by Mark Harvey

Photo by Julia Culp

In the spring of 2018, Earl Cooper noticed that the wild horses roaming on the desert where he lived were suffering terribly from the ongoing drought in eastern Utah. The springs where they watered were drying up and there was very little grass with the lack of moisture. On his forays into the desert, he came across horses too weak to stand up and some that had already succumbed to starvation and thirst.

Cooper was a white man who had been living on the Navajo Nation near Monument Valley for about 25 years. From a young age, he had been obsessed with horses, and his home in the Utah desert afforded him endless opportunities to ride for miles and miles with distant horizons of vermilion cliffs and canyons.

On his rides, he could see the two rocky lobes that defined the Bears Ears 40 miles to the north and he could see Navajo Mountain, known to the tribe as Naatsisʼáán, 40 miles to the south. And there were the bands of wild horses roaming the country, sometimes curiously approaching Cooper and sometimes gliding away from him at a graceful lope over the rugged terrain.

Cooper had found companionship with horses nearly his entire life. “There’s a feeling you get with them,” he says. “It’s a camaraderie. Horses are our best friends and helped us pioneer the west.”

So that spring as he saw more and more horses where he lived suffering, he said to himself, “I gotta do something. If I don’t, no one will.”

The area where Cooper lives is so dry that he does not even have a well or spring for his own domestic water. He fills large tanks at a community well 20 miles from his house.

Cooper is not a rich man and really his best asset at the time was a good truck and a strong desire to help the horses. With the help of some friends, he acquired five large plastic water tanks (each of which could hold a few hundred gallons) and a flatbed trailer to haul the tanks. Then he began a daily routine of driving to the community well at 3 a.m., filling the tanks, going home, getting a few hours rest, and then hauling the tanks out to the country where the horses roamed. He did the 3 a.m. routine to avoid waiting in line at the well and also to avoid unwanted attention. On the Navajo nation, sentiments were mixed about how to deal with the wild horses, ranging from supporting Cooper to resenting him for taking water that some thought was needed for livestock and human use.

At first the horses were too shy to approach the tanks, but soon they began to drink from them and became accustomed to Cooper’s routine. When he took water out to them in the darkness of the early morning or the late evening, they would approach him with snorts and a desperation from their thirst.

Cooper began to bring hay too. He would use the same donated trailer to haul hay out into the desert and the horses would eat it as fast as he could deliver it.

Over the weeks and months, Cooper thought he saw some improvement in the condition of the various bands but he also continued to encounter horses too weak to get on their feet. To end their suffering and to prevent the horses from being eaten alive by predators, Cooper put down seven horses over the course of a few months with his pistol. But first he would try a last-ditch effort to revive them. He would bring them pails of water and set them down close enough to drink. Then he’d wait a day. If the horse still couldn’t get on its feet, he would shoot it.

“That was hard on me,” Cooper says. “But dying of thirst is a horrible death—it’s a slow death.” (Earl Cooper is a pseudonym as the real person does not wish to be identified.)

The history of wild horses in America began with the Spanish in the late 1600s as they settled the southwest around what is now New Mexico. In those days, the horse was the fastest form of transportation and a terrible instrument of war. A few men on horses could dominate vastly superior numbers of men on foot.

In his excellent book, Wild Horse Country, David Phillips describes the power the horse gave the Spaniards as they invaded North America:

Hernán Cortés landed in Mexico in 1519 with five hundred men and just sixteen horses. When his men came riding four abreast into the capital, Tenochtitlan, which was built on a great lake, canoes came paddling from every corner so people could gape at the monsters, who seemed to be half-human, half-deer, and able to come apart. The Spanish quickly realized the horse was their secret weapon….

So important to the Spaniards’ conquest of the southwest United States were the horses that they forbade Indians from owning or riding them. When one reads about the strict control and the harsh penalties the Spaniards dealt Indians who stole horses, the word used by statesmen after nuclear weapons were invented comes to mind: non-proliferation.

Phillips identifies 1680, the year Pueblo Indians rose up and rebelled against the Spaniards near what is today Santa Fe, New Mexico, as the real beginning of wild horses on the North American continent. On August 10, 1680, after much planning, and secret communication, Pueblo Indians stole hundreds of horses, sealed the roads, and attacked the Spanish settlements. Some 400 people were killed in the raids and the Spanish forever lost control of horses in North America.

