Institutions of long standing typically have figures the public associates with the place. At a magazine, that’s usually the writers, and at Texas Monthly, those names are well-known to longtime readers, who will occasionally write in and reference decades-old stories as if they ran just last month. They’ll recall Skip Hollandsworth on Dallas’s eyeball killer, Mimi Swartz on Channelview’s cheerleader murder plot, Gary Cartwright on Jack Ruby, Jan Reid on redneck rock, Prudence Mackintosh’s writing on her kids, or Pam Colloff’s reporting on the wrongfully convicted.

But inside Texas Monthly, in our own private folklore, there are figures who stand just as tall, if out of sight of the readership. They might have been the people who laid out the pages, enforced the comma rules, or made sure the magazine made it to mailboxes. They toiled long years without acclaim or big paychecks, but did so with a bright smile or ready song that made pressure-filled tasks like overnight deadlines bearable—even fun. These are the staffers who’ve made this place special and kept Texas Monthly going. Fact-checker Chester Rosson, who worked here from 1975 to 2006 and died this week after a long and absolutely unfair fight with cancer, was one of those figures.

At first blush, Chester was an odd duck. Short and mostly bald, save for a low-lying ribbon of thin white hair, he was built like a snowman, his face and torso almost perfectly round. A lifelong devotee of thrift store safaris, he was not afraid to wear shirts that looked pulled from a smaller man’s closet, always tucked snugly into a pair of dress slacks.

But once he spoke, once you heard his voice, that image fell away. He had a deep, rich baritone that dripped sweetness, and he knew how to use it. A trained vocalist and serious listener to all manner of music, he was often encountered mid-song. You’d find him rolling into the kitchen for a morning cup of coffee, singing a selection from Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado. Or sitting at his desk, rifling through a reporter’s files and humming one of Bach’s chorales. Or at a bleary-eyed, late-night editing battle at our stand-up desk, turning to a writer unwilling to accept one of his corrections and breaking into a favorite Roky Erickson tune, “You’re gonna miss me, baby.”

An Army brat born at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, Chester moved to his father’s hometown, Crockett, for junior high school, then studied German and biology at Rice University. In late 1975, he started at the magazine as a copy editor, part of the coterie of Rice University alums—founding editor Bill Broyles, his successor Greg Curtis, Griffin Smith, Paul Burka, and Anne Dingus—who powered the magazine in its early years and first brought it to national prominence. He left the magazine and Texas in 1979 with his wife, Barbara Burnham, who’d taken a job editing at Cornell University Press. But two years later they were back in Houston, where their son, Robin, was born, and a year after that, Chester was back at the magazine. He fact checked and edited, and wrote on topics that, as far as the edit staff was concerned, were squarely in only his wheelhouse, such as competing interpretations of Gustav Mahler by the Dallas and Houston symphonies and the peaceful resolution of a zoning dispute between San Antonio’s King William District and a 125-year-old German men’s singing club called the Beethoven Maennerchor.

