Genevieve Collins’s father.

These maneuvers have made it easier to ignore the writing on the wall, but now the walls are closing in, making the message inescapable: Texas is not what Republicans are pretending it is. In the 1992 presidential election, 60 percent of the state’s votes were cast in greater Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and Austin. By contrast, in the 2018 midterms, 69 percent of the electorate came from those areas. But that isn’t the worst news for Republicans. As recently as 2014, 17 percent of the state’s electorate was Hispanic. Four years later, that number is 26 percent, and for all the data suggesting that Texas’s Hispanic population may be more conservative than its California counterparts, state Republicans usually count it as a rousing victory if they’re able to gain a 40 percent share of that demographic. (Governor Greg Abbott, whose wife is Latina, did so in 2018, gaining 42 percent of the Hispanic vote. That same year, Senator Ted Cruz managed only 35 percent, barely defeating Beto O’Rourke.)

Meanwhile, the fastest-growing racial group in Texas is Asian Americans, who have seen their numbers surge from 1.1 million in 2010 to an estimated 1.7 million in 2019. In the 2018 gubernatorial election, the incumbent Abbott handily beat Democratic challenger Lupe Valdez by 13 points. But according to exit polls, Abbott lost the Asian American vote by 18 points—still, a better showing than Cruz, who lost that cohort by a margin of 31 points.

What has kept Republicans in power is a dominant hold on a proportionately shrinking demographic: non-Hispanic white voters. Yet even that grip has become tenuous, for two reasons. First, the state GOP has maximized its rural turnout—there are few if any voters left to get. Second, and more important, the party is now struggling in the suburbs, as Collins is finding out. “Even more than the robust growth in eligible Hispanic, Black, and Asian American voters, the bigger driver of change in Texas is the migration [in the political views] of professional whites in the suburbs, particularly women,” Cook Political Report congressional analyst David Wasserman told me. “The shift was underway in the Obama era. Even when Romney won a healthy share of professional whites in 2012, the state House races in suburban areas were much closer. And now Trump is the accelerant. He’s provided rocket fuel for converting suburban Republicans to at least independents—which we saw in 2018, when professional whites turned out at a much higher rate than noncollege whites.”

Trump, of course, was not on the ticket in 2018. “I suspect we’ll see enough noncollege whites return to the electorate this November that Trump will still carry the state, very narrowly,” Wasserman added. Then again, the GOP’s winning margins in recent presidential contests have slowly but surely dwindled in Texas: from a 23-point margin in 2004 (Bush/Kerry) to a cool 9 points in 2016 (Trump/Clinton). While the president has his devoted base to count on, Biden has a few built-in advantages of his own. One is that, with the sole exception of Fort Worth, the state’s biggest cities and counties are run by Democrats, who are sure to keep a watchful eye on early and mail-in balloting procedures. Another factor in Biden’s favor is how the state’s Republican leadership has mismanaged the coronavirus. In June, Governor Abbott, long one of the most popular political figures in Texas, had seen a modest bump in his approval rating, to around 57 percent, according to a Quinnipiac University poll. But by late July only 48 percent held a favorable view of him. According to a different survey, in late August, only 35 percent of Texans approved of his management of the COVID-19 crisis—the seventh-worst rating among the fifty governors. No longer is Abbott an unqualified plus on the campaign trail.

“Donald Trump is not going to lose Texas, I can tell you that,” the president scoffed during a campaign stop in Dallas last October. But simply offering such a prediction was acknowledging the stakes: should Trump lose Texas, he has no path to victory. The electoral earthquake would shake the national Republican party to the ground.

Even a close Trump victory here is unlikely to protect the state GOP from further losses. While rural congressmen like East Texas’s Louie Gohmert and West Texas’s Jodey Arrington have everything to gain by embracing the president in their ultraconservative districts, other Republicans are caught between a Trump-worshipping base and a burgeoning suburban electorate that finds him repellent. That dilemma was on vivid display in late July, when Genevieve Collins made it a point to be among a group of Republicans who stood on the tarmac of the Midland airport to greet President Trump, who had arrived for a fundraiser. When later asked about the out-of-district sojourn, Collins’s campaign insisted, in an awkward statement that made no mention of Trump, that the candidate had made the trip because of her interest in the energy sector.

“Donald Trump is not going to lose Texas, I can tell you that,” the president scoffed during a campaign stop in Dallas last October. But simply offering such a prediction was acknowledging the stakes: should Trump lose Texas, he has no path to victory.

