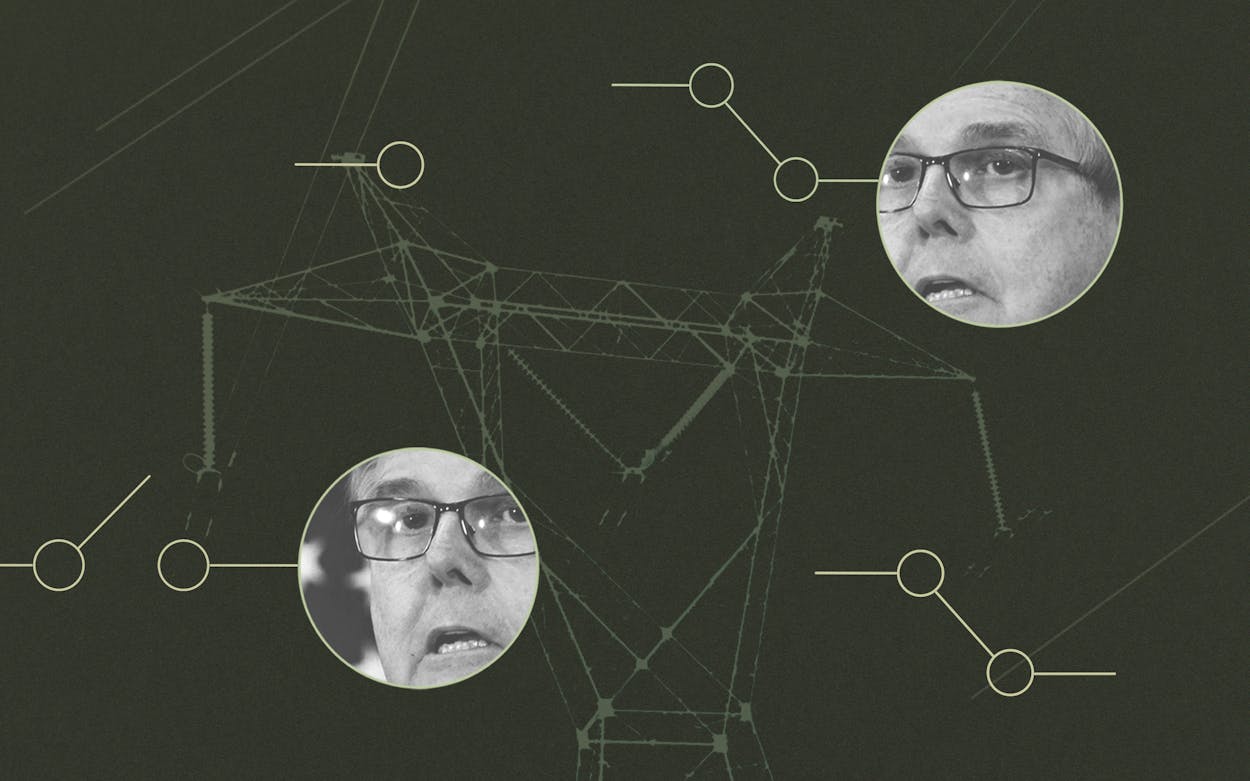

Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick stared into the TV camera at Sugar Land Regional Airport outside of Houston, barely blinking behind his thin, rectangular glasses. One week earlier, winter storms broke a long-neglected electric grid, triggering blackouts across Texas and an estimated $200 billion in damages. With power restored, Patrick had now embarked on a media tour to airports across the state—after Sugar Land, he was scheduled to hit Dallas, Abilene, Lubbock, and Midland. The lieutenant governor vowed to ensure that the millions of Texans who lost power for days would never experience prolonged blackouts again. “I personally am going to put this on my back,” Patrick said, jutting his thumb at himself, “and take responsibility for fixing it.” He leaned hard on those last two words.

The appearance was a textbook example of Patrick in times of crisis. In normal times, the lieutenant governor is most comfortable focusing on red-meat culture war issues, such as bathroom bills and demanding the Star-Spangled Banner be played before sporting events. But as Texas’s second-ranking statewide elected official, one who controls every bill that passes through the state Senate, his job often calls for him to oversee legislative responses to crises. When it does, the former radio host usually becomes a bullhorn, drawing attention to himself and the crisis, and demands private solutions to issues rather than legislative ones that conflict with his conservative worldview.

