In 2001, I took a tour of Rice University with a group of fellow prospective students. Our undergraduate guide, briskly walking backwards through the idyllic, tree-shaded campus, pointed out all the qualities that made Rice different from the other colleges we might be considering: the residential college system, the small class sizes, and Baker 13 (don’t ask). At Rice, we were told, undergraduates were entrusted with extraordinary responsibility. Students administered the Honor Code, helped run the residential colleges, managed the coffeehouse, and had full control over the campus’s 24-hour radio station, KTRU.

Boasting a 50,000-watt transmitter, KTRU was one of the country’s most powerful college stations, broadcasting proudly eclectic music all across the sprawl of Houston. After matriculating at Rice in 2003—I transferred from Boston College after my freshman year, refusing to endure another New England winter—I signed up for an hour-long DJ shift between 4 and 5 a.m. on Saturdays. I made it through one bleary-eyed set before quitting, but many of my friends stuck it out, eventually graduating to prime-time spots in the lineup. My roommate hosted a show devoted to post-punk music every Tuesday evening for several years. For him and many others, working at KTRU was among the best of their Rice experiences.

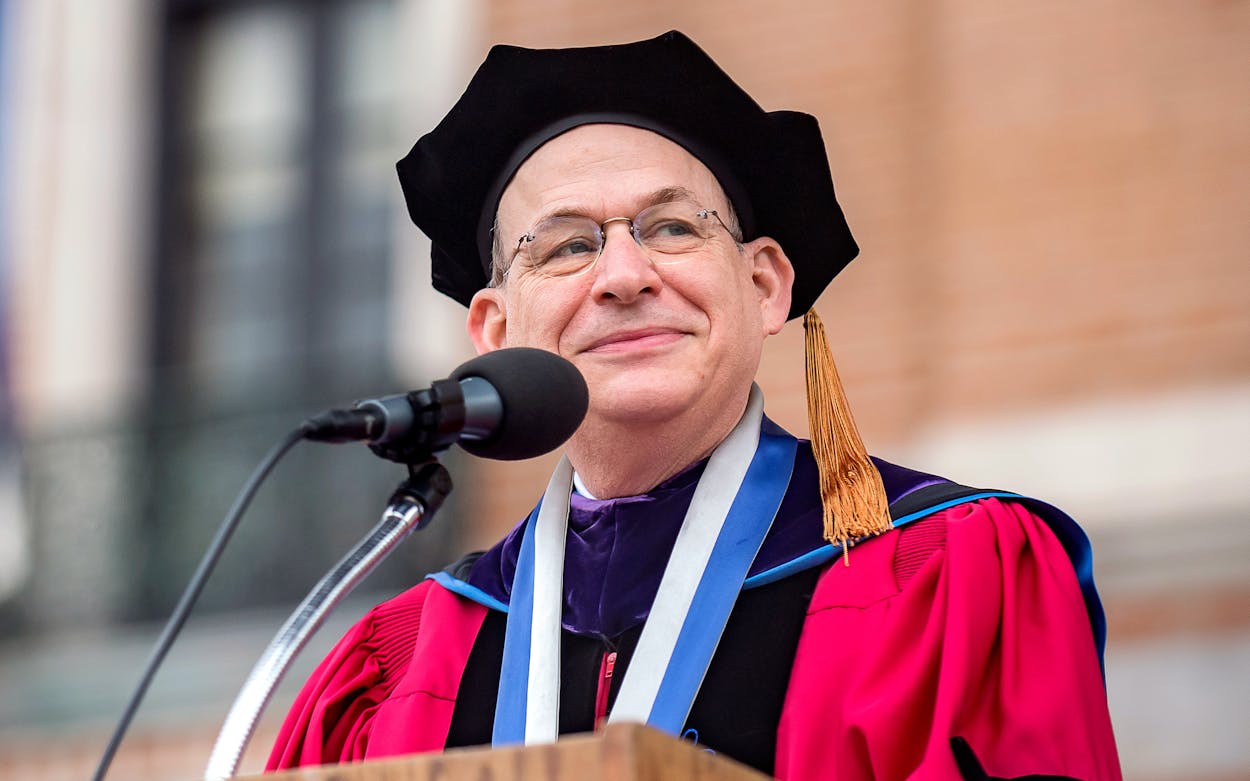

I thought a lot about KTRU when Rice president David Leebron announced his retirement last month after eighteen years as president, the second-longest tenure in university history. In 2011, with the approval of the Rice board of trustees, Leebron sold KTRU’s tower, frequency, and license to the University of Houston for $9.5 million. He argued that, given the station’s modest audience, the money would be better used to finance a new food service facility and other campus amenities. The move infuriated some alumni. “I didn’t think it was his to sell,” said Mark Stoll, who graduated in 1977 and now teaches history at Texas Tech. “It was a labor of love, run by students and managed by students.” Joey Yang, the undergraduate station manager at the time of the sale, helped organize a letter-writing campaign by KTRU veterans urging Leebron to stop the sale. “It was painful, especially for the hundreds of students and community volunteers who put in time to create a twenty-four-seven DJ schedule, only for the university to turn around and say, ‘Oh, this is an underutilized asset.’”

