Hall of Fame WR Don Maynard’s Name Is Front And Center In Football History

RUIDOSO, N.M. – What’s in a name?

To NFL Hall of Famer Don Maynard a name means everything.

“He has always been adamant about making a point that he played football at Texas Western … not UTEP,” said Scott Maynard, the son of the former Miner and one of the greatest receivers in NFL history. “The name of the school has been a sticky thing with him through the years.”

Texas Western became Texas-El Paso in 1966 when the Texas Board of Regents believed there was a need to unite many of its institutions. The change came just months after Texas Western defeated Kentucky 72-65 in to claim the NCAA basketball championship in one of basketball’s historic moments.

The legendary receiver, who is now 86 years old, has been suffering from dementia for several years and the younger Maynard has become a spokesman for his father, who is still in demand as his exploits continue to be remembered long after his playing career ended in 1974.

Along the way Maynard, who became an outstanding dual-sport standout for the Miners while at Texas Western, was front and center for plenty of history in professional football.

From Texas Western To The NFL

The son of a cotton broker, Don Maynard was born in Crosbyton, Texas, a tiny community some 40 miles northeast of Lubbock. The plains of west Texas made certain that cotton was the cash crop of the time. And the Maynard family took advantage of the big business it provided.

Like many families, the Maynards moved several times as the cotton industry continued to evolve. Maynard attended 13 schools, including seven high schools, while growing up.

“Dad had a normal childhood,” the younger Maynard said. “Like most other kids he took an interest in every sport and excelled in several of them.”

Maynard graduated from Colorado City High School and lettered in football, basketball and track in his final year. He was a Texas state high school champion in the low hurdles and high hurdles while competing for CCHS.

The athleticism Maynard put on display was enough to earn him a scholarship to compete in track at Rice University. But when the school spurned his desire to also play football for the Owls Maynard found himself at a crossroads.

“He used to come home several times that fall and would always have his bags packed with the intent on staying home,” Scott recalled.

Maynard’s brother was successful in convincing him to return to Houston for several weeks. After his freshman year ended so did Maynard’s time with the Owls.

Not sure what the future held, Maynard, at the suggestion of his father, decided to inquire about transferring to Texas Western. And when he learned the school was willing to allow him to compete in football as well as track, it was a matter of being signed, sealed and delivered.

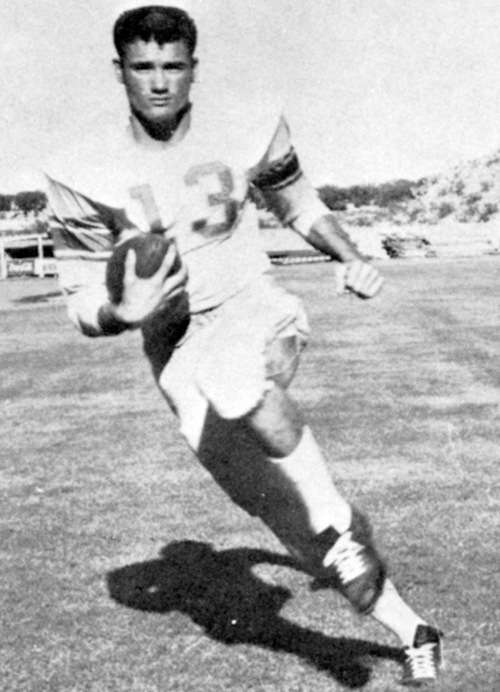

Maynard, who arrived on the El Paso campus in the fall of 1954, found success on the gridiron, despite seeing limited opportunities as a pass catcher with the Miners. In his three seasons he caught just 28 passes, but averaged an incredible 27.6 yards per catch. He scored 10 touchdowns through the air.

The versatile Maynard also saw time as a running back with Texas Western and ended his career with 843 yards on 154 carries (5.4 ypc) and handled punt and kickoff returns for the Miners. He amassed 2,283 all-purpose yards during his career and intercepted 10 passes as a defensive back.