The spread of horses among Indian tribes was fast and furious. They quickly became superb horsemen and after a few generations, the horse was woven into their art and culture. Phillips elegantly describes the newfound power horses gave Native Americans:

Looking back through the centuries, there may be no way to fully appreciate what horses meant to the tribes, or how potent was the thrill of looking into a horse’s eyes, feeling its hot breath, and realizing its strength could be your strength, its speed your speed. A horse and rider could be inestimably more than the sum of their parts. For the tribes, it was everything. The distance and space in the West that had been once oppressive and impoverishing suddenly could become a source of power. Vast grasslands that had been deserts could be turned into muscle, speed, wealth, and weapons of war that, in the right hands, could turn bands of meager scroungers into a fighting force powerful enough to terrorize modern empires and keep both the Spanish and the American armies at bay.

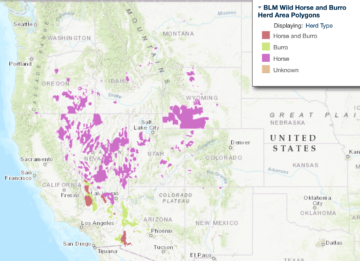

Today about 86,000 wild horses roam the American west in ten western states. They require vast, unfenced terrain, a certain amount of grass, a little water, and not much else. So wild horses live in what are described as the “badlands,” places not much good for anything but sparse grazing, mining when the minerals are there, and sometimes military training grounds or bombing ranges.

Over millions of years of their evolution, horses developed a digestive system that allows them to eat and survive on very low-grade vegetation that other animals, including cattle, don’t digest well. There is an overlay between what horses and cattle eat, but because of their cecal digestive system, horses can take energy from plants with high cellulose content when ruminant ungulates can’t. Thus a horse can keep a healthy body weight in ranges with very poor grass.

To many, wild horses are the symbol of the American West and with their scrappy ways, fleet travel on hard hooves, toughness, and self-sufficiency, represent what many Americans wish to see in themselves. So important to the American psyche are wild horses that in 1971, Congress passed, and then President Nixon signed, The Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act.

The preamble to the act reads, “Congress finds and declares that wild free-roaming horses and burros are living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West; that they contribute to the diversity of life forms within the Nation and enrich the lives of the American people; and that these horses and burros are fast disappearing from the American scene. It is the policy of Congress that wild free-roaming horses and burros shall be protected from capture, branding, harassment, or death; and to accomplish this they are to be considered in the area where presently found, as an integral part of the natural system of the public lands.”

The act that on paper set out to protect wild horses on public lands, but within the bounds of an ecological balance, has led to a fifty-year debate among horse lovers, cattlemen, conservationists, biologists, and hundreds of other sundry groups consumed by the issue.

The fundamental issues revolve around how many horses the land can sustain, where they should live, how to control the populations, what is and isn’t humane treatment, and what to do with those removed from federal lands.

The conversation about how to manage wild horses across our vast western lands becomes shrill, hot, and lathered in a hurry. Horse people, as a breed, are—in my experience—very sure of their opinions. Whether it’s choosing a horse at auction, the proper bit, or even the proper bride, most horse people trot out their opinions with such confidence and lack of doubt that one has to assume they were breastfed far too long into their development. Few are the times you’ll meet a zealous equestrian who will say, “I don’t know, what do you think about the subject?”

But the wild horse issue with all its complexity, overlapping bureaucracies, competing parties, and scarce natural resources is what economists call a “wicked problem.” A wicked problem has no perfectly good solutions, has many stakeholders with wildly differing opinions, and is not time-bound. In short, there is no clear black-and-white answer, there is no framing it with true or false. There is certainly none of that rosy-cheeked win-win or “expanding the pie” as those in the negotiations trade say. Examples of wicked problems include what to do about poverty or the homeless. Wicked problems are often zero-sum games.

The dire condition of horses that Earl Cooper experienced on the eastern Utah desert is at the extreme end of the spectrum. Tens of thousands of other wild horses roam the badlands with enough food and water to sustain them in rude health with glossy coats and fleshy bodies. In my days on horseback, I’ve run into hundreds of horses in Wyoming’s Red Desert and on parts of the Colorado Plateau that have a robust carriage and vigor that would be the envy of any equestrian. That they can maintain themselves on lands with so little forage, reminds us of why they are such a powerful symbol in our mythology.

Most wild horses live on lands managed by The Bureau of Land Management on what are titled Herd Management Areas. Under its charter, the BLM manages its lands for “multi-use” which might include livestock grazing, recreation, mining, and wildlife. It’s left to the BLM to determine the appropriate number of horses per herd management area and then to remove horses through “gathers” if they determine there are too many horses for the range to sustain.

There are 177 herd management areas in 10 states. Nevada, with nearly half the population, has by far the most wild horses of any state. Wyoming is a distant second with about a sixth the number of horses as Nevada.