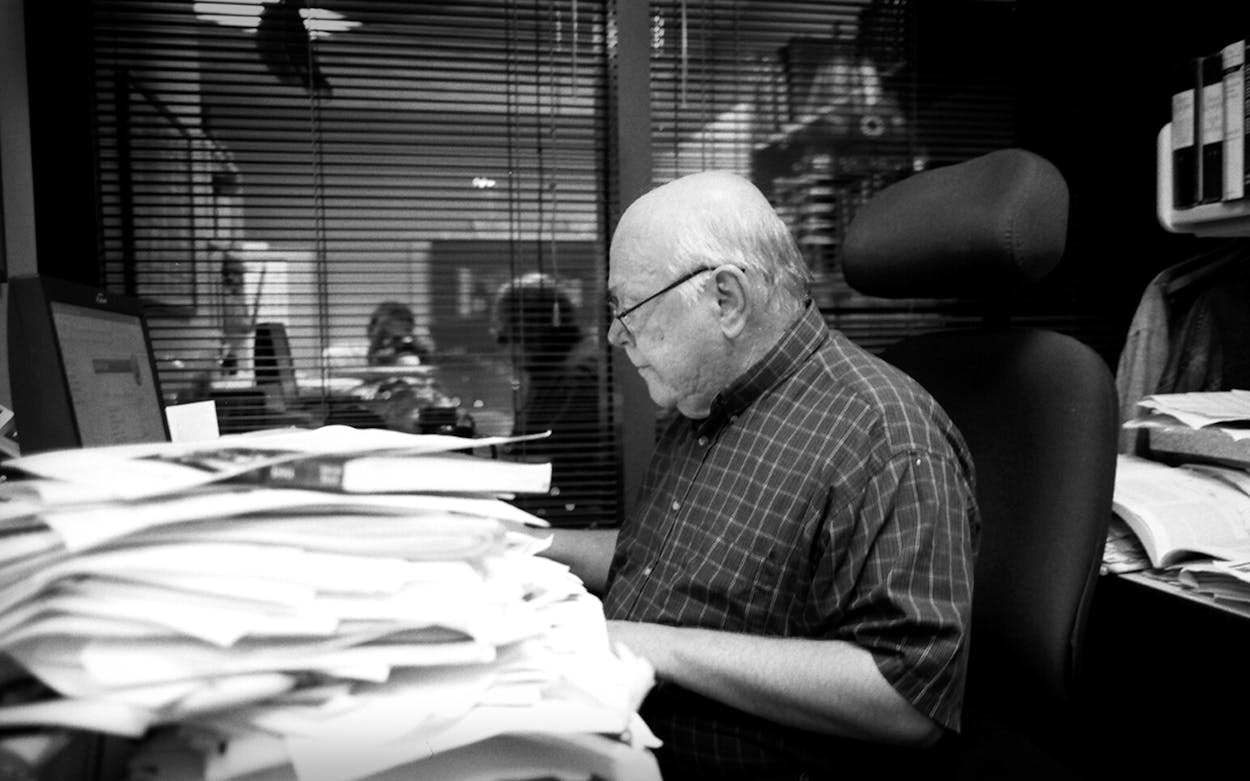

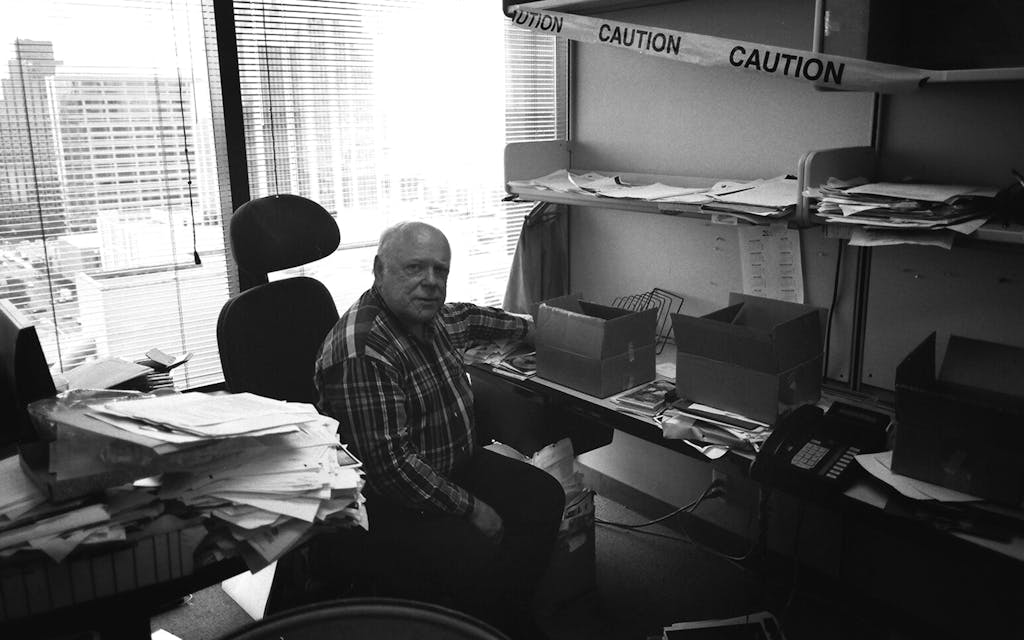

He moved to full-time fact checking in 1993, and that’s where I got to know him, after I hired on in August 1997. At that time, there were three of us in the fact department, and we were sequestered in a small space the size of a custodial closest, sitting in three cubicle carrels with a fourth space given to reference books and an old typewriter. Chester and David Moorman, Texas Monthly’s original full-time fact-checker, were already legends to the staff, essentially aesthetes and soul mates, but different as night and day. Chester was pure pack rat, his space overflowing with finds from monthly trips to the St. Vincent de Paul store—musical scores, old German-language magazines and books, photographs, record albums, little sculptures—all stacked to unreasonable heights and leaning at precarious angles. David, on the other hand, was a soft-spoken, erudite poet and minimalist, and his adjacent space was pristine. At any given moment, his two desktops would contain only his computer monitor, a short stack of the files he was working on that day, a copy of whatever he was reading at the time, and a tiny Zen rock garden the size of a candy dish. Once I established myself in the office—and became known for doing things like sneaking into Chester’s space when he was away and changing his screensaver to a photo of twelve-year-old country singer Billy Gilman—a copy editor started calling us Junk, Monk, and Punk.