In almost every measurable respect, Rice is a better university now than when Leebron took office in 2004. News coverage of Leebron’s retirement has reflected this, highlighting some impressive statistics. Under his watch undergraduate applications grew from 8,100 to 30,000, research awards from $72 million to $173 million, the university endowment from $3.3 billion to $7 billion, and the annual budget from $334 million to $800 million. Thanks to a major capital campaign and Leebron’s fund-raising prowess, Rice undertook a $1.8 billion campus expansion that added dozens of new buildings, including two new residential colleges. (Texas Monthly owner Randa Duncan Williams, a Rice graduate, sits on the board of directors of the Rice Management Company and the board of trustees of Rice University.)

But for some alumni, faculty, and community members—whose voices have largely been absent from press coverage of Leebron’s retirement—the university’s extraordinary growth has come at the expense of some of the distinctions that made Rice special. Melissa Kean, who served as Rice’s official historian from 2005 to 2020 and led the search committee that hired Leebron, told me that the president had been a transformative leader. “But you don’t get that kind of growth without some trade-offs,” she conceded. “And there have been some cultural trade-offs that have been made.”

Some of those trade-offs have been for the best. Leebron helped rein in Rice’s out-of-control undergraduate drinking culture by instituting a partial ban on hard alcohol after ten students were hospitalized for alcohol poisoning in 2012 during the annual Night of Decadence party. Leebron also forged better connections between the university and Houston, challenging Rice’s “inside the hedges” mentality with programs such as the Passport to Houston, which provides students free admission to many of the city’s cultural institutions such as the Museum of Fine Arts, the Museum of Natural Science, and the Houston Zoo. He also provided more funding and prominence for the visual arts by launching a public art program, building the Moody Center for the Arts, and announcing plans for a new building for the chronically neglected Department of Visual and Dramatic Arts.

Most important, Leebron made the student body more diverse and more international. In 2004, when he became president, Black students made up 7 percent of the undergraduate body in a state that was 13 percent African American; by 2020, they made up 11 percent. During that same period, Hispanic representation increased from 12 percent to 17 percent and Asian American representation from 14 percent to 31 percent. Leebron also oversaw a boom in international students, who went from just 3 percent of undergraduates to 12 percent. If you include master’s and doctoral candidates, fully a quarter of Rice students now hail from another country.

In 2018, the university rolled out a new financial aid program program called the Rice Investment. Under the program, admitted students with families earning as much as $65,000 receive free tuition, room, and board; students from families making between $65,000 to $130,000 pay no tuition; and those with family incomes between $130,000 and $200,000 receive half-tuition scholarships. That sounds generous—and it is. But as I wrote for Texas Monthly at the time, Rice was playing catch-up with the elite private schools it considers its peers. Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, Yale, and the like all have well-established financial aid programs, many of them significantly more generous than Rice’s.

It’s unclear whether Rice is substantially more affordable now than it was in past decades. From its opening in 1912 to 1965, the university charged no tuition at all, as stipulated in its charter (written at a time when attendance was limited to white Texans). The cost of attending Rice for the 2021–2022 year will be $71,745, although only students from the wealthiest families pay full price. The best measure of college affordability is average annual cost—tuition, living expenses, books, and supplies, minus the average financial aid package. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, Rice’s average net cost was $19,215 for the 2019–2020 school year—down from $23,435 (in inflation-adjusted dollars) in 2006–2007, toward the beginning of Leebron’s tenure. Rice’s current net cost makes it more affordable than Brown, Columbia, Duke, and the University of Chicago, but more expensive than Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, and Yale.

While Rice offers need-blind admission to American students, meaning that family income isn’t a factor in admissions, international students are explicitly excluded from the Rice Investment. According to Rice, only 22 percent of foreign students receive any financial aid. “That means we can only accept international students from very affluent families,” Moshe Vardi, the Karen Ostrum George Distinguished Service Professor in Computational Engineering, told me. Further, as Leebron told me last week, about half of the international students come from a single country: China. “Don’t get me wrong, we get fantastic international students,” Vardi said, “but the fact that [about half] of our international students are coming from a single country is a concern, I believe.”