Collins is struggling to avoid the fate suffered by not only Pete Sessions, but also John Culberson, who moved far to the right to accommodate the GOP base and, in 2018, lost his west Houston district of nearly two decades to moderate Democrat Lizzie Pannill Fletcher. Those two losses are hardly flukes, evidenced by the fact that both seats are likely to remain in Democratic hands this November, despite heavy GOP spending. But the bad news for Texas Republicans doesn’t end there. Within months after Culberson and Sessions conceded defeat, six other GOP congressmen—Mike Conaway, Will Hurd, Bill Flores, Kenny Marchant, Pete Olson, and Mac Thornberry—elected to spend more time with their families.

Suddenly, it’s the Democrats who are playing offense. They’re favored to regain Hurd’s seat, the vast Twenty-third District, which spans much of West Texas. Marchant’s Twenty-fourth District, which covers a patch of the suburbs between Dallas and Fort Worth, possesses many of the dynamics of Allred’s neighboring district—“the rate of change there is insane,” says Wasserman—and is in significant danger of flipping as well. For the first time in recent memory, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee now views Texas as the most opportune target in the nation for growing the party’s majority in the House, with a good shot at picking up four or more seats. As the DCCC audaciously tweeted this past June, “Texas is ground zero for Democrats in 2020. #Texodus.” Or, if you don’t trust the DCCC, maybe you believe Ted Cruz, who declared in September, not for the first time, “Texas is a battleground.”

One summer day in 2011, I traveled to Sugar Land to have lunch with Tom “the Exterminator” DeLay, the town’s legendary former congressman. Once a peerlessly conniving House majority leader, DeLay had recently been sentenced to three years in federal prison for violating campaign laws but was out on bail, pending appeal. (His conviction was overturned in 2013.) I was researching a book on the House, so we confined our conversation to happier times, when DeLay was arm-twisting President George W. Bush’s legislative agenda into passage, while, in his spare time, merrily driving nearly every white Democratic congressman in Texas into extinction through brazen gerrymandering. After DeLay was done with his mapmaking, there was only one competitive district left in the entire state—out of more than thirty. DeLay’s own district, the Twenty-second, which includes most of Fort Bend County, southwest of Houston, has been one of the most reliably Republican fiefdoms in the state.

The clientele seated around us in the Italian restaurant that afternoon appeared to be uniformly white. A year later, Mitt Romney would beat Obama in the Twenty-second by 25 points. The district that DeLay built seemed impregnable. But this turned out to be far from the case, and also the reason journalists like myself are best advised not to limit their reporting to what they encounter at the local diner. By the time I sat down with DeLay, Fort Bend was already one of the fastest-growing counties in the United States, and fully 64 percent of its inhabitants were people of color. Mindful of the trends, the state’s Republican redistricting czars that year moved aggressively to protect DeLay’s turf, lopping off the district’s most heavily African American neighborhoods and shoveling them into an adjacent, safely Democratic district. “They’re carving, cracking, and packing these districts, and in so doing they’re setting up a situation where a tension builds up and all they can do is play to a shrinking base,” Sri Preston Kulkarni, a longtime resident of the district, told me recently.

In late 2017, Kulkarni, then 39, decided to test the district’s invulnerability. Two events drove him into politics. After seeing the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville on TV in Jamaica, where Kulkarni was visiting as a U.S. Foreign Service officer, he felt a “moral imperative” to get off the sidelines. Then, in December of that year, Kulkarni watched with dismay as Trump continued to stand behind the GOP’s Alabama Senate candidate, Roy Moore, even after credible allegations of pedophilia. “The Republican party was investing money in him,” he recalled. “And so I resigned from the Foreign Service, and I called back home to [Democratic party officials in] Texas and said, ‘I’ll do anything to stand up for our democracy. I’ll work for Beto.’ And they said, ‘Why don’t you come run? We need people with a national security background.’ ”

The son of an Indian American father who taught creative writing at Rice University and a mother who worked at Exxon as a systems analyst and is a direct descendant of Sam Houston’s grandfather, Kulkarni knew that he faced long odds against GOP incumbent Pete Olson, who had bested his previous Democratic opponent in 2016 by 19 percentage points. But he was also aware that Fort Bend had become an immigrant gateway, with more than a hundred languages spoken there. So he knew not to take as gospel the words of a Democratic strategist who, according to Kulkarni, said of the district’s growing immigrant population, “Don’t bother talking to them. They don’t vote.”

