Sunrise at Aransas Bay on Texas’ central coast. Kaila Drayton/National Wildlife Federation

The quiet, resilient Mid-Coast region of Texas between Corpus Christi and Houston, which has endured vicious hurricanes and faced daunting environmental threats, is now up against its most serious foe yet: human-caused climate change. A report issued in May by the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) examines how sea-level rise, warming temperatures, storm surges, and drops in freshwater inflow are poised to assault the uniquely balanced ecosystems of the area.

According to the NWF, “Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change: An Assessment for the Texas Mid-Coast” is the most detailed analysis to date of how climate-change science from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other sources translates to specific impacts on the central Texas coast.

The Mid-Coast’s extensive wetlands, both freshwater and saltwater, are home to diverse wildlife – some officially endangered, including Kemp’s ridley sea turtles and whooping cranes. The report notes that more than half of the region’s freshwater wetlands could be lost by 2100, and more than 20% of the Mid-Coast’s land could become open water by 2100, jeopardizing many species, structures, and livelihoods.

A growing array of preservation, mitigation, and restoration funds are now available to Texas coastal areas, including set-asides in the wake of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill and 2017’s Hurricane Harvey. Yet most such assistance has gone to other parts of the Texas coast, even though the Mid-Coast has its own clear vulnerabilities.

“When we initiated this assessment over a year ago, there was no known effort underway to better understand the long-term climate-related threats the region is facing and the proactive measures that state and local leadership can be pursuing,” said Amanda Fuller, director of NWF’s Texas Coast and Water Program, in an email.

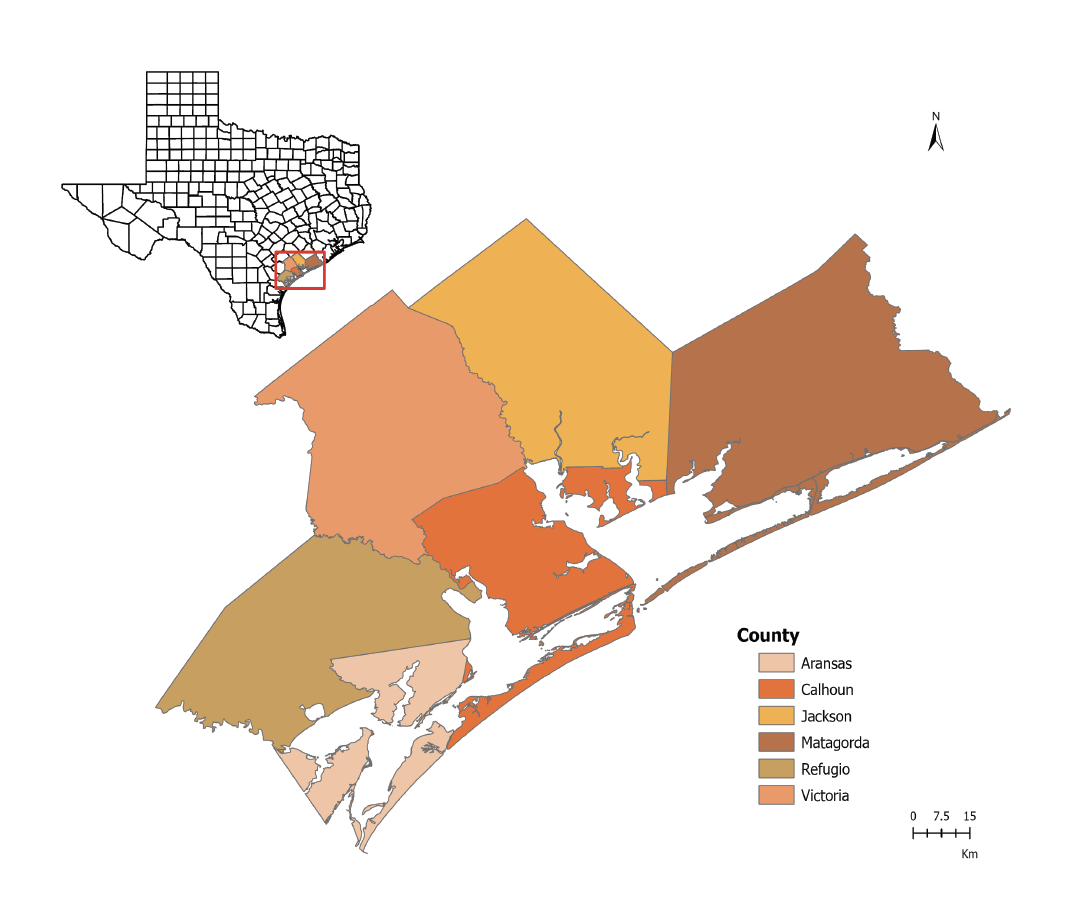

The six counties along the Mid-Coast evaluated in the NWF assessment had a combined population of just over 200,000 in 2020. National Wildlife Federation