But it didn’t take long to understand just how vital Chester was to the magazine. For one, there was his fact-checking, which I learned immediately is a thankless task. Every single date, name, place, quote, and event described in a story has to be checked with its source. When that source is a book, the job is easy. When it involves verifying a quote with the person who gave it—often someone who didn’t want a story written in the first place—the conversation can get ugly. From my adjacent cube, I heard Chester trapped in that kind of phone call all the time, but he never once responded with anything but grace. And later, once I made the move to staff writer, I relied on that grace when we worked on stories of mine.

Just as important were his extracurricular contributions. Loving to hear him talk, we started hosting semi-regular Chester Fests, at which he’d give wine-fueled, after-hours lectures to the edit staff on things like Glenn Gould’s versions of The Goldberg Variations and Debussy’s place in the Impressionist movement. He loved to bake cakes for colleagues’ birthdays, but only if there were a concept that merited his expertise: one was modeled to look like the Alamo, and it kind of did. But the best was a Dharma Bums–themed offering baked for David, a huge Kerouac reader, that had little figures carved out of marzipan running down the side of a big cake mountain. In those years, through dips in the economy and struggles by the company that purchased us from founder Mike Levy, none of us made much money, and the common refrain was that we played for the love of the game. But somewhere in there, I came to realize that we were actually playing for love of each other. Chester taught us that.

There’s one other Chester lesson that’s never far from my mind. One month, during another nasty deadline, Chester’s father died, just a couple days before the final close. Chester worked one of those days, then left the next to be with his people in Crockett. David and I covered his deadline obligations and finished up his stories, but I was writing a piece for the next issue and didn’t make it to the funeral the next week.

A few years later, my own dad died. And I remember riding to the service with my family in the back of the funeral home’s town car. As we neared the church, I looked out the window at my father’s friends, who were parking and heading to the sanctuary. On the last street corner, with a dozen or so crossing against the stoplight, I saw Chester, standing by himself, waiting patiently for the light to turn.

It remains one of my clearest memories of that day. I remember thinking that Chester didn’t know my dad, and that I’d missed his own father’s funeral. But rather than dwell on that regret, I decided to learn from it and pay the lesson forward. Chester was a gentle soul, a kind and gracious friend to everyone he met. And anytime we can be more like him, we are being better people.

The following are remembrances from colleagues over the years.

Michael R. Levy founded Texas Monthly in 1972, and he served as our publisher from the first issue in February 1973 until the close of the September 2008 issue.

The writers get the glory, but every one of them knows that without the fact-checkers and copy editors—without the Chester Rossons—truly great journalism is not possible.

Skip Hollandsworth has been a staff writer since 1989.

Chester loved classical music, and because I had a classical music background myself, we would invariably interrupt our fact checking sessions to sing snatches of great symphonic pieces to one another. I’d start out by belting Beethoven’s Fifth, of course, “Pom-pom-pom-POM!” Chuckling at my reliance upon an all-too-familiar tune, Chester would launch into Stravinsky’s brilliant and complicated The Rite of Spring. “Bom-dom-da-ta-ta-ta.” His voice sounded like a French horn—beautiful, resonant, the notes hanging in the air.

Then we’d get back to business, with a suddenly serious Chester asking me if I was certain the villain in my story had been stabbed eight times, not nine.

Pamela Colloff was a staff writer from 1997 to 2017. She is currently a staff writer working jointly for ProPublica and the New York Times Magazine.

Chester was very good at what he did—checking facts—for all of the obvious reasons: he was attentive to detail, well read, curious about the world, and loyal to the truth. But what made him stand apart was his bedside manner. His job often required him to ask difficult questions of strangers, yet he had a singular ability to put people at ease. More than once, when we were working on a tough story together, I would walk past his desk, eavesdropping on what I anticipated was likely a tense or awkward phone call between him and someone I’d interviewed. Invariably, I would find him chatting on the phone in his chipper way, or chortling appreciatively at something the person had just said, or just listening with the sort of careful attention that made the person on the other end of the line feel heard. He was able to find common ground with just about anyone, and he seemed as genuinely delighted by people—even eccentric, difficult, demanding people—as they were of him.