After the 2018 shooting at Santa Fe High School that left ten dead, many in the Lege called for more effective regulation of firearms. Patrick blamed the massacre on violent video games, and then bought metal detectors for the high school. When lawmakers turned their attention to the neglect and abuse of children in the state’s foster care system in 2016, the Lege allocated a bit more money for caseworkers, but Patrick mostly called upon churches and religious organizations to help recruit foster and adoptive parents.

Even after promising to fix the state’s electric grid, Patrick seemed to shift responsibility away from himself and the legislature. “Sometimes we don’t demand certain things because then they only do what we demand, they don’t do anything else,” he said, referring to the Lege’s failure to impose weatherization requirements on power generators in the aftermath of a winter storm that caused mass outages in 2011. “We’re not in the business of trying to tell everyone what to do every day.”

“If Patrick wanted to change that system, he’s had three legislative sessions to do it—really a fourth with this one,” said Mark Jones, a political science fellow at the Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University. Other lawmakers have proposed weatherization of power plants, revamping the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), the state’s main grid operator, and requiring backup energy storage—reforms that could prevent future blackouts. By contrast, the lieutenant governor has focused on a more dramatic target, directing attention to exorbitant energy bills and pointing his finger at the state’s utility regulator, the Public Utility Commission.

At issue is the commission’s management of sky-high electricity wholesale prices. The PUC gave ERCOT the okay to keep prices at the highest level the commission allows—$9,000 per megawatt hour, well above the averages of around $30 to $50—for 32 hours longer than an independent market monitor determined was necessary. (At the skyrocketed wholesale prices, a home using 2,000 kilowatt hours per month could cost a power retailer about $600 a day, as opposed to the usual $2.) According to the monitor, which recommended retroactively correcting the prices, the decision to keep rates high for those 32 hours resulted in overcharges to power companies of $16 billion, as much as $5.1 billion of which can be reallocated if the PUC orders a repricing. Doing so would save some companies from bankruptcy, and spare consumers from having the costs passed on through their power bills, perhaps for decades.

Little more than two weeks after his press tour, Patrick berated Governor Greg Abbott’s only remaining appointee on the PUC, Arthur D’Andrea, in a rare Senate committee hearing appearance. The lieutenant governor then suspended every rule he could to rush the passage of a contested plan to claw back the $5.1 billion, before encountering opposition from House Speaker Dade Phelan. Finally, after his fight seemed all but dead Tuesday evening, Texas Monthly broke news that D’Andrea had promised to try to protect the windfall of investors who made money off the blackouts. Patrick then revived his push for the House to follow the Senate’s lead and order the PUC to reprice.

Some political observers speculate the lieutenant governor, best known for his provocations—which famously include the suggestion in March 2020 that he and other seniors were willing to die from COVID to save the economy—is flexing his populist muscles in advance of a gubernatorial challenge to Abbott in 2022. Patrick denies it. Others say his position on electricity pricing is just good politics, whether he’s running for governor or not. “Dan Patrick is politically wise to use this because the upside is he can look like he’s trying to solve the problem, and there’s not much downside because people are not going to directly blame him for this,” said Brandon Rottinghaus, a political science professor at the University of Houston.

Patrick’s moves in the aftermath of last month’s blackout have helped light a fire under an otherwise sleepy legislative session hampered by COVID restrictions. Lawmakers have fewer than 75 days until they adjourn to correct problems that led to massive power outages. While bringing themselves up to speed on the difference between a kilowatt and a megawatt, they’ve wrestled with whom to blame. Some, such as representative Donna Howard, an Austin Democrat, have pointed to themselves and their fellow legislators for failing to pass preventative measures following a 2011 winter storm. Patrick, by contrast, has locked onto repricing, a solution won’t prevent future storms but is front of mind for consumers. Notably, a debate about repricing also shifts focus away from the failure of the Legislature to act after the last storm, and from debates about instilling new regulations that might make conservatives queasy.

