Tales from the hardwood: What it was like to play SEC, Southwest hoops in the '60s

At the beginning of my less-than-storied college basketball career in the early 1960s at Rice University in Houston, there were the old Baylor Bears, who played basketball in a dusty rodeo grounds, the Heart of Texas Coliseum.

There was Texas Tech, also in the old Southwest Conference, with its rowdy, boot-stomping West Texas fans playing in Lubbock Municipal Coliseum. The University of Texas played in the 4,000-seat Gregory Gymnasium, built-in 1930.

Moving closer to home in the Southeast Conference, Auburn — recently the No. 1 rated team in the nation — played basketball in the 2,500 seat Auburn Sports Arena — Charles Barkley came much later.

LSU also played in an old agricultural and state fair facility. As did Pete Maravich. The Florida Gators had less chopping power. Tennessee went 4-19 in 1962.

There was no three-point shot. College basketball had two referees. There was only one John Wooden, who grew up, by the way, milking cows with no electricity on a farm near greater Hall, Indiana.

His top salary as UCLA won 10 NCAA championships through the mid-1960s to '70s was $32,500.

And there was the no-dunk rule instigated for 10 years in the late 1960s and attributed to one of those UCLA Bruins — Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Now kids are dunking in middle school.

So what’s changed in those 60 years?

For openers, so many of those then mediocre, unknown teams we played have now moved way on up. Baylor was 2021 national champion, taking down mighty Gonzaga.

Texas Tech was 2019 runner-up to Virginia in overtime in 2019. Texas has been ranked much of the year.

Where have you gone, Indiana and Louisville?

On a more personal level, today's teams are bigger, faster, stronger, more athletic, better coached, better housed, traveled, nursed, fed and appreciated. I am not sure I could even get a shot off in today’s game — much less make one.

Naismith's original 13 rules of basketball

Basketball has been constantly subject to change since 1891 when Dr. James Naismith hastily wrote the first 13 rules of the game at a YMCA in Springfield Massachusetts and a janitor found him a peach basket.

![The 13 original rules of basketball annotated by Dr. James Naismith, the sport's inventor, are on display at The Avron B. Fogelman Sports History Museum at FAU. The rules were produced for Naismith's 1934 manuscript, including his hand-written notations. They include three typewritten pages mirroring what Naismith had created for college students when he invented the game in 1891 [ALLEN EYESTONE/palmbeachpost.com]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/xa7O0T13tKwETGXfP_4qbw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTEwODM-/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the-courier-journal/c578c6d110307608aaa81b029659c44d)

His original “basket ball” rules, quickly scratched out in desperation to give bored athletes something to do between football and baseball, allowed batting a ball in any direction with one or both hands — but never the fist.

No dribbling allowed. Any ball that went out of bounds could be tossed back in by the first person then touching it; mayhem in aisle six. No shouldering, holding, pushing, striking, or tripping is allowed. Sure, Doc, no problem.

Naismith also suggested the game have two halves — originally 15 minutes each. Women’s college basketball became four 10-minute quarters.

Take your pick. Given all the commercials, referee timeout checks and half-time blather, both genders really need a two-hour time limit for a 40-minute game.

Playing basketball at a bunch of football schools

In 1961 the Southwest and SEC conferences teams we played — Baylor, Texas Tech, Texas, Arkansas, TCU, Tennessee, LSU, Florida and Florida State — were mostly football schools. Not one of them lasted in the NCAA top 25 basketball teams that year.

Not counting, of course, Kentucky and a guy named Rupp.

The main big reason for the upgrade is those Southwest and SEC conference teams — including Rice — were not integrated. Nor were their student bodies to any real extent.

The general lack of basketball interest was so bad that TV stations in Houston did not even broadcast the NCAA finals in the early 1960s.

That all changed for the significantly better when the underdog, all-Black Texas Western team beat an all-white and top-rated Kentucky in the 1966 finals. Our Rice freshman team played against the leading scorer in that game, Texas Western’s Bobby Joe Hill, while he was at Wharton Junior College in Houston.

A subsequent movie on that NCAA win, Glory Road, exposed the racism and discrimination of the day — with Jon Voight as Adolph Rupp.

Then the University of Houston added Elvin Hayes and Don Chaney and got to the NCAA finals in 1967 and 1968, winning a 1968 regular-season nationally televised game against mighty UCLA that drew a record 52,693 fans into the Astrodome.

UCLA later destroyed Houston in 101-69 in NCAA finals. This year’s Houston team is ranked top five in the country.