Kulkarni saw an opportunity. “I said, ‘They don’t vote because nobody bothers to reach out to them,’ ” he recalled recently. “So I specifically went out and recruited volunteers from all these different immigrant groups in the Asian community. It turned out that seventy-two percent of the ones we reached out to had never been called by either a Republican or a Democrat—and they’re the fastest-growing group in Texas.”

A career diplomat who speaks 6 languages, Kulkarni directed his campaign to communicate to the district’s electorate in 27 languages, from Spanish to Igbo. Though Olson won by 5 points, his loss was narrow enough that in July of 2019 he announced his intention to retire from the House. Kulkarni’s opponent this November will be former Fort Bend County sheriff Troy Nehls, who prevailed in the Republican primary by talking tough on immigration and claiming he was the lone candidate to have supported Trump’s border wall for years. But within days of his winning the runoff in July, all of his pro-Trump rhetoric—“I will stand with President Trump to defeat the socialist Democrats, build the wall, drain the swamp”—was scrubbed from Nehls’s campaign website.

In August, I made a phone call to Steve Munisteri, the 62-year-old Texas Republican party chairman from 2010 to 2015 and now one of its paid advisers. Munisteri and I have known each other since we were junior high school classmates in Houston’s Seventh Congressional District, then a Republican stronghold, but now held by Lizzie Pannill Fletcher. He is the quintessential Reagan Republican, having joined the Gipper’s 1976 presidential campaign fresh out of high school. Even during his chairmanship, as the tea party began to transform Reagan’s “Morning in America” ethos into Grievance Central, the ever-smiling Munisteri still projected his idol’s trademark sunniness, right down to his personal email address, which includes the phrase “Life’s great.”

I wanted to talk to Munisteri for two reasons. Optimism notwithstanding, he has always been a data-consuming realist, one who has been describing Texas as a “competitive state” since he first decided to run for party chairman in 2009. Still, Munisteri’s candid assessment of just how competitive the state had now become surprised me. “Hays, Williamson: these, to me, are true swing counties,” he said, referring to the traditionally conservative counties just south and north of liberal Austin that have, since time immemorial, been viewed as the boondocks of Central Texas. But Austin sprawl had changed all that. As a result, it wouldn’t be surprising if two of the state’s long-safest GOP congressmen representing two of its most artfully gerrymandered districts—John Carter in the Thirty-first and Roger Williams in the Twenty-fifth—were among the next crop of GOP congressional retirees.

Obviously, Munisteri’s party wasn’t going to stand by idly as one Republican-held district after the next shifted into the Democratic column. The GOP would have to find new voters somewhere. That was the other reason I wanted to talk to Munisteri. I had heard about the state party’s Volunteer Engagement Project, which he and veteran GOP strategist Karl Rove were spearheading. Its principal aim was to register as many Republicans as possible before the November election. So where was this new bounty coming from?

“A lot of them are Republican voters who moved here from out of state,” Munisteri explained to me. “Last month alone, we [registered] 73,000 of those.” Even greater in number, he said, were Texas Republicans who’d moved within the state and hadn’t yet bothered to register to vote in their new county. A third and smaller category consisted of so-called low-propensity voters, who, from consumer data, appeared to have Republican sympathies but seldom showed up to the polls.

At first blush, this seemed like a sensible political exercise. Munisteri and Rove were scouring the state for anyone who had, at some point in their lives, voted or behaved like a Republican and then getting them to register. But it also seemed rather puny in scale. When I described Munisteri’s efforts to Luke Warford, the state Democratic Party’s director of voter expansion, I could hear him struggling to suppress laughter. “Um, I’m actually pretty surprised he would admit that publicly,” Warford said. “First of all, if you’re saying that your largest target is Republicans who’ve moved from, like, Hays to Williamson County, those are not net new Republican voters. Full stop.”

Warford then turned his attention to Munisteri’s assertion that his initiative has registered a total of about 165,000 new Republicans. Though the state Democrats are cagey about releasing their own figures, they pointed me to recent registration statistics from two private firms. Both suggested that the Democrats were substantially ahead of the GOP in signing up new voters this cycle. “There are more than five million unregistered eligible voters,” Warford said. “And when you look at them, they skew heavily Democratic. We’ve done internal modeling. It’s seventy to seventy-five percent. They’re young, diverse, moving here from out of state. I cannot overstate that the electorate is rapidly changing, and that’s why voter registration is so central to our victory.” He added, “Not to be too smug about this, but I feel like Republicans haven’t registered voters in decades because they haven’t had to.”