Repricing has been likened to unscrambling an egg. Legislators are unclear which power generators and retailers and investors might come out ahead or behind from any bill, and if money might come out of the pockets of those who prepared for the storm to benefit those who didn’t. Some also worry that retroactively changing prices risks setting a precedent that the government can take back profits from companies and investors in extreme situations.

What’s more, the clock is ticking on the Legislature to pass a bill, because on March 20 contracts with power companies become settled and overcharges cannot be recouped. In some ways, this gives Patrick cover: repricing is an issue on which he can make a populist stand, while not worrying about the consequences because the odds of a bill passing the House are low. (To be sure, he’s not the only one who plays this game. During the fuss over the bathroom bill in 2017, some major campaign contributors to Abbott said that the bill would cost them millions of dollars in lost convention business. Abbott told them not to worry about the bill; then–House Speaker Joe Straus wouldn’t let it happen. And he was right.)

On March 11, Patrick began to create a spectacle over PUC repricing. Tailed by a small entourage, he showed up in the vast Senate chamber for a Jurisprudence Committee hearing at which D’Andrea, seeming unusually jolly for an energy regulator under fire, was answering questions. In his six years leading the Texas Senate, Patrick had only once before made a cameo appearance in a committee, when he had voiced support for school vouchers in 2017. Prior to the lieutenant governor’s arrival, D’Andrea had defended the decision to artificially keep energy rates high. He said the PUC ultimately didn’t want to risk another round of devastating blackouts and agreed to the rates to incentivize power companies to keep producing. He encouraged lawmakers to leave the matter alone. (No legislator knew it at the time, but by arguing against repricing, D’Andrea was keeping the private promise he had made two days earlier to big energy investors on Wall Street.)

Patrick first showered the regulator with empathy. How tough this all must be, he said to the PUC chairman, who smiled at the end of the table. “You seem like a very nice person stuck in the middle,” Patrick continued. Then the facade dropped and he proceeded to berate D’Andrea, making a scene of moralizing. “Do the right thing,” Patrick said, urging D’Andrea to order repricing. D’Andrea, bewildered and occasionally stuttering during the interrogation, refused to agree to reprice those hours of electricity, arguing that it would be illegal for him to do so.

Then, in a stunning reversal of the last few weeks of elected state leaders blaming appointed officials, the PUC chairman added that it was Patrick’s job to adjust prices, not his. “I’m not going to sit here and say I didn’t make mistakes. Obviously, we all did,” he said. “You can act. You’re the legislature. I can’t act. I’m a bureaucrat.”

Usually, Patrick does the finger-pointing, often on Fox News or a conservative radio program where the host is unlikely to challenge him. Having his bluff to take personal responsibility for fixing problems called was a new experience. Patrick went into overdrive. On Friday, March 12, he asked the governor to compel D’Andrea to change the prices. Abbott responded that night that he, like D’Andrea, thinks the PUC ordering repricing would be illegal, kicking the issue back to Patrick and the Legislature. Over the weekend, Patrick and his team drafted a bill forcing the PUC to do as it was told, and he spent Sunday night calling senators to convince them to bend the Senate’s procedural rules to take up his bill.

On Monday, the Jurisprudence Committee, which had watched Patrick dress down D’Andrea, gave the bill its blessing in three minutes with no questions. The two-page legislation passed the Senate in a little more than an hour. But unlike buying metal detectors for a school or asking churchgoers to take in foster children, passing legislation requires the approval of both houses and the governor. Patrick publicly urged Abbott to voice support for his plan, in hopes it would encourage the more hesitant House to come along. Abbott declined, and ultimately, Speaker Phelan said the House would not take up the bill.

Weeks after pointing at himself in front of cameras and saying he took responsibility for preventing future energy crises, Patrick then pointed the finger elsewhere. “The Texas Senate stood for individuals, and I’m proud of you,” he said on the Senate floor Tuesday. “The House stood for big business.” A few days later, on Thursday, Patrick assembled a press audience to hear him call out the governor. He urged Abbott to tell the PUC to stop the clock on the March 20 deadline so the Legislature can take a second hack at sorting out the repricing issue. “I’m actually coming to the governor and saying, ‘Governor, help,’” Patrick pled, adding that, otherwise, the Senate’s fix—his fix—“will be for naught.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Winter Storm 2021

- Dan Patrick