- "When it stops hurtin', it'll be all right."

- — Trout Fishing in America, "Safe House"

One afternoon in 1982, in the downtown YMCA in Shreveport, Ezra Idlet must have felt magic in his hands.

One, two, three, four, five — maybe six — rainbow parabolas launched from various spots between 23 and 28 feet away from a 10-foot-high basket settled gently into a net hung from an untouched metal hoop. One of the game's regulars, a small forward who'd lettered at Captain Shreve a dozen years before, asked in astonished exasperation:

"Who are you? Larry Bird?"

"Nah, I'm his sister," the long-haired, earringed, 6-foot, 9-inch Idlet drily replied.

I was a witness to this exchange. I might have even assisted on a couple of those long-range jumpers.

Ezra was something like a rock star. I knew all about Trout Fishing in America, the folk rock duo he'd played in with Keith Grimwood, which I assumed was named after Richard Brautigan's surreal 1967 novella, which was being passed around a lot in would-be bohemian circles in those days.

Trout Fishing was already an institution, I thought, though checking my memory against the facts, they had apparently only released one full-length album, "You Bore Me to Death!" by that time.

I knew the origin myth of Trout Fishing. When he was at Lamar High School — the "snooty" public high school in Houston that counts Nobel Prize winner Robert Woodrow Wilson, novelist James Lee Burke, newscaster Linda Ellerbee, and actors Jaclyn Smith and Paula Prentiss among its alumni — Idlet formed a country rock/folk band called Wheatfield with classmates Craig Calvert and Connie Mims.

In 1972, Idlet — who'd been recruited by a number of Texas schools — played basketball for the McLennan Community College Highlanders in Waco. It was a good team — undefeated at home — but Idlet spent a lot of nights playing solo shows at Poppa Rollo's Pizza, and Wheatfield seemed like a viable career choice. So he chose music and never held any other sort of job. (Though if he'd always shot as well as he did that afternoon at the Shreveport Y ...)

In 1974, Wheatfield added a bassist, and soon after that a percussionist drummer. They played parties at the University of Houston and Rice University, and appeared on local TV as well as the inaugural season of "Austin City Limits."

NAME, BAND CHANGES

In 1976, they got a cease and desist letter from Oregon that claimed another band owned the name. At the time they were working with choreographer James Clouser, scoring the rock ballet "Caliban," based on Shakespeare's "The Tempest." So they took the name St. Elmo's Fire, seen as a harbinger of the storm central to the play.

That year, the classically trained Grimwood, who attended the University of Houston and played string bass in the Houston Symphony Orchestra, joined the band after a union lockout. He thought he'd eventually go back to the symphony.

St. Elmo's Fire toured Colorado and played across Texas. They scored another rock ballet for Clouser, "Rasputin." They never got a major label record deal, though they came tantalizingly close. They disbanded in 1979.

Idlet and Grimwood struck out as a duo. Grimwood came up with the Trout Fishing in America name because he liked the book and the response to it when people asked him what the band was called. Some people got it; others just thought it was weird, but it worked.

And they worked, pretty much constantly, for about 40 years. They were sort of an Americana analog to They Might Be Giants, the absurdist modern rock band that has as its core the duo of John Flansburgh and John Linnell.

Both They Might Be Giants and Trout Fishing in America made songs that explored the world from the perspective of a curious naif; both had lyrics seemingly written from a children's perspective. But there was a quality of unironic warmth in Trout Fishing in America's work that was missing from the angular, sometimes dissonant work of Flansburgh and Linnell.

And so Trout Fishing in America could genuinely appeal to kids.

Whether that's what they meant to do in the beginning may be beside the point; teachers who came to their shows recognized the quality, and soon Trout Fishing in America was operating parallel careers — they were both a children's' act and a duo that appealed to adult audiences.

As Grimwood and Idlet grew up — as they got married and acquired children of their own (along with mortgages and other accoutrements of adulthood), their songwriting evolved. It was always about what was going on in their lives, generally low-drama dad rock.

When they played for kids, they juggled and incorporated bits of physical humor. It helped that just by appearing onstage together they could bemuse — Grimwood, at 5-foot-5, was shorter than some of the standup basses he played. And he was standing next to Larry Bird's sister.

They carved out a unique space in the culture. They long ago stopped chasing conventional commercial success to make their own way. They were among the first musicians who formed their own record label and marketed their music themselves.