According to Jenny Lesieutre, Public Affairs Specialist for the BLM’s Nevada Wild Horse and Burro Program, the BLM does extensive environmental assessments with 30-day public comment periods before doing gathers. Lesieutre says that if horses are left to breed and roam without active management, they quickly overpopulate, overgraze, and destroy natural springs.

“If a horse runs out of water it can die within 24 to 48 hours,” Lesieutre says. “But it can take a horse a year to starve to death.”

There are dozens of activist groups and thousands if not millions of people who disagree with the BLM’s management practices. Some say the BLM is far too accommodating of the cattle and sheep industry and that they unnecessarily remove otherwise healthy horses from the range to allow for better livestock grazing.

For instance, a group called Equine Advocates states on their website, “Today there are approximately 50,000 wild horses who have been violently rounded up by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) living in government holding facilities. All these horses are being held needlessly at the taxpayers’ expense. There are humane ways to manage them on the ranges at half the cost to the American taxpayers than the cost of the round-ups that are both cruel and completely unnecessary.”

Yet another stakeholder in this wicked problem is the conservation community. Because wild horses roam the chaparral where sagebrush live, some scientists say their overabundance threatens the endangered sage grouse. In a recent article in The Journal of Wildlife Management, authors from the United States Geological Survey say there is a direct correlation between too many wild horses and declines in sage grouse populations. Advocates for the wild horses would challenge that by saying that cattle allotments on BLM land are equally destructive to imperiled species, so why not remove the cattle.

The BLM has target numbers for every herd management area known in its documentation as Appropriate Management Levels (AMLs). The agency estimates that the AML nationwide is for about 27,000 horses, less than a third of the number currently roaming the west.

So every year the BLM gathers thousands of horses in pens after their staff determines that the area is overpopulated. The horses that are gathered really have two destinies: adoption by private parties or being shipped to live out their lives on farms, ranches, and other holding facilities maintained by the BLM. Little did the authors of the 1971 Wild Horse Act know that fifty years after the act was passed that the BLM would be holding, feeding, and maintaining close to 50,000 horses at ranches and farms across the country. The majority are kept on ranches in the great plains states such as Oklahoma and Kansas and the costs are astronomical. In 2020, the BLM spent $56 million maintaining the gathered horses, nearly 60% of its entire wild horse program budget.

Wild horses are adopted and trained by some people but the adoption numbers are dwarfed by the total number removed from the range. For instance, in 2020, 4,741 horses and burros (combined) were adopted but 10,824 horses and burros (combined) were removed from federal land. Presumably, that means the BLM will have another 6,083 animals to maintain at their farms and ranches across the great plains.

According to Lesieutre, in the 1980s, the ratio of adopted horses to horses removed was the opposite: more horses were adopted than were removed. She says part of the difference is due to a changing American culture. “Society has changed,” she says. “In the 1980s there were more ranch kids. Kids were riding horses back then, now they’re riding technology.”

Adopting a wild horse is not to be done without some careful consideration and certainly not without some skills and experience. But many experienced horse trainers, professional and amateur, have done remarkable things with their adopted horses. Bobby Kerr is a prime example.

When Kerr was 14 years old, he ran away from his home in the Canadian province of Ontario to go be a horse trainer in Illinois with Cletus Hulling Quarter horses. He had to lie about his age to get a job as the Hullings only hired you if you were at least 16. When he arrived in Illinois, he sent his parent a postcard and they immediately drove 850 miles from Ontario to fetch him and bring him back to Canada. Once at home, he told his parents, “You better watch me like a hawk, ‘cause I’m going back there to be a horse trainer.”

Kerr convinced his parents that his dream was worth pursuing and when he was still in ninth grade, they drove him to Niagara Falls, where he got on a bus for the Cletus Hulling Quarter Horse training center and a lifetime of training horses.

In 2010, a friend of Kerr’s invited him to attend the Mustang Makeover contest in which contestants choose a wild horse from a BLM auction and then are given just 120 days to train it for a competition. Kerr demurred but his friend bought two tickets and said, “You’re going.”

Kerr was bedazzled by how well trained the mustangs were in such a short time. He decided to enter the contest himself in 2011 and was sent a video of about 200 mustangs that would be auctioned in the spring. The video only had about 15 seconds of footage per horse so there was little to study. But Kerr studied the video all winter and came up with a short list of horses he wanted to bid on in April. He won the bid for one mare and one gelding.

Kerr had never seen the horses he bought in the flesh, only on the video, and when he showed up at the stock pens to pick up his two purchases he realized that the gelding presented to him was not the one he saw on the video. “The horse they gave me had the mane of the wrong side, a white pastern on the wrong side, and a short tail,” he says. “When I told them that it was the wrong horse, they said, ‘you know you’re right, you can have him for free.’” Kerr took the two horses home and quickly fell in love with the free gelding.