The women’s game, aided by the much-needed passage of Title IX in 1972, then started on its long and still unfulfilled path to equality. New rules now allow college players to be paid — long overdue — but with the inevitable results: the teams with the richest alumni and post-graduate connections will soon win the most games.

High school ball in a small Illinois town

It’s good, fun and educational to look back on what was college basketball like 60 years ago — its improvements and problems. I’d played my high school ball in Sycamore, Illinois, in a glorified Quonset hut that held about 800 people and provided sheet-metal showers in its dim, crowded concrete basement.

We were in a small-town, integrated conference set mostly along the Fox River outside Chicago. My senior year we somehow had about eight Division 1 players. I didn’t win a jump ball all year.

One opponent’s gym was so small a guy driving for a layup stumbled and fell through an outside door behind the basket into a snowdrift. Another conference town, Batavia, produced a guy named Dan Issel who matriculated at the University of Kentucky with some success.

A kid from nearby Geneva, Hack Tison, played for Duke in a Final Four.

In high school, we traveled to games through endless cornfields in a big yellow school bus. Mostly heated. So getting on an airplane to fly to a basketball game was a memorable experience.

Actually, as any old athlete can tell you, the final scores of past games are much less remembered than your teammates, the getting there, what happened along the way, and the memories that linger afterward.

I did once score 20 points in a college game but can’t remember who we played. Nor will they.