S.C. Gwynne joined the staff as a story editor in 2000, then was a staff writer from 2002 until 2008. He has since written four books, including most recently Hymns of the Republic (Scribner, 2019).

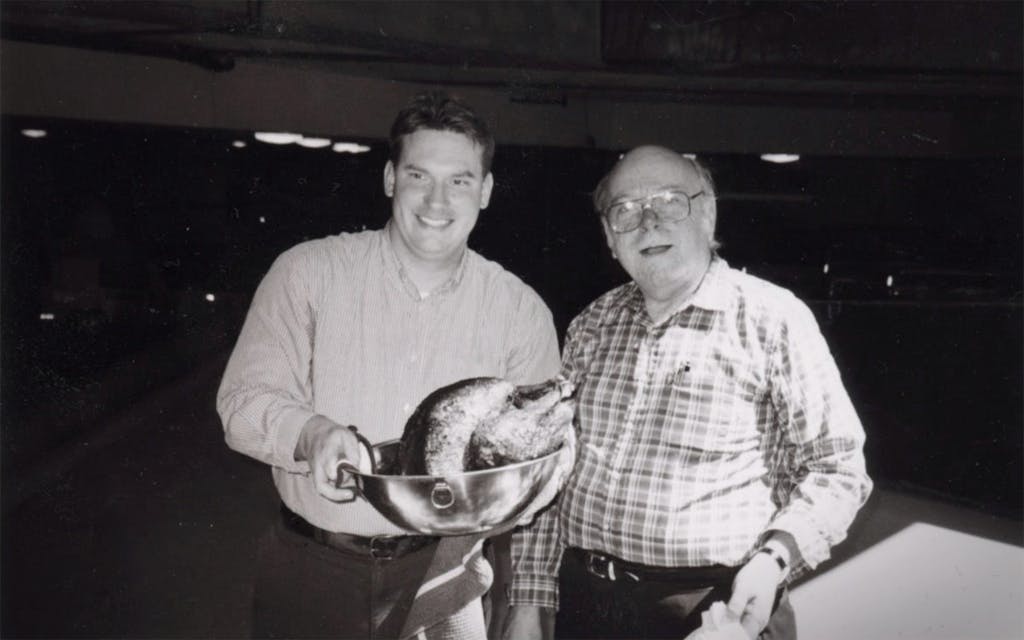

Chester was my introduction to the magazine. On my first day of work—this was in the days when the magazine occupied the top floor of Austin’s Omni hotel—I had parked my car in the garage and walked toward the elevator. But before I could get there, I encountered this odd little scene. Flanking the elevator vestibule was Chester Rosson, who was apparently doing nothing in particular . . . until I noticed the cylindrical aluminum apparatus at his feet, from which steam was rising. Chester was cooking something. In the parking garage. I had met him once before and knew who he was, and so I asked him, politely, what the f— on earth he was doing down there.

We then had the most lovely existential conversation. He said he was deep-frying a turkey. I said, “Well, Chester, I can see that, but why are you cooking a turkey in the garage?” “Because they wouldn’t let me do it in the kitchen,” he replied. Ah. And so on, until we got to the actual reason: he was trying out a recipe. I had just arrived from a thirteen-year career at Time, where the staff quite conspicuously did not try out recipes in the garage. And so we talked on, and I learned all about it.

What I remember about him then—and later when I got to know him—was just what a lovely, gentle person he was, and his explanation of TM’s weird habit of trying recipes before recommending them—the turkey experiment was for an upcoming Christmas feast feature—was just as civilized and smart as everything else he said. In the early days, when I was new to the culture, sometimes Chester would offer impromptu lectures on some piece of Texana. One day his subject was Domingo Samudio. Who? Sam the Sham. “Woolly Bully.” Who knew? Chester did.

David Dunham was hired to sell ads in 1979, and since then has served as publisher, associate publisher, and vice president of development.

A long, long, time ago I would host the annual Texas Monthly holiday party at our home. We always hired legendary Austin singer, pianist, and raconteur Margaret Wright to play and sing for us. She used to play all over town at places such as the Driskill and the Headliners Club, but we had a piano at the house, and we were fortunate to have that kind of smoky-voiced talent performing in her trademark, intimate cabaret style. Still, sometimes, after a few margaritas, some of us forgot to pay attention.