He also won conference championships in the low hurdles and high hurdles as a member of the Texas Western track team, which has established as a powerhouse in the Border States Conference.

NFL: New York Giants

Maynard was the final selection ninth round of the NFL Draft following his 1956 season at Texas Western. The future NFL standout actually had an opportunity to turn pro one year earlier, according to Scot Maynard, but opted to honor the commitment he had made to Texas Western and returned for one final season as a collegian.

After signing his first professional contract, he saw action in 12 games and finished with 12 rushes for 45 yards (3.8 ypc) and had five receptions for 84 yards, for a 16.8 yard average. He also played on special teams.

Despite the limited action in 1958 he became a key figure in one of the greatest games in NFL history.

On Dec. 28 Maynard and the Giants played host to the Baltimore Colts inside historic Yankee Stadium to determine the NFL champion for 1958. A 20-yard field goal off the foot of Steve Myhra with just seven seconds remaining on the clock capped a furious drive engineered by Johnny Unitas that began at the Baltimore-14 with just over two minutes to go in regulation.

Two passes from Unitas both fell incomplete, but faced with third down, he completed an 11-yard pass to halfback Lenny Moore. Another incompletion drama began to set in as Unitas completed three straight passes to Raymond Berry that covered 62 yards and moved the ball to the New York-13 to set up Myhra’s kick to tie the game and send the game to overtime.

It was the first NFL playoff game to be decided in sudden death.

Maynard took the kickoff to begin the overtime period. He muffed the kick, but was able to recover and the overtime began from the Giants 20-yard line. The Giants’ offense was unable to keep the drive going and was forced to punt and Baltimore took over at their own 20.

Baltimore moved down the field to within eight yards of the end zone. That was when someone ran onto the field and causing a delay in the game. It has been rumored it was an NBC employee who had been ordered to cause a delay because the national television feed had gone dead. It was later learned it was the result of an unplugged TV signal cable.

Whatever the reason, the delay was enough time to get the telecast back on air and set the stage for the history-making finish as Alex Ameche bowled in on third down from one yard out with 6:45 remaining in overtime to give the Colts the championship.

The game, which has become known as “The Greatest Game Ever Played,” was voted in 2019 as the best game in the first 100 years of the NFL by a panel of 66 media members.

The game is considered pivotal in the rise of the NFL’s popularity.

Unitas completed 26 of 40 passes in the game for 361 yards. Ameche rushed 14 times for 59 yards and two touchdowns in the contest.

But it was Berry who shined on the day. He caught 12 passes for 178 yards and one touchdown. His touchdown catch in the second quarter allowed Baltimore to take a 14-3 lead at halftime.

Berry’s 12 receptions was a championship game record that stood for 55 years until it was broken by Denver’s Demaryius Thomas in Super Bowl XLVIII following the 2013 season as Seattle defeated Denver 43-8.

New York was led by running back Frank Gifford who rushed 12 times for 60 yards and added three pass receptions for 14 yards and one touchdown in the game. Teammate Kyle Rote added two catches for a team-high 76 yards and Bob Schnelker added 63 yards on two catches. Quarterback Charlie Conerly completed 10 of just 14 passes for 187 yards on the day.

Maynard was released by the Giants during their 1959 training camp when he refused to shave his sideburns and forego his cowboy boots that had become a sort of trademark. He was signed to a one-year contract with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats of the Canadian Football League. He caught just one pass that season for 10 yards before returning home to Texas and taking a job as a plumber and teacher.

His time away from professional football was short-lived.

From the NFL to the AFL

With the fledgling American Football League becoming a reality Maynard became the first player to sign with the New York Titans franchise.

Vince Lombardi and Tom Landry, two of the greatest coaches in NFL history, had both been assistants with the Giants during Maynard’s rookie season. They urged Sammy Baugh, the newly appointed coach of New York’s AFL franchise to take a look at the former Giant.