Sweating it out in Houston

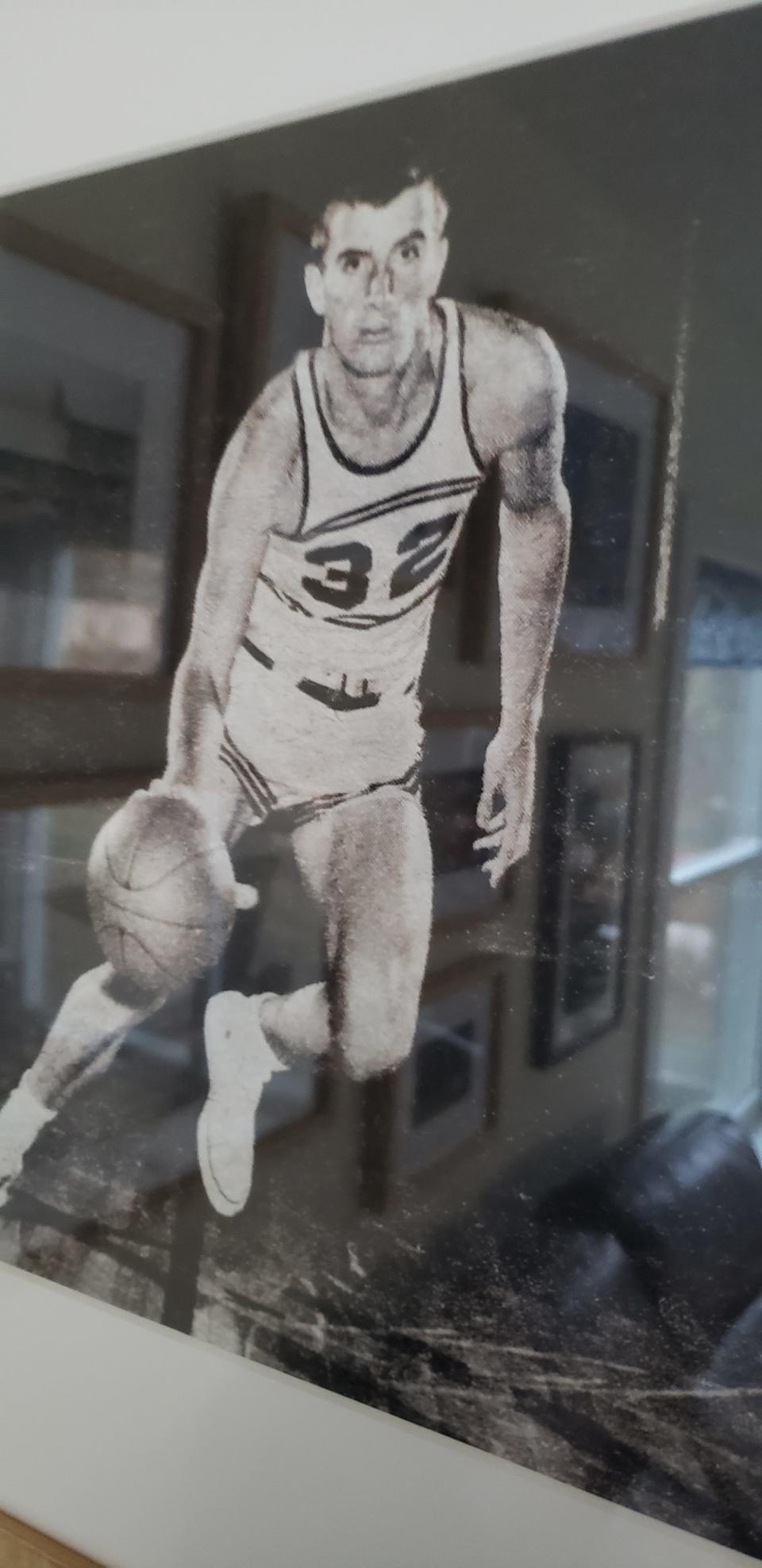

In September 1960, I was 17, a very lean 6-foot-4 and headed 1,065 miles south to a great adventure in Texas. In basketball litany, I was a damn good shot, an adequate passer and rebounder and had little interest in defense.

Our coach held the same beliefs.

Rice was “one of them academic schools” as U of L legend Milt Wagner so finely expressed years ago. It was a university of 1,600 students with a 70,000-seat football stadium — which it filled for many games. This was Texas.

We practiced and played basketball in 5,200-seat Autry Court that had no air conditioning in hot and humid Houston, but at least our gym roof never leaked in a rainstorm, delaying a game.

We had a decent team, my roommate, Kendall Rhine, eventually playing for the first Kentucky Colonels in Louisville.

Our college basketball locker room was in the far corner of the football facility, a square box with pegs on the wall for our pants, a far cry from today’s mega-million locker rooms. It also had sheet metal showers.

Freshmen were not eligible, which may have been a good thing because our coach was a part-time insurance salesman prone to blowing cigar smoke in our face.

We had only one varsity coach hired from a local junior college and given an occasional assistant. He was followed by a high school coach with no college experience.

You look at a college basketball bench now and there are a dozen eager-looking assistants lined up like a Christmas choir. We had grainy game films, no scouting reports, analytics, statistics or the incessant mention of “KenPom” ratings.

And well-written game stories were expected in the newspaper the next morning.

When your jersey number can't be higher than 5

Auburn ran an offense called the “Auburn Shuffle” requiring three, four, or five Auburn players to shuffle over to another place on the floor recently relinquished by a teammate who had just shuffled off to somewhere else. Now Auburn runs up 80.6 points a game.

My true journey began at the University of Florida; an airplane trip, my first college road game; a big moment for a cornfield kid. The NCAA had apparently just figured out referees only had five fingers on each hand — thus making it difficult to call fouls on any player with a jersey number larger than five. Using two hands was a bit clumsy; it took both to rack up a number seven.

No one had told the Rice basketball uniform supplier — or apparently the athletic department — of a new rule prohibiting jersey numbers above five. All Rice Owls who entered the game with such would be given technical fouls.

Clearly, some uniform alterations were required in our locker room. Some of the higher numbers were just ripped off. Other guys had new numbers literally taped on. A few jerseys were just switched. We were an NCAA Division 1 basketball team gone seamstress.

Because I was the eighth or ninth man on the team, I ended up wearing, like 67, which prevented me from ever entering the game without getting a technical foul. And I didn’t.

First game in my career. Glory road.

We played LSU in something called the John M. Parker Agricultural Coliseum, which, as the name implies, was an agricultural coliseum. As in livestock and such.

That also implied some random dirt and grit in the facility, which did require we run out from our locker room to the basketball floor on a raised wooden path laid on agricultural dirt — or maybe worse?

Pete Maravich was a couple of years after us — I regret missing him. LSU now plays in the Pete Maravich Assembly Center. I met him once later at a book signing. Nice guy.

Moving along in the 1960s SEC, we played the Tennessee Vols in the clunkily named University of Tennessee Armory-Fieldhouse. It held 7,800 people, with permanent seating only on the west end, the rest temporary seating.

No military weapons were spotted. Later came Pat Summit, her string of women’s teams NCAA championships and 21,678-seat Thompson-Boling Arena.

The Volunteer fans were rowdy and obnoxious — some things never change. The cheerleaders were beautiful. But what I remember most was a quiet walk along the Tennessee River the night before the game, an escape from our hotel, a pleasant, memorable, educational journey from the Midwest cornfields, the first of many such journeys.

I have no idea who won that game.

The studs of Vanderbilt and Creighton

Vanderbilt, another of those academic schools, had a unique raised floor built above the seats like a stage in its Memorial Gymnasium. The players were thus seated at the ends of the floor against a wall at least they fall backwards into the crowd when agitated.

Its stud was Clyde Lee, a later NBA star who averaged 21.4 points and 15.5 rebounds over his college career, with 41 points against Kentucky. Vanderbilt still uses that gym — greatly expanded and the oldest in the SEC.