In the early '90s they moved from Houston to northwest Arkansas — Grimwood to West Fork, Idlet to somewhere near Prairie Grove.

They kept putting out records and playing shows. They picked up Grammy nominations, National Indie Awards, multiple Parent's Choice and NAPPA Gold (National Parenting Product) awards, and an American Library Award. They had fans who thought of them as family. And they had the family thing too. It looked like they could go on forever. As it was, it was only about 40 years.

Then, like everything else, Trout Fishing in America was stopped by covid-19.

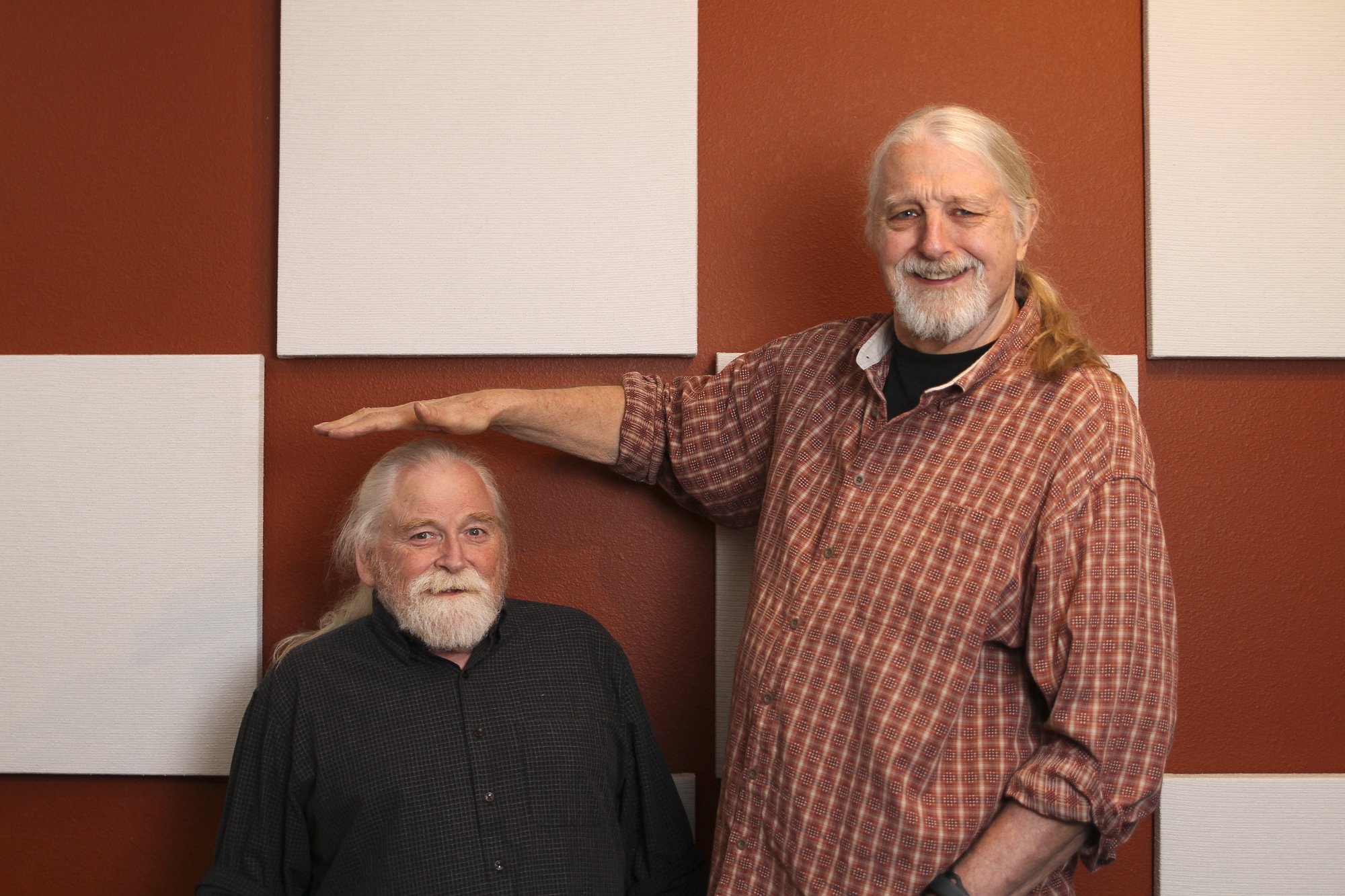

Keith Grimwood and Ezra Idlet of Trout Fishing in America perform a show for kids in 2015 at the Fayetteville Public Library. (Democrat-Gazette file photo) 'SAFE HOUSE'