Baugh, one of the greatest players in NFL history, had become familiar with Maynard after having coached against him when “Slinging Sammy” was the coach at Hardin-Simmons (1956-59) and he needed little nudging to ink Maynard to a contract.

The New York press reportedly thought little of Maynard’s return to the Big Apple. But in the end the press was proven wrong.

Maynard caught 72 passes for the Titans in his first season with the team. He and teammate Art Powell became the first tandem in professional football history to each gain over 1,000 yards in a season. The pair repeated the achievement two years later.

Over the next 13 years Maynard would achieve lofty numbers that would eventually land him a sport in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

In 1965 Maynard became teammates with a flamboyant rookie quarterback, Joe Namath, who had been the No. 1 selection in the 1965 AFL Draft after his brilliant career at Alabama.

The newly-formed tandem worked magic.

Maynard caught 68 passes for 1,218 yards that season. Fourteen of Namath’s 22 passing touchdowns in his rookie season found a home in Maynard’s hands. Two years later, in 1967, Namath passed for a record 4,007 yards and Maynard registered a career-high 1,434 yards, which led the league. He had 71 catches on the season along with 10 touchdowns and averaged 20.2 yards per catch as the Jets finished the season 8-5-1.

Maynard made history in the season opener in 1968 when he caught eight passes for 203 yards, the first game of his career with at least 200 yards. He scored two touchdowns in the game, including one that covered 57 yards in the first quarter to give the Jets the early lead. He added a 30-yard scoring catch in the second quarter as New York built a 17-3 halftime lead.

By game’s end, which New York won 20-19, Maynard had surpassed Tommy McDonald as the active leader in receiving yards. Maynard added a career-best 228 receiving yards later in the season in a 43-32 loss at Oakland.

That game is best known as Heidi Game after NBC ended its national broadcast of the game just after the Jets had taken a 32-29 lead with just over one minute left in the game. Following a quick commercial, the network showed the movie Heidi to viewers other than on the West Coast.

What most of the nation missed was the Raiders rallying on a 46-yard pass from Daryle Lamonica to Charlie Smith to put Oakland in front 36-32. The Jets fumbled the ensuing kickoff and Oakland’s Preston Ridlehuber recovered and scored to give Oakland the win.

Maynard and the Jets extracted a measure of revenge just over one month later by defeating Oakland 27-23 in the AFL Championship and sending the Jets to the Super Bowl for the first, and only time, in franchise history.

Maynard had six catches for 118 yards and two touchdowns in the game. His second score, a six-yard pass from Namath, in the fourth quarter proved to be the game-winner.

He was unable to play in the Super Bowl because of a hamstring injury suffered in the win over the Raiders and finished the 1968 season with 57 catches for 1,297 yards (22.8 ypc) and 10 touchdowns.

Despite being sidelined for Super Bowl III against Baltimore, Maynard was in on history once again.

“Dad always believed the Jets matched up well against Baltimore.” Scot Maynard said. “The Colts were like most NFL teams in that they were very vanilla on offense and very vanilla on defense.

“The Jets, meanwhile, were like the other AFL teams and had a more wide-open approach to the things they did on both sides of the ball,” the younger Maynard added.

New York coach Weeb Eubank insisted on his team watching plenty of film in preparation for the clash against the Colts. With each viewing the New York players appeared to gain more confidence in what they could do against the vaunted Baltimore squad, considered by many of the time to be among the best teams in recent NFL history.

And then the stakes grew in a big way when the flashy signal-caller from Alabama “guaranteed” a Jets victory during a luncheon just days before the big game.

“Everyone seemed to get behind (Namath),” Maynard said in recalling his father’s accounts of the game. “They all seemed to take the attitude that ‘he said it, we have to back him up.’”

The Jets won the game 16-7.