We also along the way played Brigham Young University in Provo Utah. I had never seen a snow-covered mountains until we got up in the morning and pulled back the motel curtains.

I can still see them. I have no idea who won that game, either.

We played Creighton in Omaha and got wiped out, holding Paul Silas to about 33 points and 27 rebounds. Big loss, but fun to watch him with the Celtics.

We played Tulane in New Orleans and after being warned in a pre-game meeting to get to bed early we met a coach about midnight on Bourbon Street.

Moving over to the old Southwest Conference in the early 1960s, Baylor played its games in the Waco “Heart O’ Texas Fair Complex” — abbreviated H.O.T. With an attached livestock barn.

That complex also hosted a rodeo, livestock shows, Elvis and Slim Pickens.

Our locker room, as might you expect in a building with an attached livestock barn, was almost adequate for its purpose. This was no Freedom Hall. As with LSU, a noticeable deposit of outside dust could be found on the rodeo playing floor, with the spectator stands some distance back in dim light.

The Bears — men and women — now compete in the Big 12 Conference in the 10,284-seat Meyer Arena. The women were 2019 NCAA champions — two years before the men won it all — and both remain highly ranked. No one would have believed it in 1961.

We flew to the University of Arkansas in a 1940s propeller driven, DC3 which could cruise at a breathtaking 217 miles an hour. In retrospect, the DC3s were the big yellow school buses of the day.

The planes belonged to Trans-Texas Airlines, which the long-legged lanky folk who boarded them commissioned “Tree Top Airlines.” We would stuff the plane with players, coaches, a trainer, luggage, basketball and a couple of pilots. I don’t remember any flight attendants.

The small airport outside Fayetteville Arkansas was in a low valley in the Ozark Hills. The memory of that trip is looking out the window as the treetops sailed past below us, and then, above us.

We played the Razorbacks in Arkansas Fieldhouse. On occasion, the fans would stand and cheer “Wooooooo Pig Sooie,” which made no grammatical or audio sense, even to an Illinois farm country type. At one point this season Arkansas basketball was ranked 10th in the nation.

Playing hoops in Texas

Texas Tech, located in Lubbock about 500 miles northwest of Houston and still somehow in Texas, was another DC3 trip. The West Texas scenery was mostly open, flat and barren, but still somehow beautiful. Even the salt licks had some exotic appeal. Plus Lubbock was the home of Buddy Holly.

Texas Tech is now also in the very competitive Big 12, and continually ranked nationally in the top 20 and trending up. Even Bobby Knight wandered out there. And Tubby Smith.

Its early 1960s teams were among the best in the old Southwest Conference, drawing about 8,000 noisy fans a game, more than the population of about 95 percent of West Texas towns.

My most remembered Texas Tech opponent is Mac Percival, who never played a down of college football, taught high school four years after college and then became a kicker for the Chicago Bears.

We played Texas (occasionally now ranked in Top 25) in Gregory Field House, a tight-fitting, 4,000-seat gym with balconies and a floor where the fans sat so close they could kick you with their boots. The Texas women play there now.

For all that, and the occasional two-fingered “Hook em’ Horns,” it was a good place to play. It had a Hoosier or Kentucky basketball look and feel.

There was no rodeo dirt. Two of our senior players were from Austin and one of them, following a narrow and noisy defeat, left the arena with one middle finger raised, half the number required for a “Hook em’ Horns.”

At the often now-ranked Texas A&M in College Station, the cadets would wear their uniforms to the games and rock back and forth in alternative rows creating a mad, dizzying motion that made free-throw shooting, if not just plain shooting, a little difficult. A near fistfight broke out on our exit. Don’t remember who won that, either.

The only thing I remember about playing TCU — also now figuring in the top 30 ratings — is that the night we were supposed to play SMU in Dallas the cab driver took us to the TCU gym in Fort Worth, also lovingly referred to as “Cowtown.” He must not have been a basketball fan.

SMU in Dallas did get to the Final Four in 1956, losing to a San Francisco team with two guys named Bill Russell and Sam Jones. We last played SMU in January 1964, maybe six weeks after President Kennedy was assassinated.

All I remember about that game is walking from our hotel over to Dealey Plaza and looking up at the sixth floor of the Texas Book Depository.

Bob Hill is a happily retired Courier Journal columnist and ardent gardener who owned and operated Hidden Hill Nursery and Sculpture Garden in Utica, Indiana, with his wife, Janet, for 19 years.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: What it was like playing SEC, Southwest Conf. basketball in the '60s