After Larry McMurtry died in March, there were the expected obituaries and online outpourings of appreciation from readers, but there was no funeral, no memorial service, no opportunity for public homage. “He was an atheist,” McMurtry’s great friend and writing partner Diana Ossana told me, “and felt that life should be lived as it occurred, rather than celebrated after death.”

Fair enough, and clear enough. But there was still that sense of a withheld summation, an unwritten epilogue to an epic and eccentric life story. That was why George Getschow, the cofounder of the influential Mayborn Literary Nonfiction Conference, decided there needed to be . . . something.

“If we didn’t do this,” he said, referring to the gathering he summoned on October 9 in McMurtry’s hometown of Archer City, “we would have missed an opportunity to celebrate Texas’s most influential writer. He’s shaped us, he’s defined us. The way we see each other is all through the prism of Larry’s eyes.”

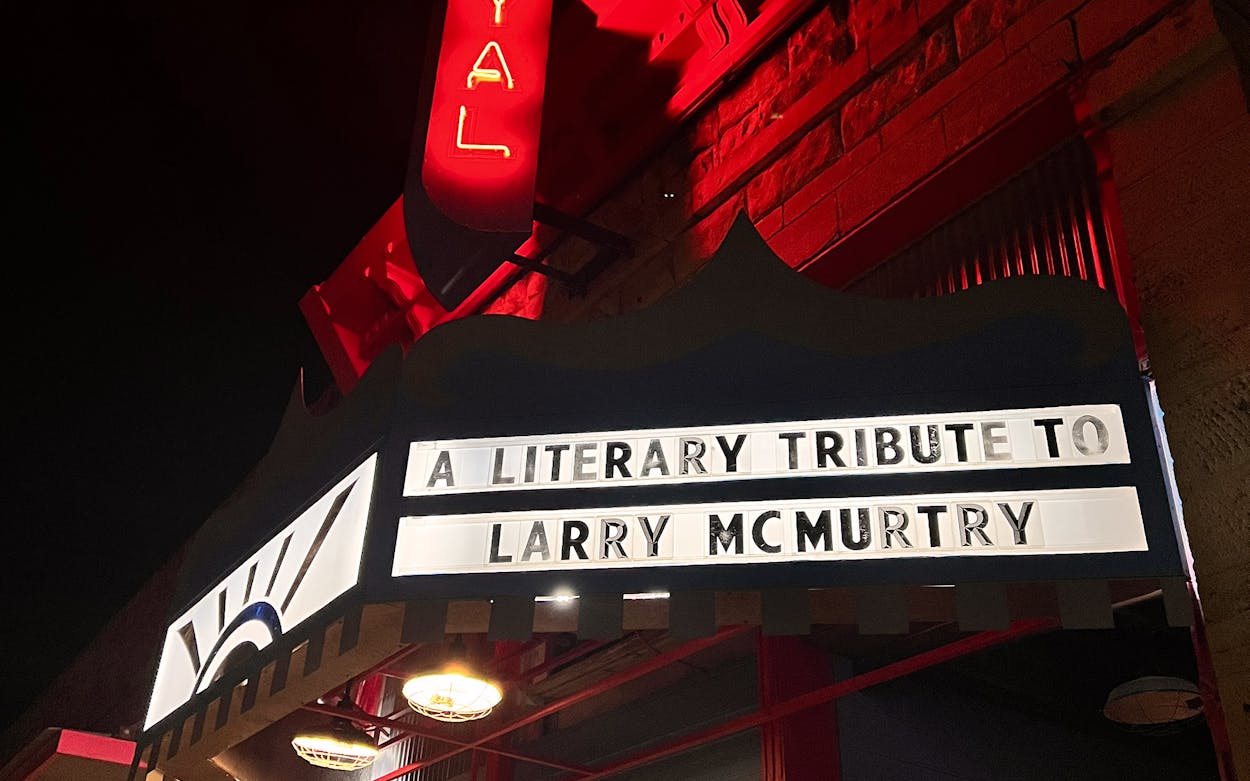

The title of the event, Larry McMurtry: Reflections on a Minor Regional Novelist, was a reference to the sweatshirt that McMurtry occasionally sported as a young Texas writer aware of, and ironically claiming, his outsider status with the distant New York literary establishment. A dozen or so writers, most of us from Texas, had been invited to contribute essays to a tribute volume about McMurtry that Getschow was editing, and to read from them at the Royal Theater, which had been not just the thematic focal point of Larry’s 1966 novel The Last Picture Show but an actual location where the 1971 film adaptation was shot.

The event was on a Saturday night. My wife, Sue Ellen, and I arrived in Archer City that morning, in time to hear about some minor literary carousing that had taken place the night before in the town’s only watering hole, the American Legion hall. We checked into Archer City’s only hotel, the twelve-room Spur, built in 1928 and lovingly refurbished with amenities that included floor-to-ceiling bookshelves in the lobby. The shelves were abundantly stocked with McMurtry titles, though some of us minor regional novelists, writers who owed our careers in part to the inspirational example or direct generosity of McMurtry, found some of our own books there as well. The Lonesome Dove suite, where Sue Ellen and I stayed, ran the length of the south end of the third floor, overlooking the intersection of Texas Highway 79 and Texas Highway 25 where, in the movie of The Last Picture Show, Sam Bottoms’s character Billy is run over and killed by a cattle truck. When we looked out the window, the view was as picturesquely desolate as it had been in the movie. Nothing had changed in fifty years except for the car models and the signs on the storefronts and the fact that this version of Archer City was in color and not in black and white. The traffic light suspended above the intersection still swung in a strong midmorning wind that we could hear keening around the sharp brick corners of the hotel.