Warford’s allusion to the state’s changing electorate underscored a stark reality: where the demographic frontier presents an invitingly fecund landscape to the Democrats, to the Republicans it resembles a desert of options. Back in 2013, when Munisteri was the party’s chairman, he had said to me, “The majority of Hispanics in Texas believe the Republican party is the party for the wealthy and is exclusive. And if you think about it, that’s probably the problem with the Republican party among any ethnic group.” Accordingly, Munisteri had pleaded his case to the national chairman, Reince Priebus, who responded by guaranteeing that the RNC would send the state party $80,000 a month to assist with Latino outreach efforts.

During our recent conversation, Munisteri told me that national support was a thing of the past. Since he left, “those funds from the RNC haven’t been forthcoming,” he said. He didn’t say why. He didn’t have to. Under President Trump and RNC chairman Ronna McDaniel, the national party’s focus has been on energizing its base. And so the Volunteer Engagement Project has committed itself to scavenger-hunting for hard-core Republicans (a decidedly white bunch) who don’t have a voter registration card.

The day after Munisteri and I spoke, a Washington, D.C.–based progressive group called the AAPI Victory Fund, a political action committee for Asian American and Pacific Islanders, made an announcement. It was sending $1 million to the suburbs of Texas, with the aim of registering multitudes of the state’s most meteoric demographic. At least one side was acting like Texas is a battleground.

We’ve heard this death knell before, of course. After Romney’s loss in 2012, establishment Republicans like Steve Munisteri fretted openly that the GOP would continue to lose unless the party broadened its appeal. It turns out they were wrong, at least for a couple of election cycles. Perhaps the GOP’s alley-fighting tactics—big ad buys, whipping up the base while limiting minority voter turnout—will prevail again in 2020. Even if they don’t, the conversion of a few Republican districts, or even suburbia writ large, into contested territory does not a purple state make. At some point, a Democrat must win statewide before Texas earns that distinction.

Though a Biden victory in Texas would amount to a kill shot to the GOP, it would likely come about only if he were already headed for a landslide, a romp across the electoral map from Maine to California. For the moment, his campaign is acting as if winning Texas isn’t realistic. Biden has yet to commit to a serious effort here, which would require heavy spending in several of the nation’s most expensive media markets.

Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick predicts that Trump will win the state by double digits. And other prominent Republicans, though not as boastful as Patrick, who is not up for reelection this year, look likely to prevail. Senator John Cornyn, unlike Cruz, has succeeded in garnering the national party’s early support and faces an opponent, MJ Hegar, who has so far fizzled where Beto O’Rourke sizzled in his run against Cruz. And a new star among the GOP congressional delegation, Dan Crenshaw, seems in little danger of losing his Houston-based district to his spirited but underfunded challenger, Sima Ladjevardian.

Crenshaw’s emergence is a reminder of how a dominant party regularly breeds new talent—while the state’s Democrats have suffered from a weak bench, at least until recently. After all, raising millions of dollars, cajoling thousands of strangers into voting for you, and weathering public attacks is often an unappealing career choice when you’re likely to be playing for the losing team. As longtime Democratic strategist Harold Cook put it to me recently, “Winning begets more winning, attracting a higher caliber of candidates, as well as more money to those candidates. And the opposite is also true. Democrats dug a deep hole for themselves because no one saw anything really being achievable.”

But Beto O’Rourke’s near-upset in 2018 and Colin Allred’s and Lizzie Pannill Fletcher’s victories that same year have perhaps augured a righting of the imbalance of star power. After 2020, the new buzzworthy Texan might be Sri Preston Kulkarni. Or it might be Gina Ortiz Jones, the openly gay Filipina and Air Force veteran who has raised more than $4 million in her encore effort to win the Twenty-third District seat being vacated by Will Hurd. Or perhaps the new breakout name will be the aspiring successor to Kenny Marchant in the Twenty-fourth: Candace Valenzuela, who as a child once slept outside a gas station in a kiddie pool with her homeless mother.

Or, conceivably, the new star in Texas politics might turn out to be an affluent white female Republican who came from behind in November to beat a Black Democratic incumbent. In her quest to do so, however, Genevieve Collins will likely have to confront what it means to be “one hundred percent Texan” in a state where 59 percent of its residents are people of color and 41 percent were born elsewhere. A new kind of majority is there for the taking. Pretending it doesn’t exist is the path to defeat.

Robert Draper is a writer-at-large for Texas Monthly, a contributing writer for National Geographic and the New York Times Magazine, and the author of the book To Start a War: How the Bush Administration Took American Into Iraq.

This article originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Elephant Tricks.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Donald Trump