But not our friend Chester. Most years he would sit on the piano bench with her and sing along, with his killer baritone. He knew, of course, every word to every song. I had listened to Margaret for years at various watering holes, and I never saw her let anyone else sit on her bench. I think it was not only the quality of his voice, but the kindness that emanated from him.

Pat Sharpe has been a staff writer since 1974.

Chester was such a contradiction. He was roly-poly, bald, and short. His clothing was always rumpled, and he looked at times like he might hit you up for spare change. But he spoke like a cultured gentleman, and he sang like a nightingale. When the rest of us were bellowing “Happy Birthday” to some hapless coworker, Chester’s voice could be heard soaring over the crowd like an angel’s. His desk and office were disaster areas, yet he was a meticulous fact-checker. I don’t think he ever made a mistake, at least not on one of my stories. And he always had a twinkle in his eye. When he met you in the hall, he’d say, “Is everything wonderful!?”

Mimi Swartz became a staff writer in 1984, left to be a staff writer at the New Yorker in 1997, and has been back at Texas Monthly since 2001.

I knew Chester long before I came to Texas Monthly. He was a copy editor when I was a baby journalist at Houston City Magazine in the early eighties. I was always mystified by this guy from Crockett, who spoke like John Barrymore or maybe the head of any international opera company. He always seemed to know just a little bit more than I did about everything—history, German, classical music—but in a way that was welcoming instead of patronizing, and I loved him for that. When I landed at Texas Monthly in 1984, Chester made me feel welcome, especially with a laugh that could go from a deep baritone to a high-pitched giggle in no time, and that mischievous light in his pale blue eyes. As a fact-checker, he was brilliant—always thorough, but so diplomatic. Whenever he found a mistake in a story, he reminded me a little of an oncologist delivering both good and bad news: yes, there was an error, but we would recover with this fix or that. And we always did.

Stephen Harrigan has been a regular contributor to the magazine since 1973. His next book will be the novel, The Leopard Is Loose (Knopf, 2022).

Putting out a monthly magazine is a stressful enterprise. When there’s a difficult or sensitive story much of that stress falls on the fact-checkers whose job it is to contact a subject who, for one reason or another, might very much not want to be written about, or a source who might want to take back something he or she said in an unguarded moment. For that reason, in my experience, fact-checkers generally have the temperaments of diplomats. But it’s one thing to be unexcitable; it was another thing to be Chester Rosson. Chester lowered the temperature of any room he walked into or phone line he spoke on. Part of it was his voice—deep, melodious, with a chuckle-stress on every other syllable. Part of it was his undisguised appreciation of the spectrum of human weirdness. Much of it was simply his base-level kindness and pleasantness. He may have had his moments of anger, but if anybody on the Texas Monthly staff ever witnessed one, it has gone unrecorded. With an old-world courtliness and the appearance of a background figure in a 17th century Flemish barroom painting, he did not seem to belong to the era in which Texas Monthly began or the new era it managed—with his help—to survive into. He gave the impression of someone who floated free of time, who had just happened to pop into the twentieth century to take a look around and delight at everything he saw.

Katy Vine was hired to write and edit our Around the State listings in 1997, and she moved to staff writer in 2002.

In 1999, Chester fact-checked a story I had written about a reclusive cult musician in Houston who recorded under the name “Jandek.” To call this artist wary of coverage would be an understatement: Even during my interview with him, he would barely acknowledge he had any affiliation with the music, though he looked like the man photographed for the album covers, with a voice to match the singer. His music, which I guess some might call lo-fi blues or folk adjacent, struck me as unclassifiable or, at a minimum, unconventional. One hardcore fan, who hosted an unofficial Jandek website, described it to me as to me as “not just strange sounding but almost amateur sounding. His guitar is out of tune, and he can’t sing.”

Chester approached the excruciating fact-check call with the sensitivity and empathy I’d come to expect from him, and when he finished, he walked over to my desk and reported how it went. Apparently, as an opener, Chester told the artist that he’d detected the influence of Japanese Koto music in his work. No doubt, Chester’s respect for art and genuine interest in craft kept the call’s nervous recipient from hanging up. Chester could make anyone feel understood, and a reporter could learn from his patient listening. I certainly did.

Anne Dingus joined the staff as a copy editor in 1978, writing stories in that job, as a contributor, and as a staff writer until 2005.