“Larry’s influence on this town is immeasurable,” John Hudson, who owns the Spur with his wife Dotty, told me when I ran into him in the lobby. Hudson was born in Archer City in 1953, around the time The Last Picture Show is set, and had vivid memories of McMurtry’s rancher father—“always had his pants tucked in his boots and always had on spurs.” These days, he said, a third of his hotel’s guests are McMurtry fans, wandering around town in the howling wind taking photos of the buildings and streets where various indelible scenes were filmed.

That afternoon, we formed up a pilgrimage caravan of our own, made up of some of the writers who had come to Archer City to take part in that evening’s tribute. We walked the block and a half to Booked Up, one of the bookstores that McMurtry opened back in the eighties and nineties, hoping to turn this Texas plains crossroads of less than two thousand citizens between Windthorst and Seymour into one of the world’s great book browsing centers. There had once been four Booked Up locations in Archer City, housing some 450,000 volumes. But now there was only this one, and a sign on the door that day said the store was closed because of an unspecified emergency.

So we paid our respects elsewhere—beginning at the Dairy Queen, which Larry had immortalized as much as any Dairy Queen could be immortalized in a 1999 book of autobiographical reflections. A closer reader of that book, Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen, would have known to order a lime Dr Pepper, but I missed my chance at that salute when I bought a Dilly Bar instead. The pandemic was still settled upon the land, but the DQ was the only business in Archer City that seemed to have noticed, and as a result only the drive-through was open and our crew was not allowed inside to admire the faded McMurtry book covers that adorned the wall above one of the plastic booths.

There were four of us in my car on this self-guided McMurtry tour. Carol Flake Chapman, an Austin writer and poet and once the horse-racing correspondent for the New Yorker, had known Larry the best, at least during one part of her life. He had been her first boyfriend. When she met him at Rice in the sixties, he was already a celebrity, having published a first novel, Horseman, Pass By, that had been adapted into the Paul Newman movie Hud. His “reluctant, crooked smile,” she would recall at the tribute that evening, “and his seemingly limitless repertoire of quirky stories were irresistible.”

