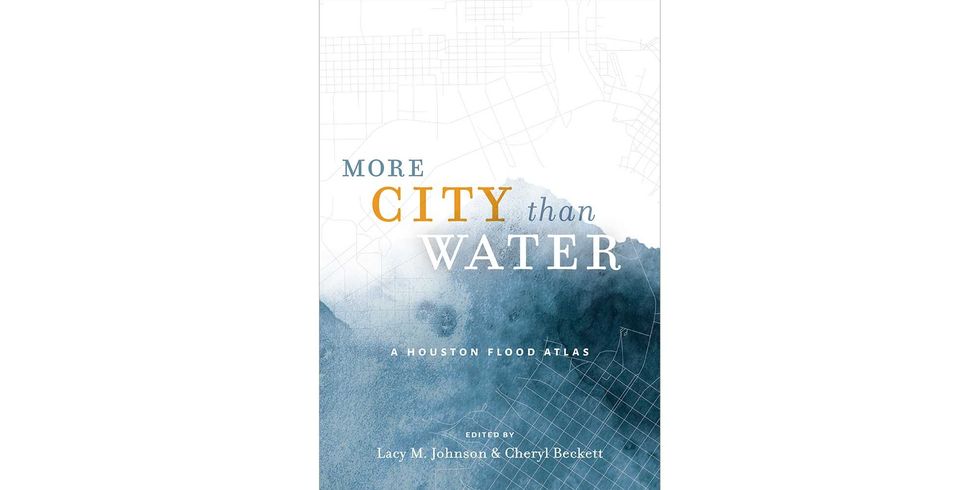

When is a book an act of advocacy? It’s a question I keep asking in regard to More City Than Water: A Houston Flood Atlas, which takes as its entry point the devastating flooding caused by Hurricane Harvey in late August 2017. Edited by Lacy M. Johnson and Cheryl Beckett, More City Than Water—the title, Johnson explains, “comes from a photograph of a sign I saw in the days after the storm: ‘More Love Than Water’ it read, meant to signify that however much water surrounded us, we were surrounded by even more love”—makes for a sort of deconstructed love story, in the form of 22 essays, interviews, and bits of testimony, each accompanied by its own vivid and impressionistic map.

The result is beautiful, moving, and, most fundamentally, provocative—a collective portrait of a city defined for good and ill by its relationship to water. As Sonia Hamer writes in her essay “Gusher”: “The storm illuminated the city’s interconnectedness, shined a spotlight on the way we all link together in a diffuse, delicate web. What happens in one part of the city has repercussions elsewhere. When rain falls in the west, it flows downstream, out of the bayous and the drainage ditches, into the streets, rushing and rushing until, eventually, it reaches the sea.”

Johnson and Beckett divide More City Than Water into three sections: “History,” “Memory,” and “Community.” But what makes the book essential are its overlaps. History, memory, and community, after all, are always in conversation with one another. They are impossible to pry apart. Such an idea is encoded not only in the structure of this “atlas,” but also in the conversation it seeks to activate. How are we to understand the present without knowing how we got here? How are we to imagine where we are going without recognizing where we’ve been?

“Flooding,” Aimee VonBokel affirms in “History Displaced,” which explores the history (water and otherwise) of Independence Heights, which she identifies as “the first Black municipality in Texas,” “may seem like an engineering problem—or a challenge we should hand over to water experts. But in this case, it’s a problem with social, political and racial dimensions.”

What VonBokel is addressing is inequity, why some communities suffer more than others do. “The cycle goes like this,” she continues: “Black families buy land and build a community. Their community is surrounded by incinerators or polluting industrial sites (as happened in Pleasantville and Houston’s Fifth Ward, where a cancer cluster has been identified). Or their community is flooded (as in Independence Heights). Or a highway comes through and rips apart the social and economic fabric (which is what happened to Freedman’s Town, also known as Houston’s Fourth Ward).”

You don’t have to be familiar with the neighborhoods to recognize the conditions. We find the equivalent in every city: South Los Angeles, effectively walled off by freeways, or San Francisco’s Bayview Hunters Point, with its shipyards and contamination sites.

“Not all neighborhoods,” Allyn West observes in “The City That Saved Itself,” “experience disasters the same way.”

For anyone who’s experienced a disaster, there’s no doubt West is right. Yet even now, this has not enough effect on policy. That’s one of the points of More City Than Water, and one of its objectives: to encourage us to think kaleidoscopically. In part, this has to do with the editors. Johnson is a memoirist and essayist who teaches nonfiction writing at Rice University, while Beckett is a graphic designer and an associate professor at the University of Houston School of Art. The book is a project of the Houston Flood Museum, which Johnson founded in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey “to act as a catalyst for reimagining the ways in which Houston, the Gulf Coast, and the wider world evolve in a context of persistent natural disasters.” The maps were produced by Beckett’s senior graphic design students. Together, they have put together an atlas that is groundbreaking—not only in its presentation (although that too), but also in its refusal to color within the lines.

What I mean is that, for Johnson and Beckett, the intention is to take the broadest view. This leads them to what epidemiologist P. Grace Tee Lewis calls environmental justice, which asks us to consider “how we can equitably distribute or share the burden of the industrial development and growth that is needed to maintain a strong economy.” I’m drawn to thinking like this because it requires responses that are pragmatic as well as idealistic; indeed, it insists that idealism is the most pragmatic course. How do we take care of everyone? Such a question echoes through these pages like the beating of a heart.

If everything is connected, we are all in it together. If everything is connected, no one is exempt. High ground can flood as readily as low, which happened during Harvey. Ice melt in Greenland can cause a deluge in the Gulf. In such a context, water becomes a living thing—necessary for our survival, yes, but also an entity unto itself.

“I really think that water bodies are living in a very real way,” the Sierra Club’s Alex Ortiz tells Johnson in one of the book’s interviews. “The ecosystem is very much alive. It is home and habitat for a lot of different wildlife. It serves such an important function for us, too. I think being mindful and respectful of this very valuable resource that we have is important. It’s our responsibility to be good stewards.”

A flood, in other words, is not just something that happens. Instead, it grows out of a series of antecedents. Some are historical, or geographical. Others are social, economic, and political. All of them are our responsibility. All of them have to do with us.

And yet, how do we make sense of these complexities? How do we come to terms with such a reckoning? In her astonishing essay “Lean to That Flood Song,” Laura August teases out the nuances, pondering futility and protest, the balance between stasis and change. “Assume that human action, the form of protest, or organizational style has no significant impact on whether a movement will succeed,” she writes, quoting activist Micah White. “Now what do you do to change the world?” The question is one that all of us are facing, as we live through an environmental crisis state that may have already passed the tipping point. What do we do in such a circumstance? How do we preserve community or hope? Art is one answer. Or better: witness.

“We see the floods coming,” August tells us, “because they have already come.”•