Still endangered after all these years

One of the best-known seasonal denizens of the Mid-Coast is the whooping crane, still listed as an endangered species after decades of efforts to bring it back from the brink of extinction. Most whooping cranes – the tallest birds native to North America – winter over at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and other spots along the Mid-Coast.

The majestic bird’s population in the wild has rebounded from less than 30 around 1940 to more than 300 today. The recovery has been attributed to habitat protection and hunting restrictions in Texas and elsewhere along the whooping cranes’ primary migration corridor between the Mid-Coast and northeast Canada.

A whooping crane (Grus americana) family in their wintering grounds at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. Klaus Nigge/U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

The Aransas refuge also plays host to a wealth of other wildlife, including blue crabs, coyotes, reddish egrets, and alligators. More than 300 bird species are found in Big Boggy and San Bernard National Wildlife Refuges. All of these protected habitats are at risk of widespread inundation as the planet and the region warm and sea levels rise.

Like other parts of the northwest Gulf Coast, the Texas Mid-Coast is already being slammed by some of the world’s highest rates of sea-level rise. It’s the result of rising water levels from climate change as well as a sinking landscape, the latter mainly from extraction of oil, gas, and groundwater. The subsidence is especially dramatic in some of the bays where sea-level monitoring stations are typically located along the Texas coast.

Perched on wildlife-rich Aransas Bay just north of Corpus Christi, the small city of Rockport and its low-key charms have lured vacationers for more than a century.

In a “report card” on 2020 sea level rise at 32 U.S. sites from Maine to Alaska, the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences found that Rockport had the second-highest sea level rise (behind only Grand Isle, Louisiana) as well as the greatest acceleration. Water levels rose 7.1 millimeters (0.28 inches) at Rockport in 2020 alone. Other parts of the Mid-Coast aren’t running far behind.

Drawing on benchmark regional sea-level projections released by NOAA in 2017, the NWF report finds that even an intermediate-low scenario would see 1.71 feet of sea-level rise at Rockport by 2050 compared to 2000, and 2.82 feet by 2100. Such a rise would threaten the town’s fishing pier and beach as well as several points along the Great Texas Coastal Birding Trail.

Across the four NOAA scenarios (intermediate-low to high), the century-scale rise at Rockport ranges from around 3 to 9 feet. The difference hinges largely on how quickly greenhouse-gas emissions are cut globally.

On top of these gradual rises, there will be storm surge from hurricanes. Even “sunny day” flooding – high seasonal tides coupled with onshore flow, often during placid weather – has already increased dramatically in Texas and elsewhere on the Gulf and Atlantic coast. Such floods now occur in Rockport on an average of seven days per year, compared to an average of just once per year in 2000. By 2050, based on NOAA projections, the town can expect between 60 and 160 high-tide flood days per year.

Live oaks are among the grandest and most resilient parts of Mid-Coast landscapes. The famous “Big Tree” at Goose Island State Park north of Rockport is estimated to be more than 1000 years old – surviving Harvey and many previous hurricanes – and has a trunk circumference of more than 35 feet. (Larry D. Moore / Wikimedia Commons)

What happens when the sea sweeps in and the rivers dry up?

Although the NOAA sea-level projections used in the NWF reports are adjusted for local topography, John Anderson, a professor emeritus of oceanography and sea-level-rise expert at Rice University, points to important processes beyond basic inundation (a given increment of sea-level rise by a certain date at a certain point).

Barrier islands and wetlands are dynamic features that respond in variegated ways to a rising sea level, Anderson notes. And subsidence rates can vary markedly across short distances based on the underlying geography, he adds. “I do think there is need for concern about future impacts of sea-level rise in Texas,” Anderson said in an email.

Most of Texas’ barrier islands are retreating landward, while coastal marshes are building upward. However, these natural responses have their limits, and they hinge on a continuous supply of sand and sediment. That’s one reason why freshwater inflow is so crucial to the Mid-Coast’s future. And freshwater is a particular Achilles’ heel for the region.