Leebron said his decision to dramatically increase international admissions was an effort to make Rice more diverse and globally oriented and had nothing to do with money. He told me he hopes the school can broaden the pool of international students it can support. “One of the things I was not able to do that I hope my successor will be able to do is find ways to fund more financial aid for international students,” Leebron said. He also noted that Rice isn’t alone in its high proportion of Chinese students—China has long sent more students to U.S. colleges than any other country, accounting for about a third of America’s international students.

When it comes to improving town-gown relations, Leebron’s record is mixed. Although he’s encouraged more students to get involved in cultural and volunteer activities around Houston, he’s also overseen an expansion of Rice’s physical footprint in the city against the wishes of some residents. The most high-profile example is the Ion, a 266,000-square-foot “innovation hub” in Houston’s Third Ward, a predominantly Black neighborhood near downtown and a mile and a half from Rice. Built in a former Sears store, Ion is intended to support technology start-ups and entrepreneurship. It anchors a sixteen-acre “innovation district” on land that Rice owns. The Rice Management Company, which oversees the university’s endowment and spearheaded the Ion development, appointed a group of business and civic leaders to advise it on community relations before breaking ground on the center. “The Rice Management Company had many community conversations, and they were in close touch with the mayor and the mayor’s staff,” Leebron told me.

Nonetheless, some community organizations fear the development will raise property values and therefore property taxes, and push out longtime residents and businesses. “When you bring in that kind of capital in a city that has no land-use protections, we don’t have any way to protect our historic landmarks and institutions,” said Assata Richards, a Third Ward resident and director of the Sankofa Research Institute, which conducts research and advocates on behalf of the community. Among the landmarks Richards worries about are Riverside Hospital, the Shape Community Center, and Trinity United Methodist Church. April saw the demolition of the Sixth Church of Christ, Scientist, a historically African American church founded in 1914 in the Third Ward.

Leebron has also been accused of neglecting elements of Rice’s history. Although Rice built its reputation on science and engineering, it also has a rich cultural legacy, thanks largely to Houston art patrons Dominique and John de Menil. In 1969, after clashing with the nearby University of St. Thomas, the Menils shifted their support to Rice, bringing along their handpicked art historians and studio art teachers. The Menils commissioned the so-called Art Barn, a corrugated-steel building on the south side of campus, where they hosted major exhibitions and film screenings by Bernardo Bertolucci, Roberto Rossellini, and Andy Warhol. The Menils eventually left Rice to build the Menil Collection, leaving behind the Art Barn, which was converted into classroom space for Rice’s continuing education program.

In 2014, rejecting pleas from preservationists, Leebron tore down the building, which had been designed by prominent architect Howard Barnstone and helped spark Houston’s “tin house” movement. Sarah Whiting, then the dean of Rice’s architecture school, supported the demolition, telling me that the Art Barn was “not in good shape” and “wasn’t built [to last] one hundred years.” But some alumni and architects were appalled, launching an unsuccessful preservation campaign that caught the notice of the New York Times. Today Leebron dismisses such concerns, telling me that the Art Barn “occupied very scarce space on campus” and that a university art panel concluded it “didn’t have the kind of historical significance that folks claimed.” Rice plans to build the new Visual and Dramatic Arts building on the Art Barn’s former site, but the notion that the university is short on space might seem laughable to anyone who’s set foot on the low-density, three-hundred-acre campus; if he wanted, Leebron could easily have built the new arts building somewhere else.

Leebron makes few apologies for his tenure, which will formally end in spring 2022. (A search is under way for his successor.) “When I became dean of the Columbia Law School, somebody said to me, ‘If you get out of this job not having made anybody unhappy, you haven’t done your job,’” he said. In 2013, Leebron attempted a rapprochement with KTRU by working a set as a DJ. By then, KTRU had become an Internet-only station. (In 2015 it acquired a low-power transmitter that projects its signal only to the Rice campus and surrounding neighborhoods.) The difference between an online and a terrestrial station was illustrated during Leebron’s set when the Internet connection crashed for several minutes. Many listeners made note of Leebron’s tongue-in-cheek song selections, which included two versions of “Money (That’s What I Want).” But perhaps his most telling choice was Edith Piaf’s classic torch song “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien.” As Leebron informed listeners during a song break, that’s French for “No, I Don’t Regret Anything.”

- More About:

- Rice University

- Higher Education

- Houston