Maynard would go on to play six more seasons in the professional football. After ending his career with New York following the 1972 season he would play with the St. Louis Cardinals and spent time on the practice roster of the Los Angeles Rams in 1973. He was signed as player-coach by the Houston franchise of the World Football League in 1974. That franchise relocated to Shreveport during the season. He worked as the passing game coordinator and saw limited action on the field.

Maynard, who did not wear a chin strap on his helmet, instead used special cheek inserts that held the helmet tightly in place giving the look of being squished into the helmet.

The six-foot, 180-pound Maynard had four seasons of at least 50 catches and 1,000 yards as a member of the New York franchise. He is one of just 20 players who were in the AFL for all 10 years of the league’s existence. He is also just one of seven player who played their entire AFL career with one franchise.

Maynard was chosen first-team All-AFL in 1968 and 1969 and was a second-team selection in 1965 and 1967. He was a four-time AFL All-Star (1965, 67-69).

Hall of Fame

He finished his career as the most prolific receiver in pro football history. He recorded 633 receptions for 11,834 yards, both pro football records, and 88 touchdowns. His 18.7 yards per catch remains the highest for any player with at least 600 career receptions.

Those numbers earned him a spot in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1987.

Scot Maynard, who played college football at Texas Tech, had signed a free agent contract with the San Francisco 49ers prior to training camp that season. The 49ers and Kansas City were scheduled to play in the NFL Hall of Fame game that year creating the possibility of a memorable week in Canton, Ohio.

Jerry Rice was in his second year as the leader of the San Francisco receiving corps and the young Maynard’s chances of making the roster seemed slim. An injury made it appear even more bleak.

“(San Francisco coach) Bill Walsh told me how nice is was going to be to be able to be with my family during a very special time for us,” Scot said. “He also informed me that once I returned from the injury that I would be released.”

The young Maynard had no need to wait for his release. He accepted the inevitable that day.

“I was still able to enjoy it all with my family,” said Scot, who was an assistant coach for the CFL Winnipeg Blue Bombers in 1990. “The parade, the banquet, the induction … it is nothing but a week packed with unbelievable experiences.”

“When I was just a rookie Coach Ewbank told me, ‘Joe, you are a lucky man, you are going to be working with a great receiver. Once again, Coach Weeb Ewbank was right on the money.’” said Namath when he presented Maynard during induction ceremonies in 1987.

“Don Maynard, he was the man our opponents worried about, the knockout punch,” Namath added. “Lightening in a bottle, nitro just waiting to explode. I mean he could fly.

“The man could flat play,” Broadway Joe continued. “With the grace of a great thoroughbred, the man could flat play. He galloped through the best of the very best football players in the world.”

“After playing with 25 quarterbacks, I was sure glad I found one that started listening to what I wanted done,” Maynard quipped after being presented by Namath in Canton.

Maynard stayed true to his humble nature in concluding his hall of fame speech.

“I came to play and I came to stay,” he said with a sense of poetry. “Football was a game, Country Don was my name. I made a mark and I became a star.

“I played the best and I believe I passed the test,” he added. “I am glad this is over, I need some rest.”

Maynard, along with some of his former Jets teammates, participated in the coin toss prior to the start of Super Bowl XXXIII in honor of the 40th anniversary of the 1958 NFL Championship.

He taught math and industrial arts after retiring from pro football and sold a variety of products, including helping developing propane as an alternative fuel for school busses and delivery vehicles.

“He was an entrepreneur before there were entrepreneurs,” Scot Maynard said.

A native of Bismarck, N.D., Ray is a graduate of North Dakota State University where he began studying athletic training and served as a student trainer for several Bison teams including swimming, wrestling and baseball and was a trainer at the 1979 NCAA national track and field championship meet at the University of Illinois. Ray later worked in the sports information office at NDSU. Following his graduation from NDSU he spent five years in the sports information office at Missouri Western State University and one year in the sports information at Georgia Tech. He has nearly 40 years of writing experience as a sports editor at several newspapers and has received numerous awards for his writing over the years. A noted sports historian, Ray is currently an assistant editor at Amateur Wrestling News.