The precipitation contrasts for which Texas is notorious, from the lush, moist east to the parched west, get concentrated as they translate into river flows converging on the Gulf Coast. Typically, there’s more than enough water flowing to the upper Texas coast to compensate for evaporation. Meanwhile, the lower coast is accustomed to sparse inflows that lead to a hyper-saline coastal environment.

In between, the Mid-Coast is especially prone to erratic ups and downs in freshwater inflow from both natural and human causes.

Events such as the unprecedentedly hot, dry summer of 2011 are already leading to sharp year-to-year variations in Mid-Coast River flow. A boost in hydrologic extremes is one of the well-documented consequences of climate change. Upstream demands from a growing population, especially in the Austin-San Antonio area, could make the dry river years even worse for the Mid-Coast.

In its recommendations, the NWF assessment calls on state policymakers to leverage a law passed by the Texas Legislature in 2007, Senate Bill 3, to assess and protect the flow levels needed to ensure the health of Mid-Coast ecosystems as climate change unfolds. The 2019 Texas Coastal Resiliency Master Plan recommends more than 25 Mid-Coast projects that could total more than $170 million.

Community-based resilience efforts will be crucial as well. Even an intermediate-low sea-level rise will threaten dozens of police departments, city halls, and other facilities, according to the NWF report.

According to biologist Larry McKinney, Harte Research Institute chair for Gulf strategies at Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi, “the [Mid-Coast] has not gotten the attention or the resources that it deserves compared to the upper coast.” Having worked with local stakeholders for decades, McKinney finds that many are skilled and dedicated, “but the same person may also be both the mayor and fire chief. They just don’t have the time or expertise that the Houstons and others have.”

With this report, says McKinney (who was not involved with the study), “as people put grants together and decide priorities, they have this complex science brought together in a way they can use.”

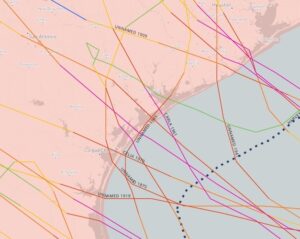

Major hurricanes (Category 3 or stronger) that made landfall along the central Texas coast between 1851 and 2020. The unlabeled purple line at center denotes the catastrophic 1886 hurricane that left Indianola a ghost town. NOAA Historical Hurricane Tracks

Then there’s hurricanes

The NWF report arrives as parts of the Mid-Coast are still licking their wounds from 2017’s devastating Hurricane Harvey. After two years of rebuilding, the region was looking forward to a more normal tourist season in 2020 only to be set back once again, this time by the Covid pandemic.

Harvey’s biggest human and fiscal toll came from titanic post-landfall flooding across southeast Texas and far southwest Louisiana. However, the 132-mph sustained winds of Harvey’s Category 4 landfall near Rockport left a shredded landscape and major structural damage on parts of the Mid-Coast. By early 2018, nearly as much debris had been hauled away from Rockport (population about 10,000) as from Houston (metro population 7 million).

Harvey’s rapid spin-up allowed little time for a major storm surge to build. Still, inundation from Harvey (storm surge plus tidal levels) reached as high as 10 feet in San Antonio Bay.

The normal year-to-year vagaries of hurricane season are now being boosted by warmer oceans, which raise the odds that a given hurricane can rocket to fearsome strengths. There’s also research suggesting that Atlantic hurricanes are intensifying more rapidly in a human-warmed climate. “The damage potential of these hurricanes will further increase with a potential rise in sea level,” warns the NWF report.

The state’s Coastal Resiliency Master Plan focuses on risks from a Category 2 hurricane. However, this “does not adequately reflect the future surge conditions,” according to the NWF.

Even without considering climate change, history is enough to give the Mid-Coast pause. In 1961, Carla struck near Matagorda Bay as a strong Category 4 hurricane. The storm killed 46 people and inundated large parts of the Mid-Coast, with a storm surge of 22 feet at Port Lavaca.

On the west side of Matagorda Bay, Indianola – among the most vibrant settlements on the Texas coast following the Civil War – was assaulted by a pair of catastrophic hurricanes in 1875 and 1886, leaving the community a ghost town. In a watery irony, the NWF report notes that a local sea-level rise of three feet would be enough to inundate the historic Indianola cemetery – a resting place for hurricane victims, but one that may not prove as permanent as their families once hoped.

Bob Henson is a contributing editor of Texas Climate News. A meteorologist and science writer based in Colorado, Henson is the author of “The Thinking Person’s Guide to Climate Change.”