Keith Grimwood and Ezra Idlet of Trout Fishing in America perform a show for kids in 2015 at the Fayetteville Public Library. (Democrat-Gazette file photo) 'SAFE HOUSE'

"Safe House," their 25th album, is very much a response to the pandemic. Like all musicians, Grimwood and Idlet had to figure things out. They were in Pennsylvania at a show when they found out. They played, packed up and drove to their respective homes. They didn't see each other for more than a month, the longest in more than 40 years.

That wouldn't work. They decided to bring their families together in a pandemic pod. They decided to be together, to play music, to livestream shows, to write and record. To explore their instruments and some new songs as well. They set up a streaming studio in Idlet's recording studio.

Mostly, they wrote.

"Safe House" is in some ways a modest record, the product of two highly professional musicians of uncommon intelligence who know how to underplay certain elements and to lean into their strengths. There's gentle humor where others might reach for outrage, and great confidence in their voices. (Idlet and Grimwood tend to trade off on lead vocals, and their harmonies have an agreeable gruffness that fits beautifully in their relatively unfussy arrangements.)

You can clearly hear each instrument; Grimwood's bass and Idlet's guitars (he also plays a touch of mandolin and light percussion) each fall into their own space. (There's only one outside musician featured on the album: Adam Collins of bluegrass band Arkansauce plays vibraphone on "Oh, Those Afternoons.")

But you can hear a certain poignancy in the lyrics, a kind of plaint in the Grimwood-sung title track and album opener: It's just so hard to keep it all inside/It'll be alright. When it stops hurting, it'll be alright.

The song could be construed literally, as about a physical space, a shelter against a storm. But a shelter can also be a prison, and locked-in syndrome is something a lot of us have at least tasted in these past couple of years. Then Idlet answers with bouncy "Knock Me Down," one of those inevitable songs that immediately feels like it's been around forever. Of course, he's going to get right back up again.

Idlet's guitar work shines on "Don't Be Callin'." There's an excellent re-imagined cover of Susan Werner's "Barb Wire Boys"; a very funny yet probably journalistically accurate road account, "We'll Always Have Ardmore"; and a bluegrass workout in "Where's That Dog Gone Now?"

Those are just the immediate highlights; "We Have Not Arrived" sounds like an anthem that might have been pulled from a Broadway show, maybe a collaboration between Lin Manuel-Miranda and Paul Simon in his underrated "Capeman" period. And "Looking at a Rainbow," with its refrain reminding us that if we see colors in the sky the storm must have passed, is an appropriately hopeful album closer.

Keith Grimwood and Ezra Idlet have forged a four-decade career under the name Trout Fishing in America. “Safe House,” their 25th album, is a response to the pandemic. BEST SERVED LIVE

Keith Grimwood and Ezra Idlet have forged a four-decade career under the name Trout Fishing in America. “Safe House,” their 25th album, is a response to the pandemic. BEST SERVED LIVE

Trout Fishing in America has never been considered an album-producing machine; they are live musicians whose highest and best use is as stage performers receiving and reflecting the energy of an audience. The recorded versions of their songs are just that: versions. For the definitive experience? You have to be there.

In the room, as the man says.

But we've been prevented from being in a lot of rooms with other people these past months, and now that we are just beginning to venture out, there's still trepidation and free-floating anxiety. Trout Fishing in America is going out on the road again; you should check your local listings and their website — troutmusic.com — for schedules and merchandise and such. (They've got a lot of CDs and downloads and videos.)

One of the worst things that happened to our culture sometime in the second half of the last century was that the word "nice" somehow acquired a pejorative connotation, as though "nice" is not a good thing to be, or somehow the least desirable good thing.

It's a pity, because the perfect way to describe this duo is as a couple of nice, talented guys pursuing the good life through the application of their particular skills to the making of art. It's a good way to live, and a good model for people to follow. There's a lot of joy in this music. And peace. And decency.

They're the kind of teachers kids deserve, and the sort of artists to whom we all ought to pay attention.

Maybe it's fair to appraise the totality of their careers.

Hey guys, nice shot.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com