Over the next 120 days he worked and trained the two horses intensely and his first year in the Mustang Makeover competition, he won 4th and 5th place with the gelding and mare respectively for a total prize-winning of $15 thousand. He was hooked.

The following year, he entered the auction and the Mustang Makeover competition again and bought a wild horse for $1,500. When he brought the horse home he realized that it could kick like hell. “He had a whale of a round-house kick,” Kerr says. “He didn’t like anything behind him and when I dragged a tarp behind him to get him used to tarps, he got on his knees and tried to kill it like it was a coyote. I named him May-Pop because you just didn’t know—he may pop you.”

But Kerr stuck with May-Pop and patiently calmed him down. And he had a plan. He bought an old car of 1930s vintage, cut the roof off, and taught May Pop to feel comfortable with the car. He also brought May-Pop under the saddle and got him to respond to light cues. On the day of the competition, Kerr rode out into the arena dragging the car with a rope from his saddle. After loping May-Pop around the arena, wheeling him in a tight circle, and riding him without a bridle, (all impressive enough after just 120 days of training) Kerr rode the horse into the car, got it to sit down in the passenger side, and then the two of them drove off together to the utter delight of the crowd. Quite possibly Kerr had outdone his childhood hero, Roy Rogers, on a $1,500 wild horse.

Kerr went on to win the Mustang Makeover again in 2020, and has developed a very popular roadshow demonstrating the potential of adopted mustangs. “I gave up everything else and gambled that I was gonna do good,” Kerr says.

The passion and attachment to wild horses that both Kerr and Cooper have along with the countervailing beliefs about wild horses help explain the difficulty in solving a problem that stirs the passion of millions and eats up about $100 million per year of federal funds.

Some suggest that horses removed from the range should be harvested for human consumption or to feed zoo animals (horse meat seems to be a favorite for wild animals in captivity). Our Canadian neighbors to the north happily dine on horse meat. For instance, a restaurant in Montreal called Lustducru that gets very positive reviews on TripAdvisor offers Bavette de cheval, pois frais aux champignons, purée de pommes de terre à la fleur d’ail, bacon, for $28 Canadian. Roughly translated, that’s horse flank steak, fresh peas and mushrooms, mashed potatoes with garlic scapes and bacon.

One horse owner I spoke to (who asked to remain anonymous) suggested that excess horses could help solve the humanitarian problem of starvation. “When you go into a poor country and see people starving to death and we have a commodity that could be helping human beings…well, that’s an integrity question for people to dig deep and ask themselves,” she says. “But we have a very strong emotional tie to animals we all love.”

Eating a horse in the United States is as taboo as eating a dog. Americans happily spend about $30 billion on pet food every year, much of it produced with beef. It’s safe to say that the less desirable parts of several hundred thousand cattle (if not a few million) are consumed by our dogs each year. Some of those same cattle share rangeland with wild horses. An alien with no knowledge of our history and attachment to horses might wonder how a person who feeds his dog in the morning with beef can fret about the treatment of distant horses in the afternoon. A wicked problem indeed.

This week the BLM will be doing an “emergency wild horse gather” of about 2,200 horses on The Antelope Complex, 50 miles southeast of Elko, Nevada. The press release announcing the gather states in part, “The purpose of the gather is to prevent undue or unnecessary degradation of the public lands associated with excess wild horses, to restore a thriving natural ecological balance and multiple-use relationship on public lands. By balancing herd size with what the land can support, the BLM aims to protect habitat for other wildlife species such as sage grouse, pronghorn antelope, mule deer, and elk.”

Surely the gather will please some—those who think there are too many horses doing too much damage in that part of Nevada—and it will infuriate others—those who think the wild horses deserve greater range, that the gathers are inhumane, or who believe there are better ways to control their populations.

But the wild horse issue has all the markings of a wicked problem that cannot, and will not be solved by what Rice University professor Eric Dane calls “cognitive entrenchment”: approaching the same problem with the same thinking. Fresh thinking would require all the interested parties to take a fresh view, which is very hard for human beings to do. Even then it is unlikely that all the issues would be solved to anyone’s liking.

In the meantime, some evening driving or hiking through the badlands of Utah, Nevada, or Wyoming you may chance upon a band of wild horses loping across the desert and feel the same thrill that Indians felt when the Pueblo people liberated the horses from the Spaniards in 1680. And the feeling may consume you and take your life on some unexpected path as it did Earl Cooper and Bobby Kerr. If it does, grab your hat, ride like hell, and stay on!