On May 30, 2016, The Jerusalem Report ran a cover story titled “SpaceIL: To the Moon.” It told an improbable story about a trio of young Israelis – Yariv Bash, Kfir Damari and Yonatan Weintraub – who at the last minute entered a Google contest to build a moon lander.

That’s not a typo. A moon lander. Big outlandish dreams! NASA’s 10 moon landers cost $21 billion to develop and build.

On April 12, 2019, against all the odds (and I mean, really against all the odds) the little Israeli lunar lander came within a few yards of safely touching down on the moon’s surface before crashing.

Thomas Edison once said failure is a steppingstone to success. He’s right. If all goes well, a new Israeli spacecraft, version 2.0, will land on the moon in 2024.

This is the inside story of Israel’s moon lander, based in part on an Israel Story podcast by Judah Kaufman, aided by Joel Shupack and Adina Karpuj (https://www.israelstory.org/episode/diy/).

Prologue: We came so close!

April 12, 2019. Bash, Damari and Weintraub huddle in a control room at the headquarters of IAI (Israel Aerospace Industries), along with then-prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu. It is nearly midnight. The Israeli lunar lander, named Beresheet (Genesis), is readied for its final descent onto the moon’s surface.

The Israeli team had worked for over a decade to build the little spacecraft. It had traveled 384,000 kilometers (230,000 miles) through space, to orbit the moon. It is now descending and braking. It looks good!

Then, the main engine doing the braking fails. The lander is descending too fast. The operators succeed in turning on the main engine again – but it is too late. Beresheet is silent. In the control room, the altitude reading freezes at 149 meters (about 500 feet, or a tenth of a mile).

Beresheet had just crashed and exploded onto the surface of the moon. It came agonizingly close to a soft landing.

The little spacecraft sent back a final ‘selfie.’ With the moon as a backdrop, the photo shows Israel’s blue-and-white flag engraved with these words: In Hebrew, Am Yisrael Chai (the Jewish people lives!) and in English: “Small country, big dreams.”

Act one: Cockeyed optimists

In Rodgers and Hammerstein’s hit Broadway musical South Pacific, Mary Martin sings: “When the sky is a bright canary yellow, I forget every cloud I’ve ever seen, So they call me a cockeyed optimist, immature and incurably green... I’m stuck like a dope with a thing called hope.”

You want to talk optimism? Tempered with chutzpah, genius and stubborn persistence, plus high-level scientific and engineering skills?

In September 2007, Google announces a challenge: the Lunar XPrize, offering $20 million to the first privately funded team that lands an unmanned rover on the moon, travels 500 meters (1,650 feet) on the moon’s surface and sends photos and videos back to Earth.

Thirty-one well-financed teams sign up, including those from the US, China, Russia, India and Spain. Some foreign teams had been working for three years on their proposal.

Kfir Damari reads Yariv Bash’s Facebook post: “Who wants to go to the moon?” Kfir responds, “If you’re serious, I’m in.” The duo adds Yonatan Weintraub to the team.

Their skills are well-balanced: Yonatan is a space engineer, interning with IAI. Kfir is a communication systems engineer. Yariv is an electronic engineer. They scribble rocket science equations. They pull out graph paper and draw up a plan.

Approximately 400,000 people worked to get an American astronaut to the moon. The total cost of the first six lunar missions, in 2020 dollars? About $200 billion. That is half of Israel’s annual Gross Domestic Product.

The cockeyed optimist team has to scrape together the Google XPrize entry fee of $50,000, long before crowdfunding became possible.

After hard work, they have $30,000 in their newly opened account, opened a week earlier. Friday morning, December 31. They check their balance: $52,000! They wire transfer $50,000 to Google. Their application is accepted.

The group assembles a team of nerds to build a rocket ship. And they design a Coke-bottle-sized lunar lander. Why? It has to be small because it takes a lot of fuel to get to the moon.

Act Two: Morris Kahn, investor hero

Morris Kahn emigrated to Israel from South Africa. He built a highly profitable company, Israeli Yellow Pages, then pivoted it to become Amdocs, in 1982, perhaps one of the last Israeli start-ups (now employing 25,000) to avoid acquisition and remain independent. Amdocs pioneered billing software for cellphone companies and remains a market leader.

The optimistic trio, Kfir, Yariv and Yonatan, had to raise $100 million. Impossible? How in the world do you pitch to an investor the value of a moon lander?

The answer: education. Show Israeli kids that science is exciting, that they can do amazing things with it.

This, indeed, was the goal of American’s moonshot, as announced by President Kennedy at Rice University in September 1962: “We will go to the moon!” And it worked. A whole generation of young Americans studied engineering and science, inspired by the Mercury program.

“We want to promote STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) education in Israeli schools,” Damari told The Report in 2016. “We are building the first Israeli moon shot. The kids, they will build the next one!”

Morris Kahn used his personal wealth to provide a substantial chunk of the $95 million budget, along with other philanthropists and later, the Israel Space Agency. Kahn continues to support the lunar lander project, as we will learn later.

Act Three: Build a rocket. Really?