Over the years I worked with Chester on scores of articles, maybe hundreds, from book reviews to the infamous Bum Steers. But I remember him more for his leisure activities. He was known for baking theme cakes, such as a D-Day cake for two colleagues who shared a June 6 birthday. He spoke fluent German. He loved to sing and always belonged to a choir; he regularly ushered for the Austin Symphony. And he often spent his lunch hour poking around thrift shops looking for hidden treasures. I still have a Virgin of Guadalupe medal he gave me.

I hope he’s singing to her now.

David Courtney joined the staff as a fact-checker in 2005 and debuted his column “The Texanist” in 2007. He became a staff writer in 2017.

Sometimes Chester would pick up an object he’d come across here or there, admire it for a moment, maybe offering a brief commentary on whatever it appeared to be. And then, on occasion, he’d bring it back to the office with him, where he’d place it on one of the cluttered bookshelves in his cubicle. He referred to such items as his “treasures.”

I recall one such “treasure” he added to his shelf after walking back from lunch downtown. “What do you have there, Chester?” I asked. “I don’t know,” he replied, studying the object, which resembled a small red railroad spike. “I think it’s the heel to a woman’s shoe. I found it in the crosswalk on Sixth Street. I can’t imagine what might have become of its owner.”

Evan Smith joined the staff as a senior editor in 1992, was deputy editor from 1993 to 2000, then served as editor until 2008, when he became president and editor in chief. He cofounded the Texas Tribune in September 2009.

Chester had enthusiasms for certain fruits, particularly Texas fruits. One day I encountered him in the kitchen eating a peach. I’m going to say it was from Fredericksburg. I mumbled something to him to the effect of, “Hey, nice peach you got there, Chester,” and he frowned and sighed. “Yes, but it’s not the peach of my dreams.” That was funny.

But what I remember most—other than his unfailing kindness, his genuine curiosity, his love of Texas, and especially his love of Texas Monthly—was his clutter. The Duggars had nothing on this guy. There were piles of papers, dusty books, and random cultural artifacts everywhere in his cubicle. Total fire hazard. He barely had a way in or out. But he had a system. He knew where everything was. At a moment’s notice he could find anything. I suppose that’s what made him a great fact-checker—one of the best backstops any of us had the good fortune and high honor of working with over decades.

William Broyles was the magazine’s founding editor, serving until 1981. He subsequently went on to a career as an acclaimed screenwriter, receiving an Oscar nomination in 1996 for Apollo 13.

Chester was a true lover of English, and that love affair lasted his whole life. He was not fussy or pedantic, just endlessly curious about our language, and he never tired of exploring its nooks and crannies. He was dedicated to making sure Texas Monthly spoke with a sturdy, precise, clear, and consistent style. His joy in the simple things and his very specific, subtle, and ironic sense of humor made him one of the most enjoyable people I’ve ever worked with. It was touch and go there for a few years at the beginning, and Chester was a key part of the Rice University contingent that helped set Texas Monthly on its feet and kept it going for so long. I will miss that sly smile and that gentle spirit. It lives in every page, over all those many years.

Gregory Curtis was on the magazine’s original editorial staff and served as editor from 1981 until 2000. He has since written three books, including most recently Paris Without Her: A Memoir (Penguin Random House, 2021).

One day in the mid-afternoon I was in the room where the fact-checkers worked. I heard Chester on the phone talking to Barbara and in the quietest, most longing tone he asked her, “What are we having for dinner?” I just had this vision of Chester as this very satisfied burgermeister who lived for serene evenings at home. He loved to laugh, but he was also unflappable. He might fret a little, but otherwise pressure never affected him.

Brian Sweany joined the staff as a copy editor in 1996, became a story editor in 1998, deputy editor in 2007, and served as editor in chief from 2014 until 2017.