Sitting next to Carol in the back seat was Elizabeth Crook, who had met McMurtry only once, many years ago at a crowded book signing when he hadn’t bothered to look up to see her face as he joylessly wrote his name in her copy of one of his early books. But years later, unexpected, unhoped for, he gave her a cover blurb for her second novel, Promised Lands. It puzzled her, she wrote, “how someone so seemingly remote and indifferent to his nameless fans could be so generous to a beginning writer.”

Next to me in the passenger seat, keenly observing every scrap of non-scenery, was Geoff Dyer, the eclectic British essayist and critic whose celebrated, unclassifiable books on D. H. Lawrence, jazz, aircraft carriers, and oddball movies are all powered by an exultant curiosity. Last year, he had written an essay for the Times Literary Supplement about the wonder he had experienced when, several decades after the rest of the world, he had sat down to read Lonesome Dove. (“There was no book and no reader. There was just this world, this huge landscape and its magnificently peopled emptiness.”) When he heard about the tribute in Archer City, he wasted no time in booking a flight from his home in Los Angeles.

Across the highway from the Dairy Queen, in a residential area bordering the Archer City Country Club, is an old mansion that McMurtry bought in 1986 and used as his residence when he wasn’t living in Tucson, Arizona, or restlessly roaming the interstates. We gawked at it from the parking lot of the pro shop next door. With its multiple chimneys, terraces, and gleaming, green-tiled roof—not to mention the interior, which, according to a 2000 article in Architectural Digest, featured a canopied Balinese bed, a grand piano, and towering paintings of “lush nudes”—it seemed an improbable base of operations for a sometimes dyspeptic chronicler of barren places with a fondness for lime Dr Peppers.

Next, we drove sixteen miles out of town, down a dirt road toward a modest windswept promontory known as Idiot Ridge, to see the ranch house where McMurtry had spent his early childhood and later owned and filled with books. It wasn’t desolate, but it was a profoundly lonely place, and you could see at a glance how it might have brewed up in an imaginative child dreams of both escape and return. “I see that hill,” he wrote in Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen, “those few buildings, that spring, the highway to the east, trees to the south, the limitless plain to the north, whenever I sit down to describe a place. . . . I always leave from that hill, the hill of youth.”

For West Texans of a certain vintage, the same might be true of the Royal Theater—the embodiment of a small-town movie house with its beckoning marquee. Though the theater had been left in ruins by a fire a few years before the filming of The Last Picture Show, the old facade still had a starring part in the movie, and since then the theater had been rebuilt in an adjacent space as a performing arts venue.

That was where the tribute to Larry McMurtry was held that night. Beginning with three high school students from Midway Independent School District—“south of Henrietta, a little bit north of Jacksboro”—who had read Lonesome Dove in class and had staged a trail drive as a school project rather than having to write a paper about it—we all did our best to explain the imprint McMurtry had made upon us. Some of us had known him well. Others, like me, had known him a little, but enough to hope that in his mind our acquaintanceship had verged into friendship. Others had never met him but could trace their own journeys as writers back to a first reading of Horseman, Pass By or All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers.

But it was the outdoor screening of The Last Picture Show after the tribute that provided the most powerful testimony of McMurtry’s impact. It was projected onto the inner wall of what had been the original old Royal Theater and whose crumbling outer wall now looked like a Roman ruin. The movie was fifty years old, but to the several hundred people gathered in folding chairs to watch it as wind-driven dry leaves floated across the screen, all that vanished time had telescoped to nothing.

In the last few years, I’ve read with increasing interest the observations of people of color and other minorities testifying to the power of seeing themselves represented on a screen or in a book for the first time. It’s hard to remember now, but there was a time when even white Texans had not yet encountered a similar epiphany, having seen themselves represented only as caricatures or un-relatable and inflated heroes. What made Larry McMurtry count was the fact that he was unafraid to present an honestly observed Texas to Texans and the world. That’s why as we watched The Last Picture Show in Archer City it did not feel, even after half a century, that we were seeing a projection on a wall. It felt like we were looking in a mirror.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- Larry McMurtry

- Archer City