Nearly every start-up needs to build a prototype. So did SpaceIL. They had to find a way to shoot the lunar lander high into the air and see if it could land intact. To do this, they had to build a missile. And – to get permission from IDF. In Israel, missiles can start wars.

A group of engineering students makes the rocket engines. One of them mixes the highly flammable fuel in his bathtub (yikes!). They assemble the pieces of the ‘moonshine’ rocket on launch day. And very late one night in 2011, they set off for the launch site in Beit She’an Valley.

Expectedly, they run into a hitch. One of the batteries is missing. Without it, no launch. Finally, at the last gas station before reaching the test site, they find the right battery. Phew.

At 6 a.m., all is ready. Countdown. Blast off. Everything works perfectly. The little lander soars into the sky and then lands intact. “Lo nachon!” (Unreal!), says Damari.

Act Four: Dogged persistence

The year 2014 came and went. That was the deadline Google set for the Lunar XPrize. None of the teams met the deadline, and Google pushed the deadline to 2017, then to March 2018.

Most of the teams dropped out. Not SpaceIL. They hired a CEO, raised tens of millions of dollars, and became a seriously focused operation. Yonatan left for Stanford in 2014, but Kfir and Yariv stayed on, joined by hundreds of volunteers.

Kfir and Yariv kept their promise. They spoke to kids in schools from the top of Israel, in Metulla, to the bottom, in Eilat. Kfir recalls how one kid asked for his autograph – as if he were a soccer or basketball hero.

On January 23, 2018, Google announced that the $20 million prize would go unclaimed. Xprize became ex-prize.

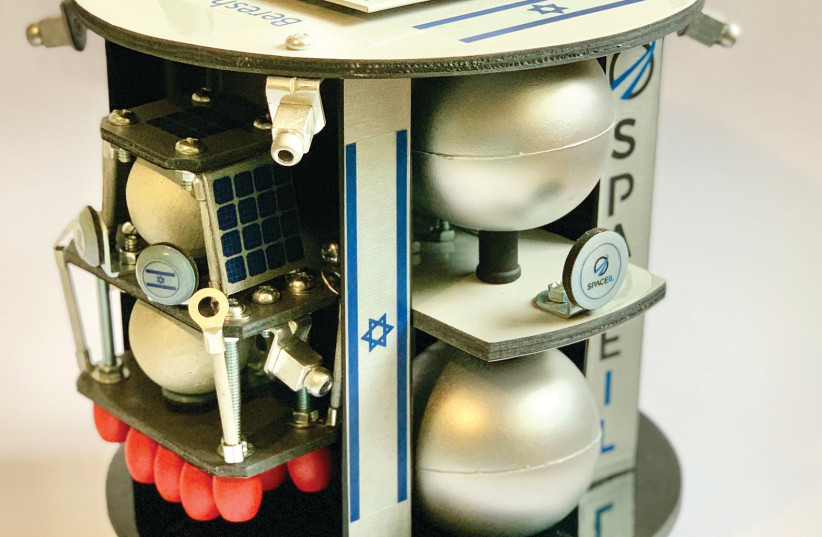

SpaceIL soldiered on regardless. Beresheet was completed and prepared for launch. It weighed 150 kilograms (330 pounds), stood 4’11” tall and was similar in width to a washing machine. Beresheet used seven ground stations on Earth for communications.

As noted earlier, it crashed just before landing on the Moon. The cause: The lander’s gyroscopes, devices used to maintain direction and orientation, failed. This caused the main (braking) engine to shut off. The crashed lander now rests forever on the Moon.

There was a booby prize. Google awarded SpaceIL $1 million to support the second mission. I think Google might have been more generous – the market value today of Google stock (known as Alphabet) is $1.9 trillion.

Act Five: Not one but two!

It was reported in July that SpaceIL had managed to raise $70 million toward the $100 million cost of Beresheet 2. Again Kahn invested, along with French-Israeli billionaire Patrick Drahi, and others.

Writing in ISRAEL21c, Abigail Klein Lachman reported that in 2024, the plan is to launch not one but two ultralight lunar landers – one to land on each side of the moon – plus an orbiter that will circle the Moon for several years and will conduct scientific experiments with the help of students from around the world.

Kahn, chairman of SpaceIL’s board of directors, said that he will do everything in his power “to take Israel back to the moon, this time for a historic double landing.”

Epilogue: The little spacecraft

The SpaceIL team published a 26-page children’s book, The Little Spacecraft, written by “Dr. Mom” and illustrated by Shana Koppel. It features Berrie, a little spacecraft with a big dream. She wants to go to the Moon! But how will she prove to everyone else that small can be powerful, too?

Here is the book’s first page – a fitting epilogue to our story:

Dedicated to the little dreamers. The girls and boys who dare, who try, who fail and try again. To the ones who aspire to reach new places far beyond the horizon. And to their parents who instill in them the confidence to know that no matter if they proceed or fail, they will always have a safe place to land.

The writer heads the Zvi Griliches Research Data Center at S. Neaman Institute, Technion, and blogs at www.timnovate.wordpress.com