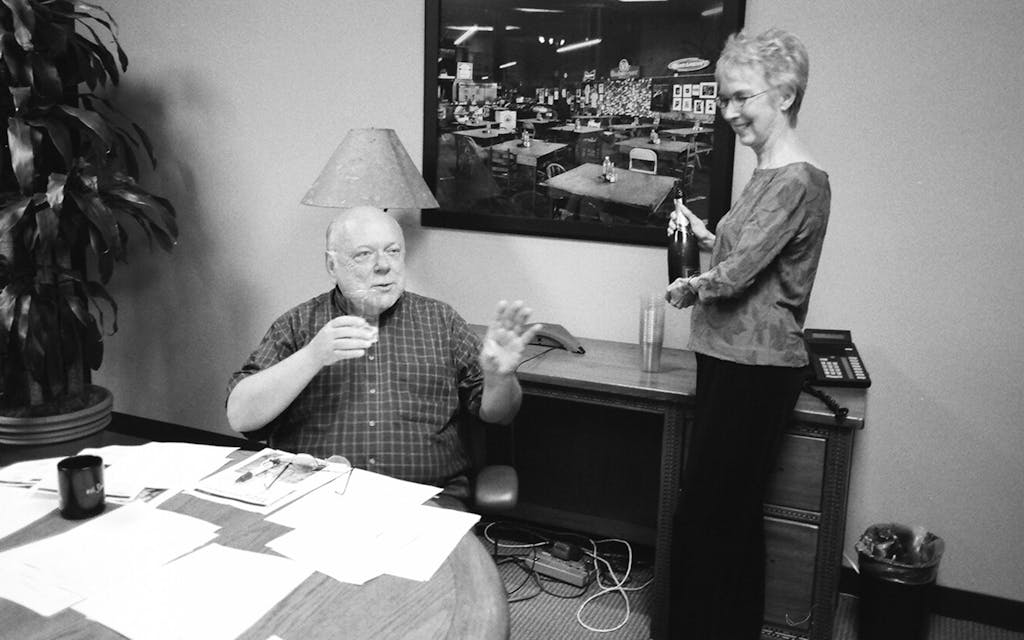

For many years I was fortunate to start each morning the same way: Shortly after nine o’clock, Chester would appear in my office, coffee mug in hand, and ask in that distinctive voice of his—mellifluous and friendly, with the vowels stretched just so—”Is everything wonderful yet?” Then he’d sit and visit for ten minutes or so. Sure, we talked about the magazine and deadline and stories we were working on, but we talked more about Barbara and Robin, or his love of cooking and baking. He’d recommend composers I’d never heard of and books I’d never read. He was the first person to tell me I should try out this newfangled search engine called “Google.” And if you wanted to know anything and everything about Wagner’s “Ring” cycle, Chester was your man.

We grew extremely close. The first travel I ever did for the magazine was with him. Our managing editor, Jane Dure, asked me to drive Chester to Houston to fact-check a story on the Montrose neighborhood. We were an odd couple for sure—our age, our personalities, his complete fearlessness in the face of anything new—so he particularly loved to tell the story of the two of us hanging out in a gay bookstore, chasing down an errant fact in the copy. On another trip, we drove to the childhood home of Katherine Anne Porter, in Kyle, where he told me more about her life and work than I had ever learned as an English major.

I suppose the day I remember most seems typical of what times were like at Texas Monthly early in my career. Sometime in the late nineties (Chester could have confirmed the exact year in minutes), Jane asked us to fact-check a recipe for deep-frying a turkey. That project seemed very straightforward and right up our alley, except for the fact that the two of us set up shop—with our giant fry-pot, gallons of peanut oil, a propane tank, and an appropriately sized turkey—just inside the entrance to the underground parking garage of our downtown office building. I have no idea why we did that, as cars would pull in and drivers would wave at us tentatively. Either one of us should have known better, but the pursuit of quality magazine journalism knows no sense of safety or danger.

The picture from that day is one of my favorites from my years at Texas Monthly. Needless to say, building management found out and trouble ensued—though the turkey was delicious. The morning after our adventure, Chester appeared, coffee mug in hand, and said with a laugh, “Is everything wonderful yet?” Yes, Chester, it absolutely is.

Andrea Valdez joined the staff as a fact checker in 2006, then served as editor of our website from 2013 until 2017. She is currently a managing editor at the Atlantic.

When I started as a fact-checker in 2006, it was ostensibly to fill the position Chester was leaving. But there was no replacing him, certainly not by me. And though our professional overlap was minimal, his long presence at the magazine cast a bright, lasting afterglow; the phone calls from his friends that kept coming for months on the office line I inherited were just one of many reminders.

But I got to know him a little in the weeks before he left, while I was learning the fact-checker’s trade and he was struggling mightily to clean out his space—with a heavy assist from David Moorman. It was a great window into the loving dynamic between them. Which is to say, the idiom “opposites attract” has never been more on display to me. When they finally finished, David went to work on what he called a “Chestafarian Shrine”: a dollhouse-size diorama made up of toys and trinkets swiped off of colleagues’ desks, along with select items of Chester’s detritus, things like business cards he’d collected from the streets of downtown.

He presented the shrine to Chester at his retirement party, a large gathering at the Driskill bar. Chester invited me and sweetly insisted I go, and I remember feeling so very out of place as a young, scared nitwit who knew nothing and no one. But Chester stood close by and made sure to introduce me to everyone . . . and everyone to me. There was no replacing the irreplaceable, but it felt good to have his endorsement to join the family.

David Moorman was a fact-checker from 1975 until 1984, and then again from 1987 until 2016.

Chester Rosson. Patient. Genial. Kindhearted. Mild mannered. Slow to anger. Quick to recover his composure. Good company in all seasons. The last time I saw him was four days before he died. He was anemic and tired even by late morning yet compensating gracefully in such a way as to be delicately poised. He seemed optimistic about enrolling in an emerging immunotherapy trial, for which Dr. James Allison at MD Anderson won a Nobel Prize in 2018. I mentioned some news articles about the Johns Hopkins psilocybin project, and I asked Chester how he felt about this as a possible palliative therapy. He immediately explained that on more than one occasion he had experienced the wonderful ecstasy of Shiva and Shakti dancing together, and so he felt no need to go further at this time.

Michael Hall joined the staff as a story editor in 1997 and has been a staff writer since 1999.

Chester was so calm and cheerful, and sometimes, on deadline, he’d be the only calm and cheerful person in the entire office. He was always so gentle, whimsical, and super sweet. Everybody adored him. When Greg Curtis retired as editor in 2000, he had one final editorial meeting to lead. Sitting at the head of the conference table, Greg began saying a sentence or two about each staffer. Most of it was specific, insightful, encouraging, and very much appreciated—we were ambitious journalists, wanting to make a mark on the world. He said things like, “You’ve always had so much potential—and you really grew into it on Story X. I cannot wait to read more.” And: “You really found your voice on Story Y. The magazine has always needed stories like that.”

He finally got to Chester. And Chester had written many things over the years—usually short pieces about symphonies and operas—but he wasn’t eaten up by ambition like a lot of us. Chester was . . . Chester. So when Greg got to him, he just said, “Chester, we all love you.” Some of us had tears in our eyes and others just smiled. It was the truest thing Greg said all day.

Suzanne Winckler was hired as a proofreader in 1974 and was the architect who designed and built the magazine’s copy and fact departments. She switched to story editing in 1978, serving until 1984.

I like to say I hired Chester to work at Texas Monthly. So you can thank me because he enriched your life as well as mine. Of course, others approved this decision, Bill Broyles, managing editor Anne Barnstone, Pat Sharpe, no doubt others.

We were trying to establish in those early days a little team of keepers to mind the language and the typos, which back then were rampant. The writers and reporters were mostly wonderful and brilliant. They just needed dusting and polishing and corralling. They did not always appreciate us but onward we went. We were establishing order and truth!

I left Texas Monthly in 1984. One of the hardest jobs I have is trying to stay in touch with far-flung friends. It was a challenge to keep track of Chester—he was something of a recluse—but I badgered him, and we managed to see each other from time to time. He and Barbara and little Robin came to visit our farm in northern Minnesota. My husband, David, took Robin on his first—perhaps his last—tractor ride. Chester came to visit us in Mesa, Arizona, where we sat in the backyard watching our flock of chickens, a favorite cocktail-hour pastime.

Chester was kind, gentle, easily bruised by unkindness. He had a streak of melancholy—something I recognized and shared with him. Laughter, as those of us with a tendency to sadness know, is the best path out of despair, and Chester had a wonderful laugh. I can hear it now.

Thank goodness David and I got to laugh with him in April 2021. With the first glimmer of freedom from COVID, we flew to Texas to go birding on the upper Texas coast. I called Chester. He had just gotten out of the hospital from his first surgery related to his cancer. We drove to his house in Crockett. We wore our masks. We had a spot of wine. We laughed like crazy. His house is a museum of artifacts, books, art, knickknacks. He showed us the photo of him dressed like a little cowboy on a pony—the classic Texas photo of kids in the 1940s and 1950s. (I have my own pony photo taken probably on a visit to see my grandfather in San Antonio.)

As we were leaving Chester rushed out to cut some flowers in his yard. He put them in a little vase and gave them to us. I will remember that simple gesture; it was so very Chester. I will remember, too, him laughing.